October 14

Sono aperte le iscrizioni per il più grande evento dell'anno di Miro: Canvas 25! Iscriviti subito per assicurarti un posto per il 14 ottobre.

REGISTRATI ORA

NYC or Virtual

Sono aperte le iscrizioni per il più grande evento dell'anno di Miro: Canvas 25! Iscriviti subito per assicurarti un posto per il 14 ottobre.

REGISTRATI ORA

Sono aperte le iscrizioni per il più grande evento dell'anno di Miro: Canvas 25! Iscriviti subito per assicurarti un posto per il 14 ottobre.

REGISTRATI ORA

Sono aperte le iscrizioni per il più grande evento dell'anno di Miro: Canvas 25! Iscriviti subito per assicurarti un posto per il 14 ottobre.

REGISTRATI ORA

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

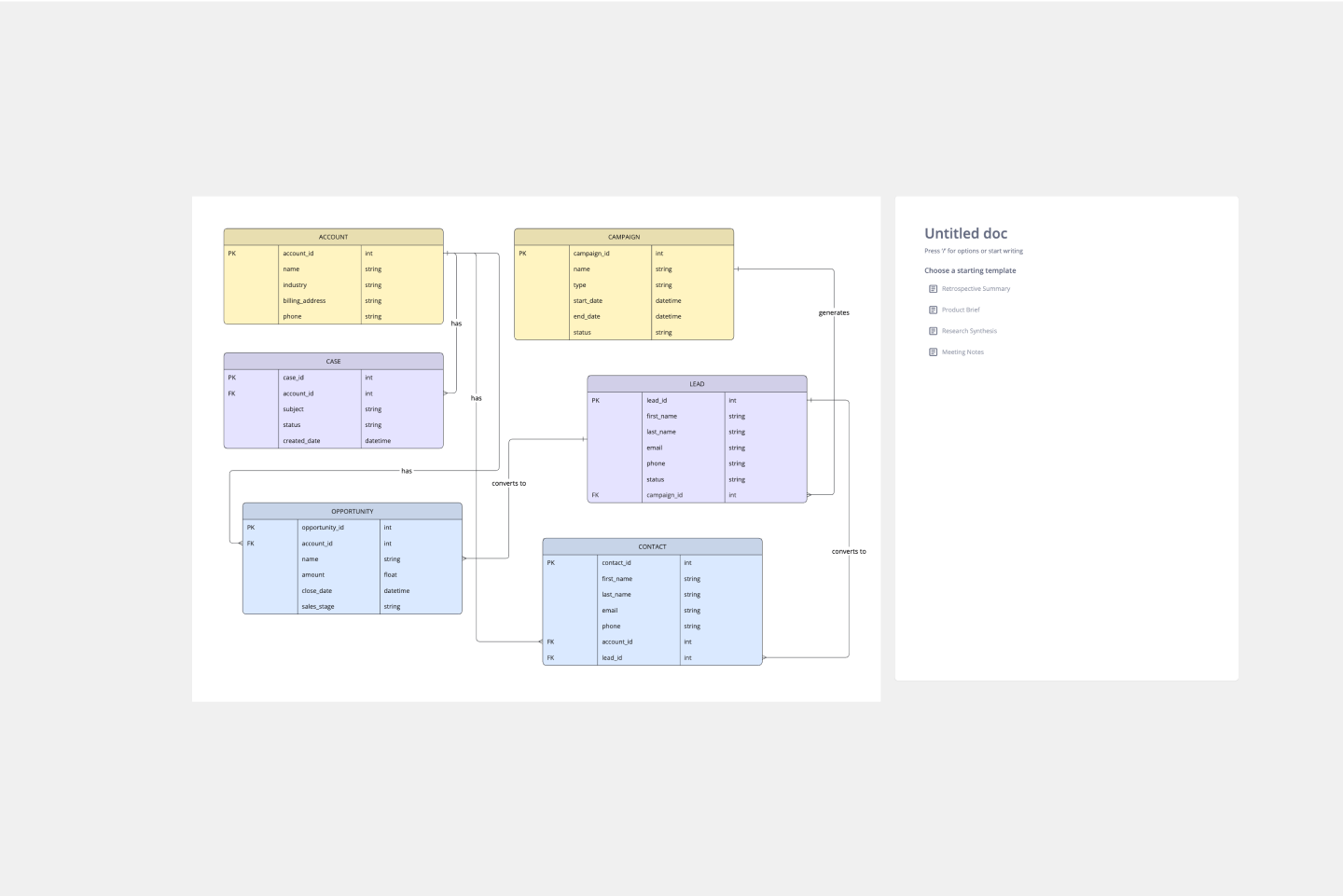

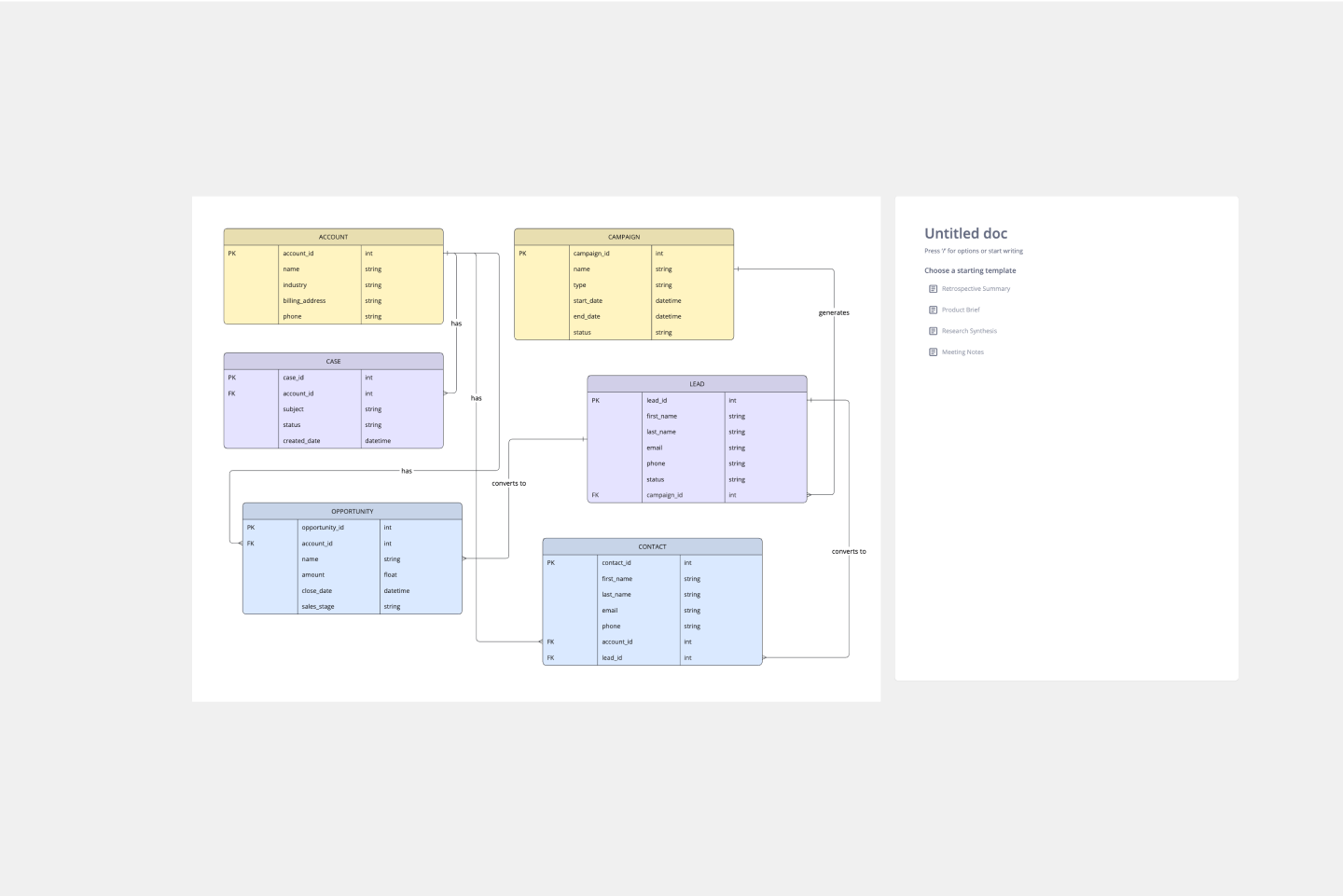

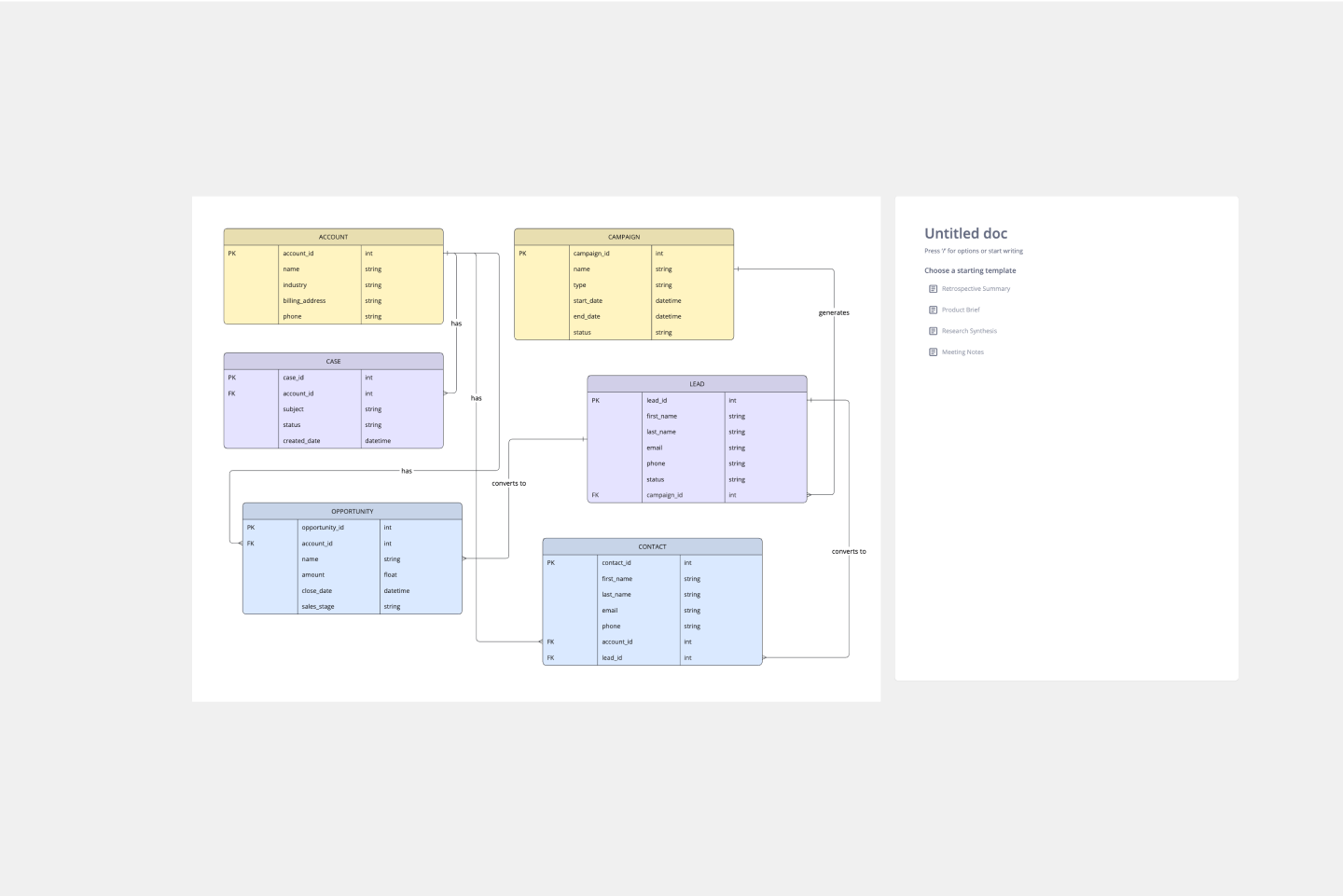

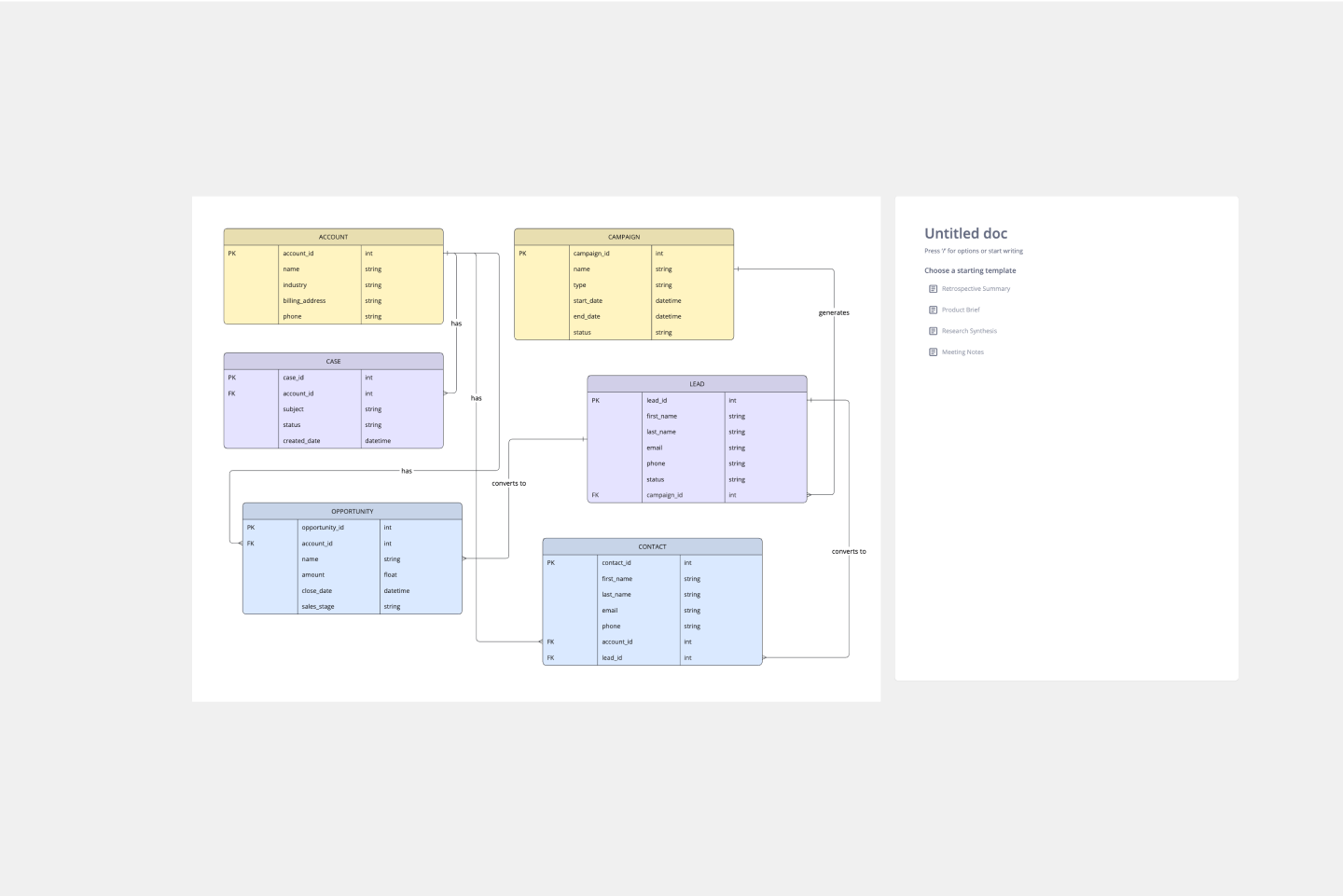

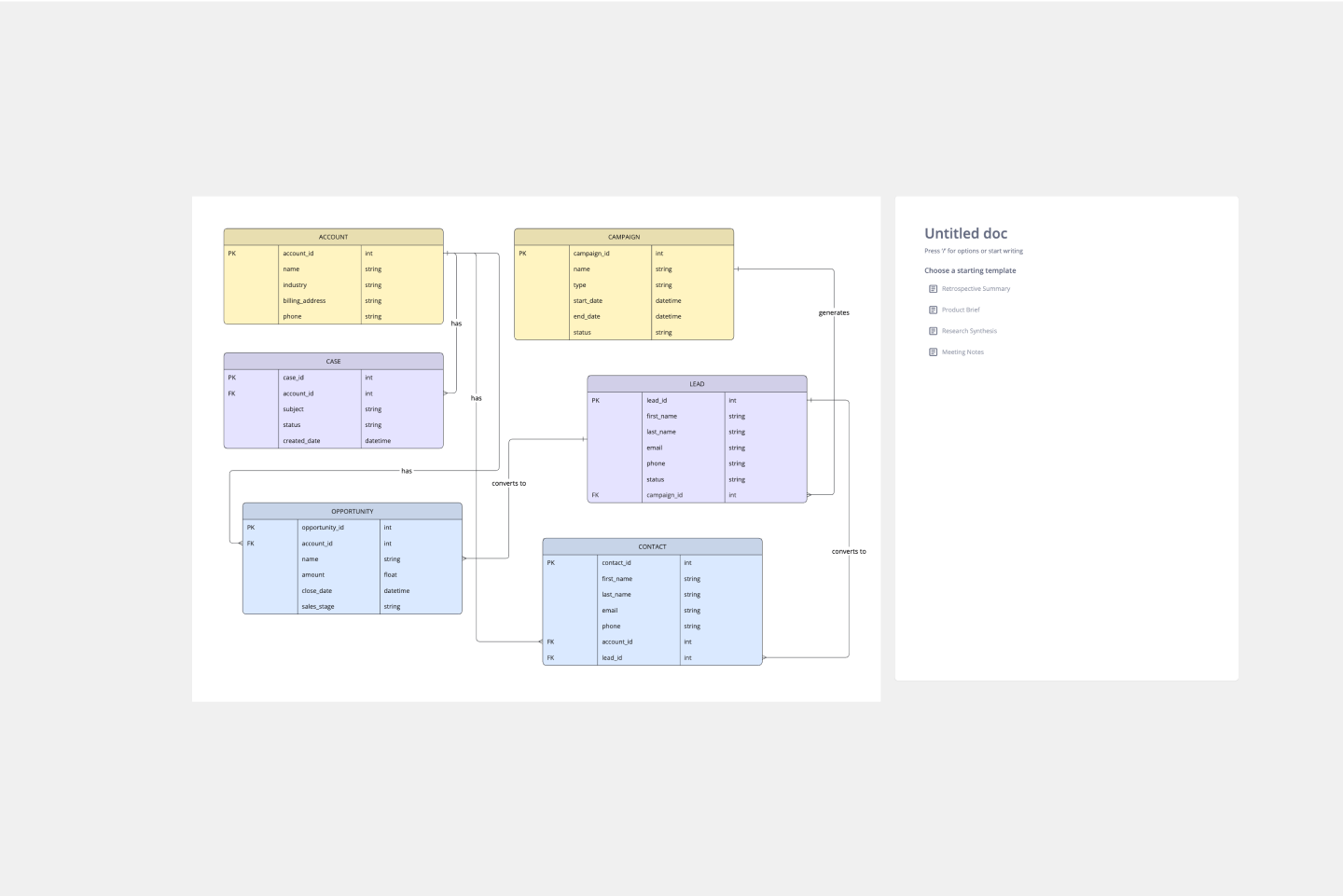

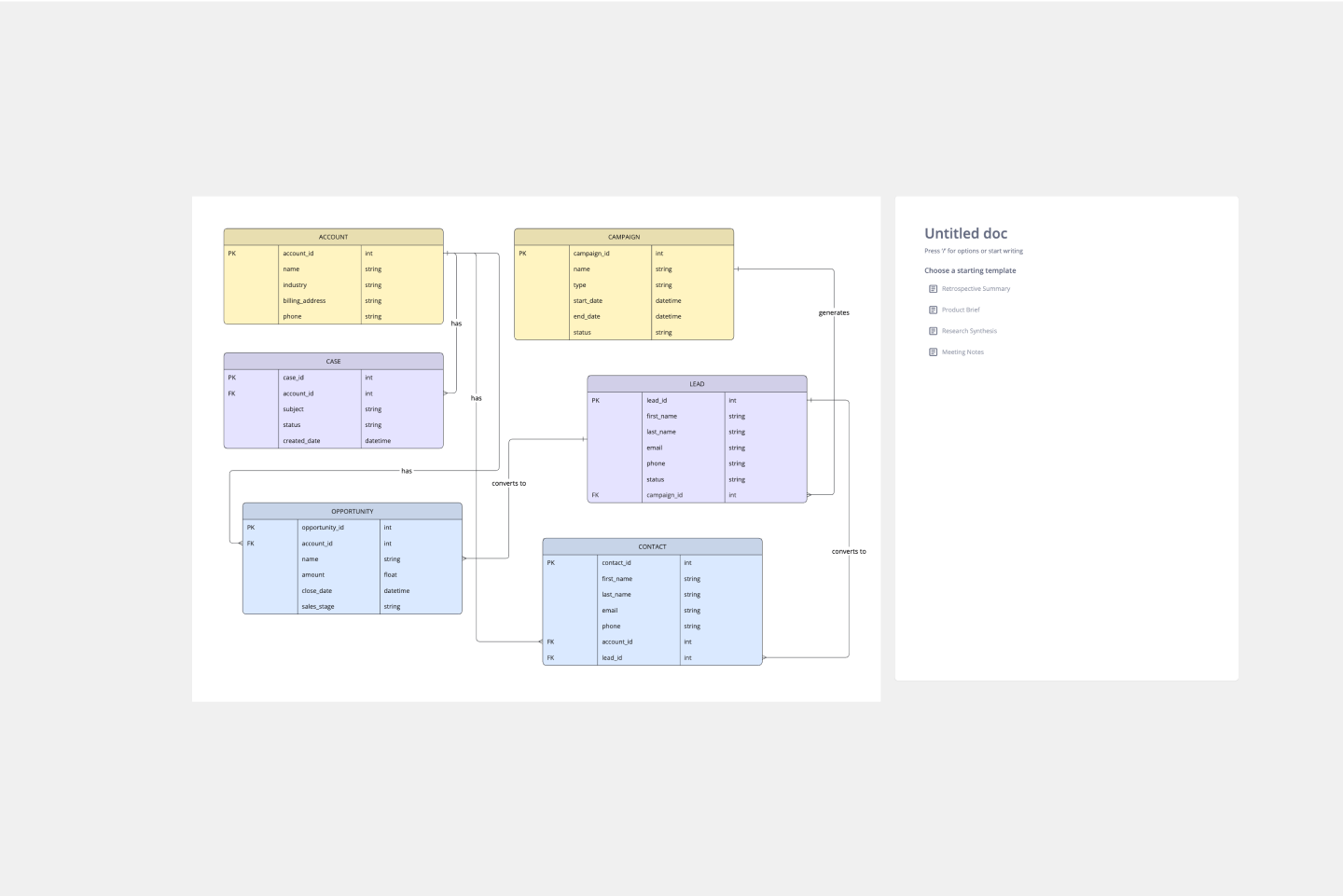

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

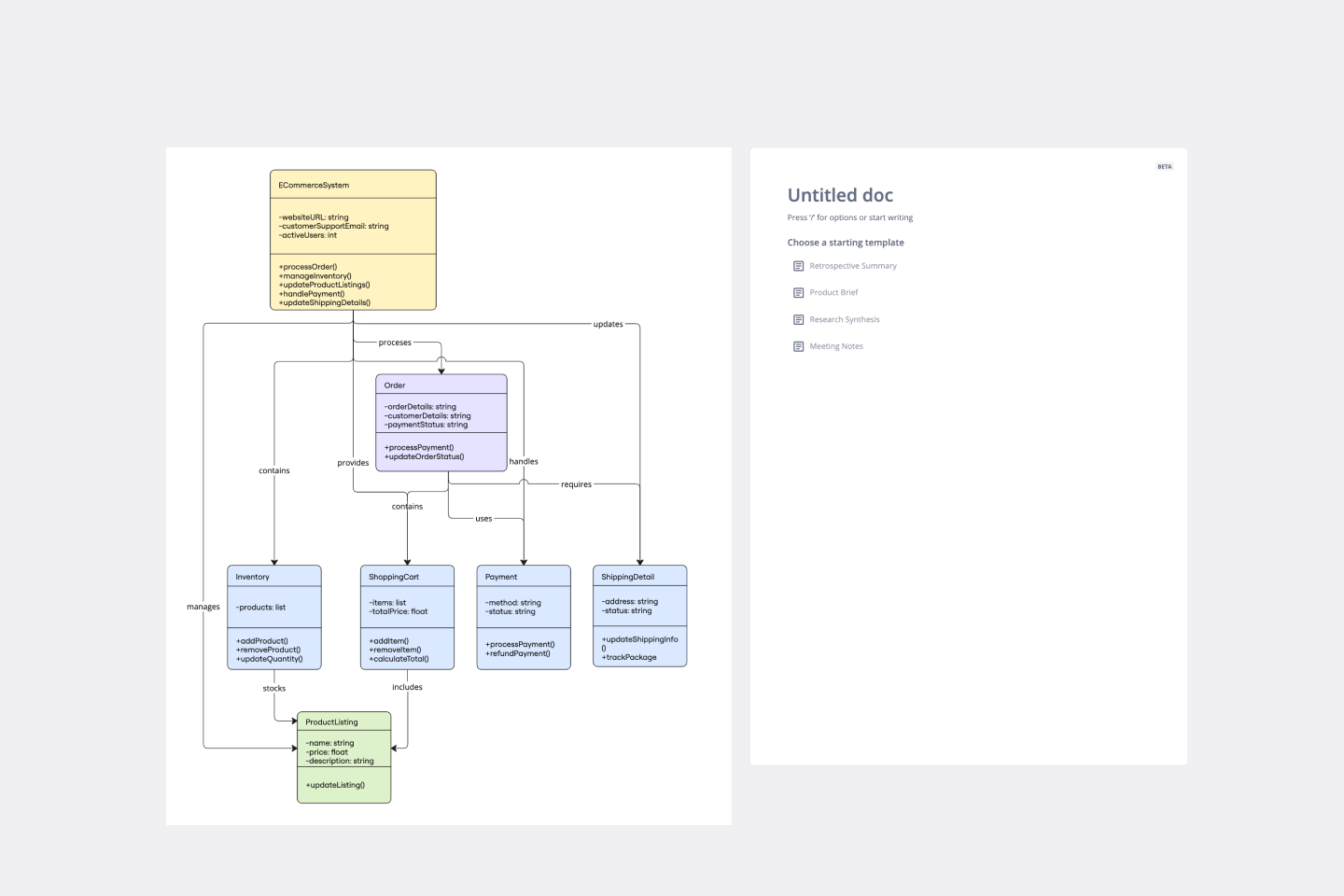

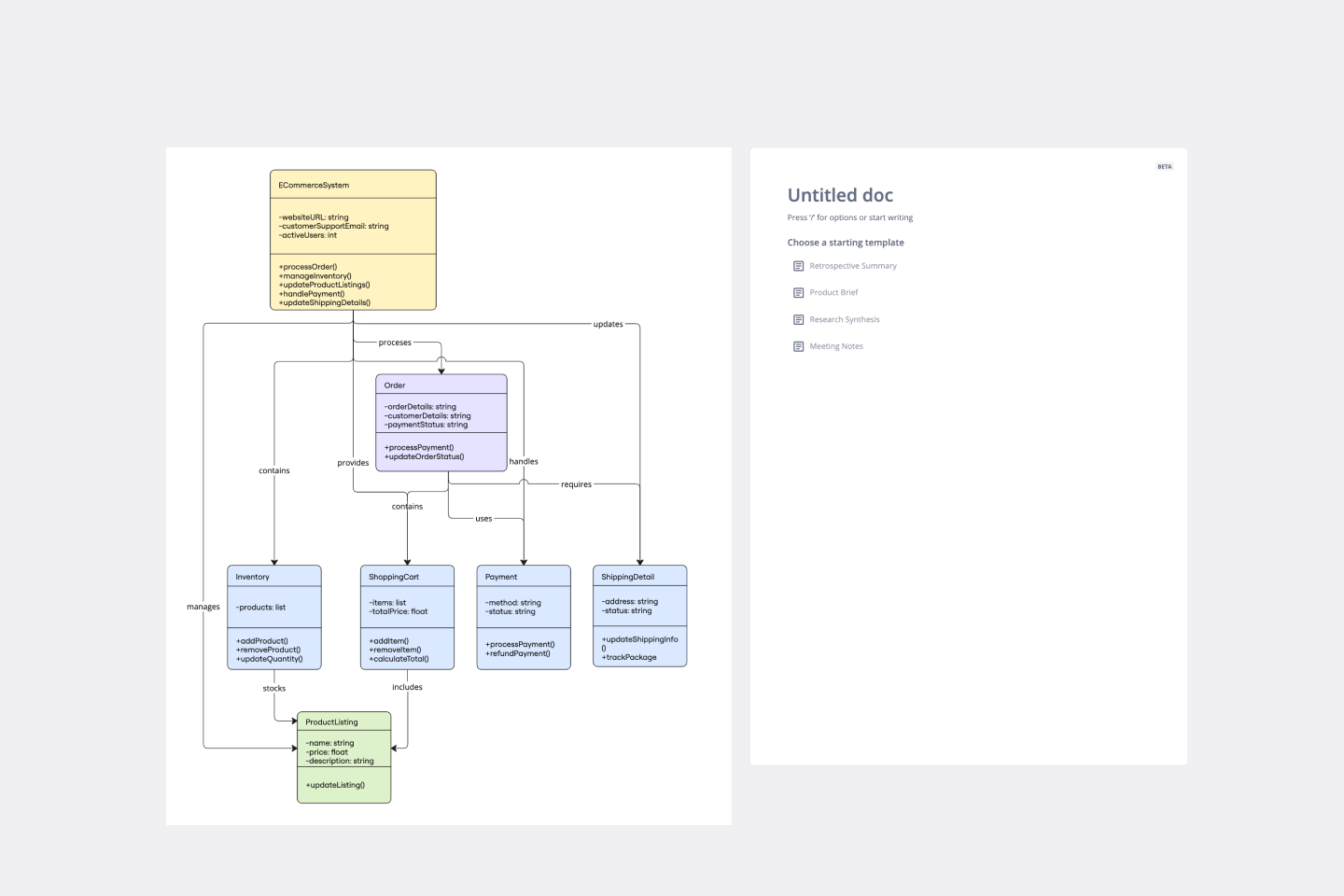

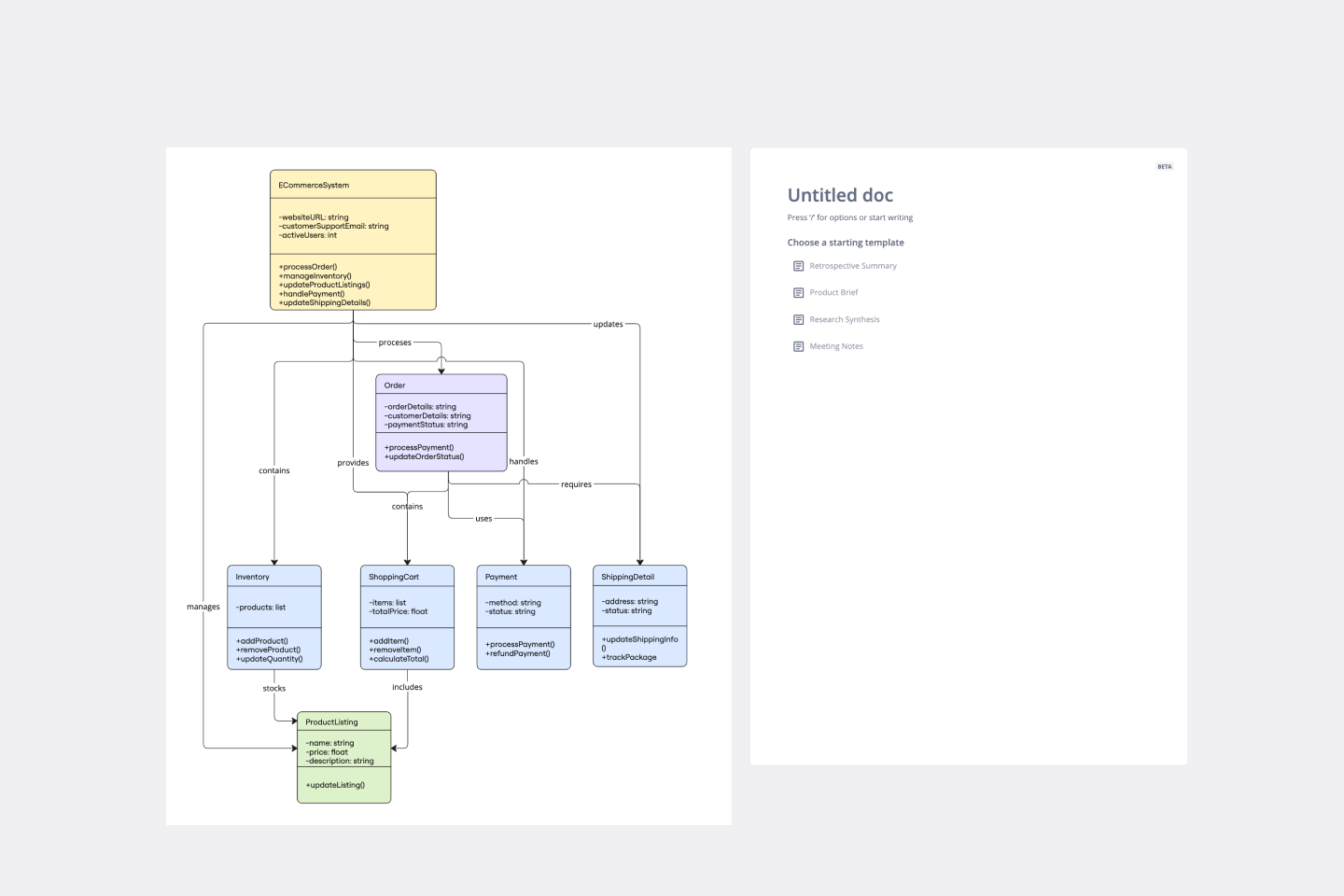

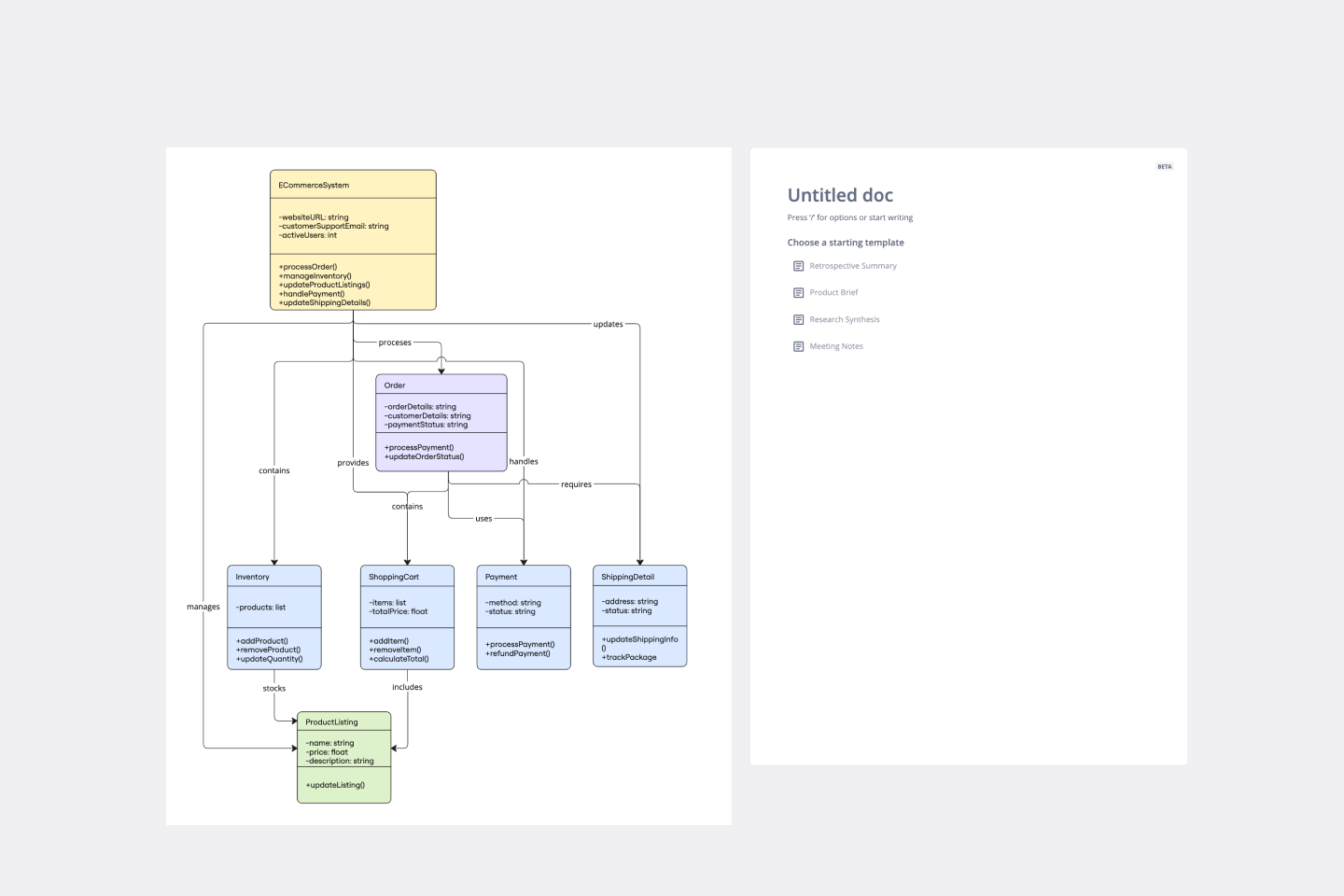

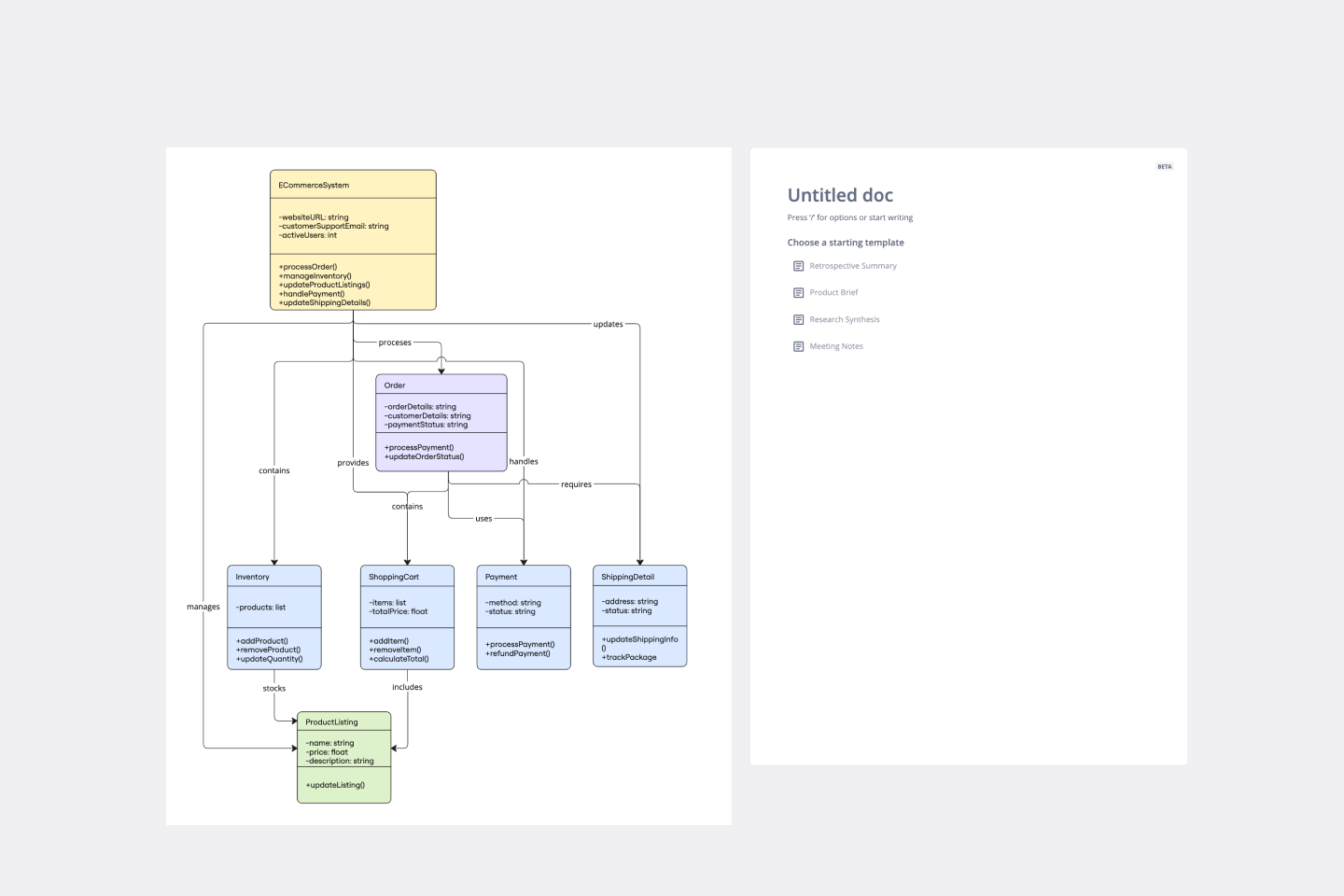

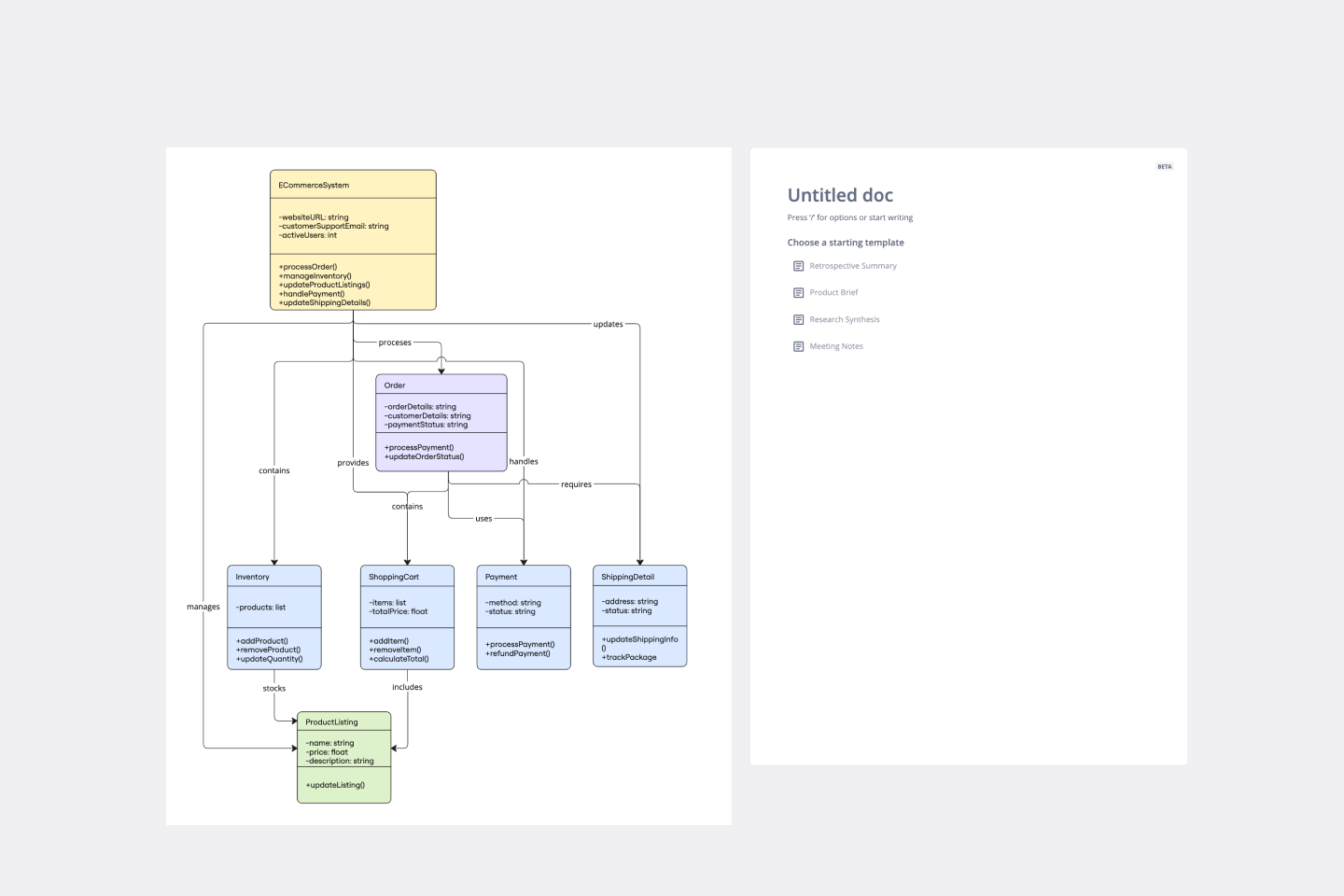

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Visualizza diagrammi, processi e sistemi complessi più velocemente che mai

Con la creazione di diagrammi basata sull'IA puoi passare dal brainstorming alla mappa di processo, dal documento tecnico alla creazione del progetto del sistema in pochi secondi.

Oltre 90 milioni di utenti e 250.000 aziende collaborano nello spazio di lavoro per l’innovazione

Ecco come i team realizzano il prossimo grande successo

Oltre 3000 forme professionali per diagrammi

Risparmia tempo prezioso, usa l’IA per generare diagrammi

Meno fatica, diagrammi migliori

Perché i migliori team scelgono Miro per la creazione di diagrammi

Trasformazione IA

Scopri come l'IA si integra nei tuoi flussi di lavoro attuali realizzandone una mappatura su Miro. Usa il pacchetto forme IA per trascinare e rilasciare le icone IA, definire punti di contatto umani e impostare trigger di automazione.

Mappatura dei processi

Il modo più veloce per mettere in contatto i team, ottimizzare i processi e ampliare la tua attività in un unico spazio di lavoro facile da usare.

Creazione di diagrammi tecnici

Risparmia ore di progettazione manuale del sistema e concentrati su ciò che conta, mantenendo i team allineati su argomenti complessi.

Creazione di diagrammi per l'infrastruttura cloud

Migliora le prestazioni, inizia a ottimizzare i costi del cloud e visualizza la tua architettura, tutto in un unico spazio.

Progettazione organizzativa

Lo strumento più intuitivo per eseguire una mappatura della tua organizzazione e vedere il quadro generale, senza sforzo.

Wireframing

Progetta e itera le interfacce utente in modo collaborativo.

Guarda i diagrammi di Miro in azione

Scopri come i team possono creare, personalizzare e condividere rapidamente diagrammi per essere sempre allineati e agevolare la collaborazione, tutto in un unico spazio di lavoro intuitivo.

Prova i modelli più popolari su misura per il tuo team

Non serve ripartire ogni volta da zero. Esplora l'enorme libreria di modelli personalizzabili di Miro, pensati per le tue attività quotidiane.

Create a clear visual representation of a company's CRM system.

3f38d20a-0abf-4326-8f74-517a432aefc5

Visualizza il flusso dei dati e i modelli di processo con un diagramma di flusso dati.

f2ef89ce-36b3-4f49-ac7c-4a0851041eb8

Crea una guida visiva alla struttura della tua organizzazione.

c8f2189a-946b-40a3-9eff-e2954a3e3920

Il Diagramma dell'architettura AWS è una rappresentazione grafica del framework AWS, inoltre traduce le migliori pratiche quando si utilizza l'architettura Amazon Web Services

8cfe871d-e74a-41cd-b71d-908636d2507e

Deliver a clear visualization of the class structure of an e-commerce system.

5b0855eb-0609-4c1f-8d69-673cf5521888

Chiarisci i ruoli e sostituisci i processi scritti lunghi con riferimenti visivi.

0d701836-612a-46c0-8305-5a55ace59a47

Hai bisogno di aiuto per iniziare?

Accedi a corsi gratuiti per imparare a usare la tela in un batter d'occhio, esplora il nostro blog, ottieni risposte rapide dal Centro assistenza e altro ancora.

Prodotto

Soluzioni

Risorse

Azienda

Piani e prezzi

Prodotto

Soluzioni

Risorse

Azienda

Piani e prezzi

Prodotto

Soluzioni

Risorse

Azienda

Piani e prezzi

Prodotto

Soluzioni

Risorse

Azienda

Piani e prezzi