Et enkelt prosessoversiktsverktøy

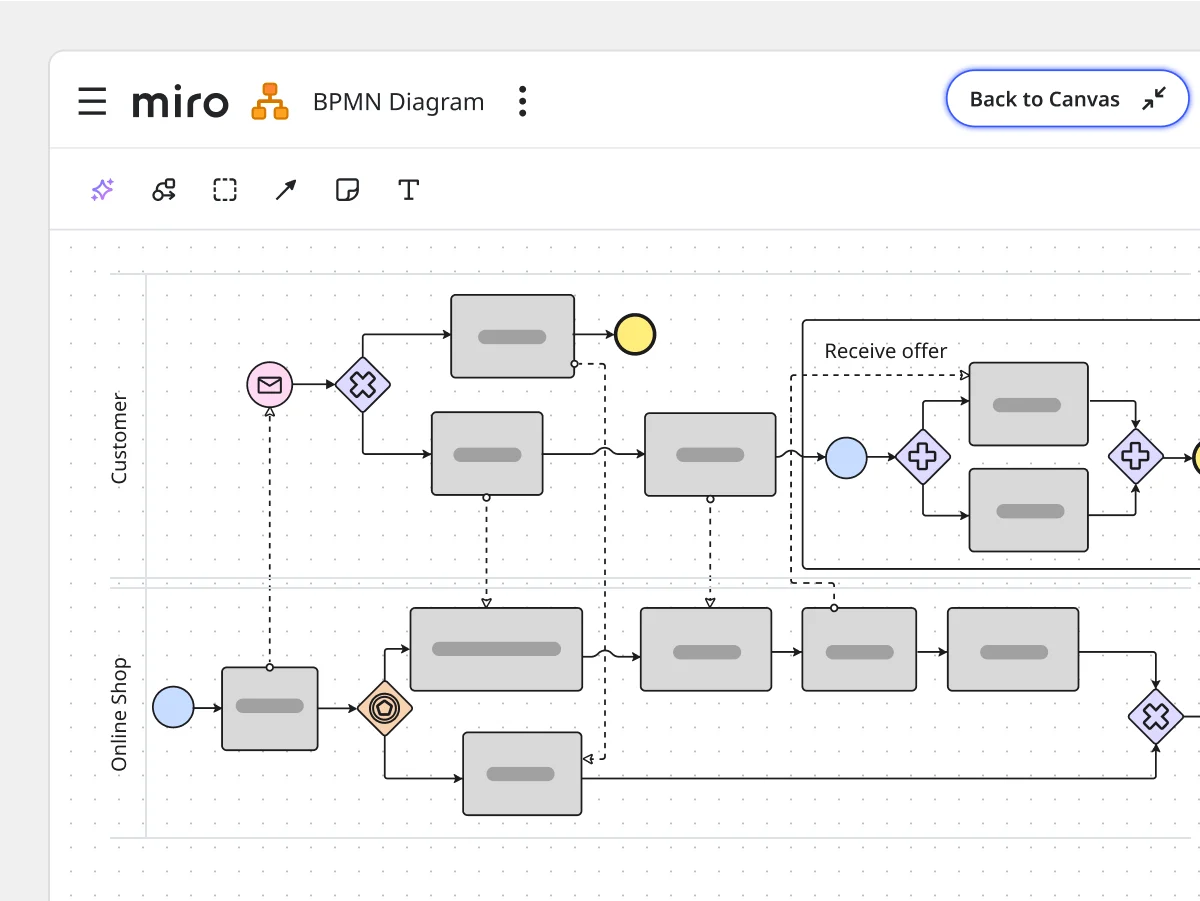

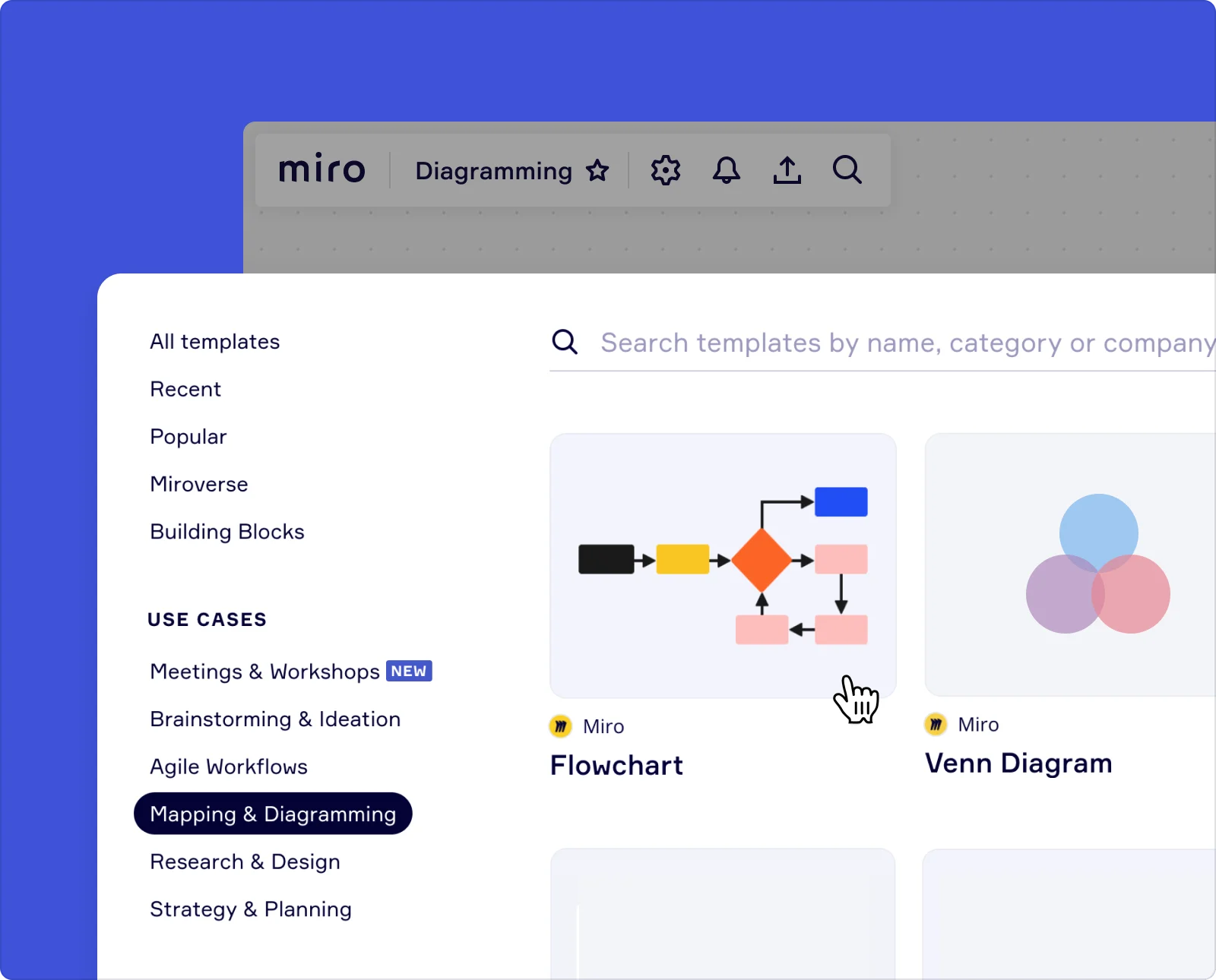

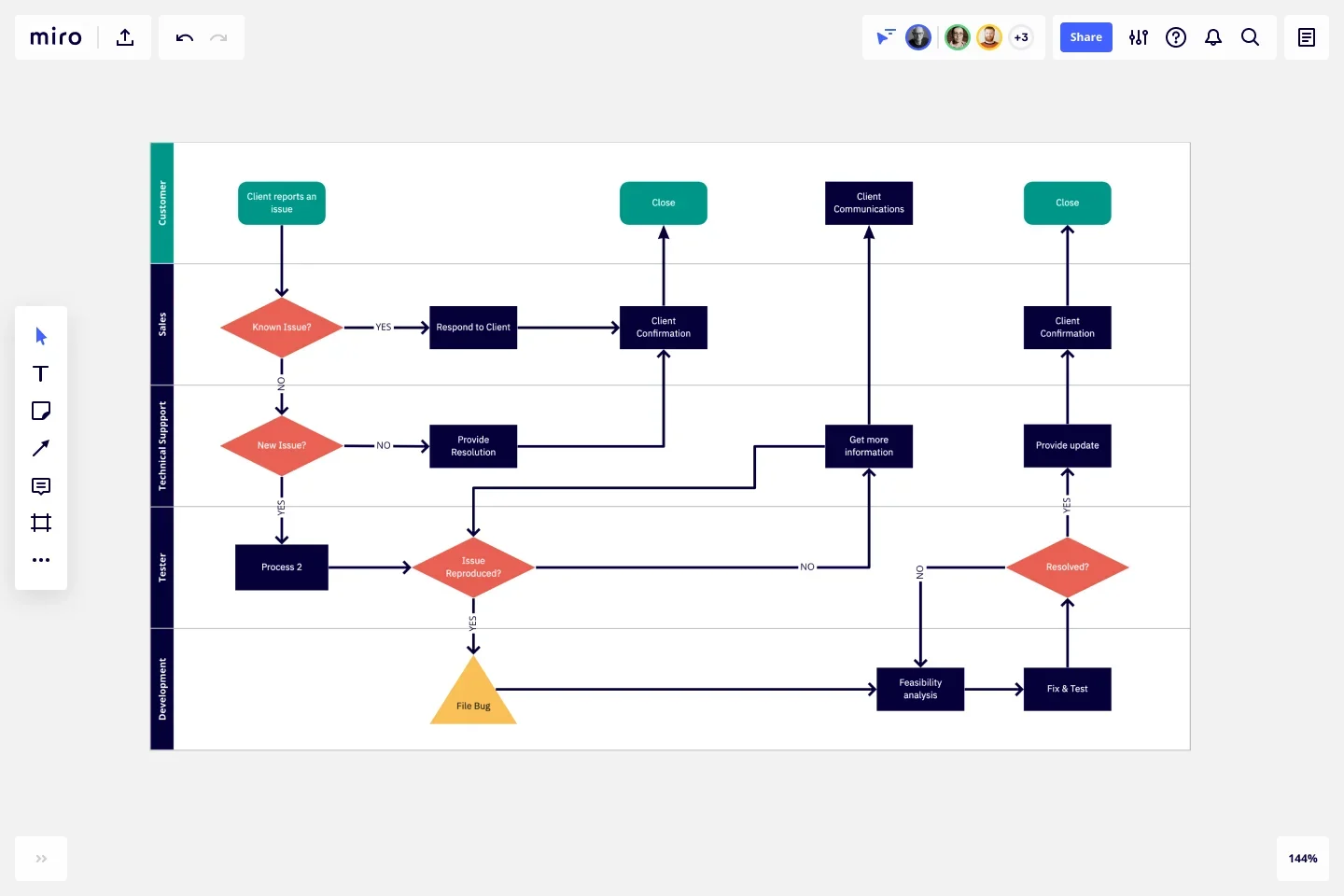

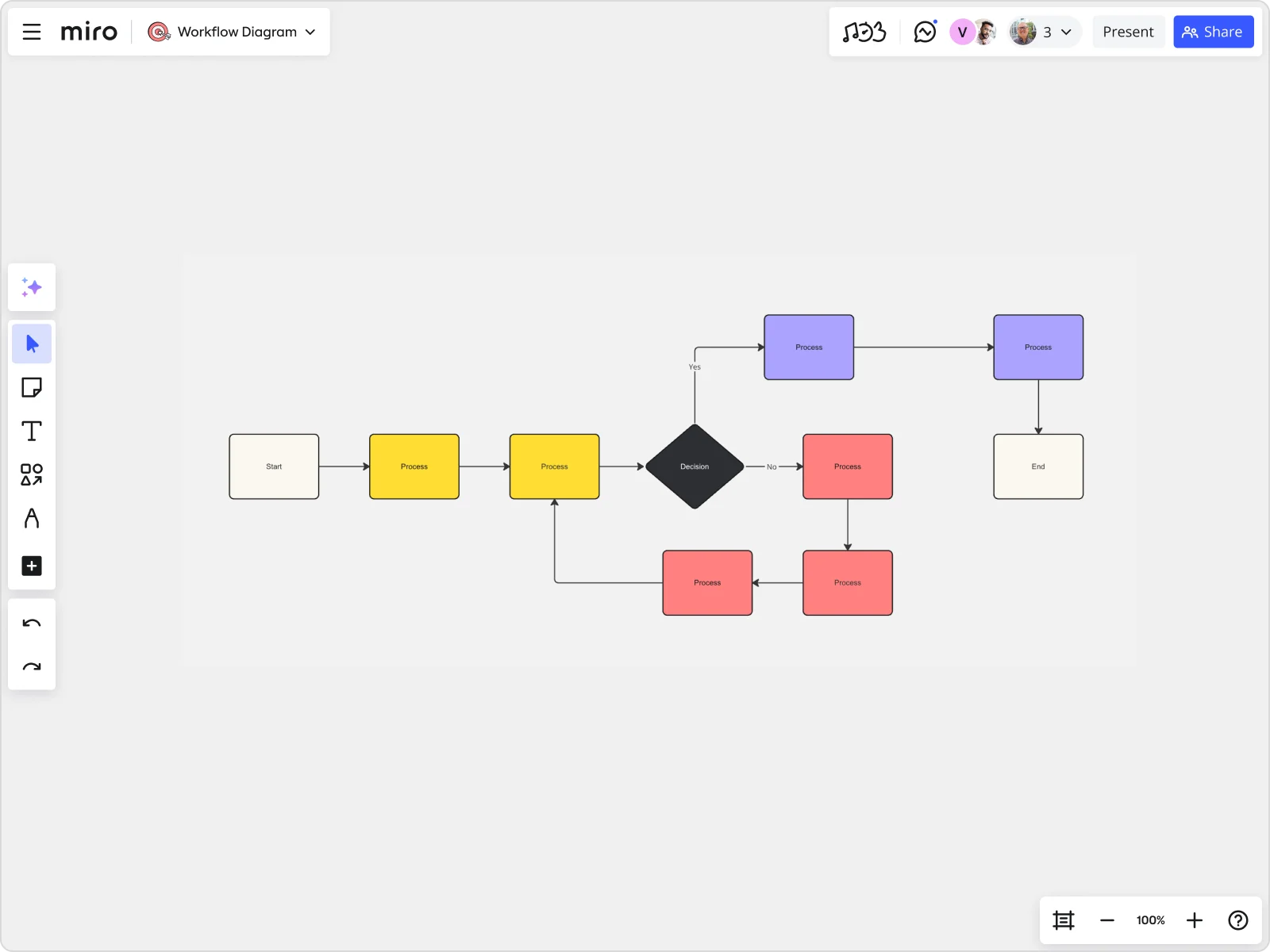

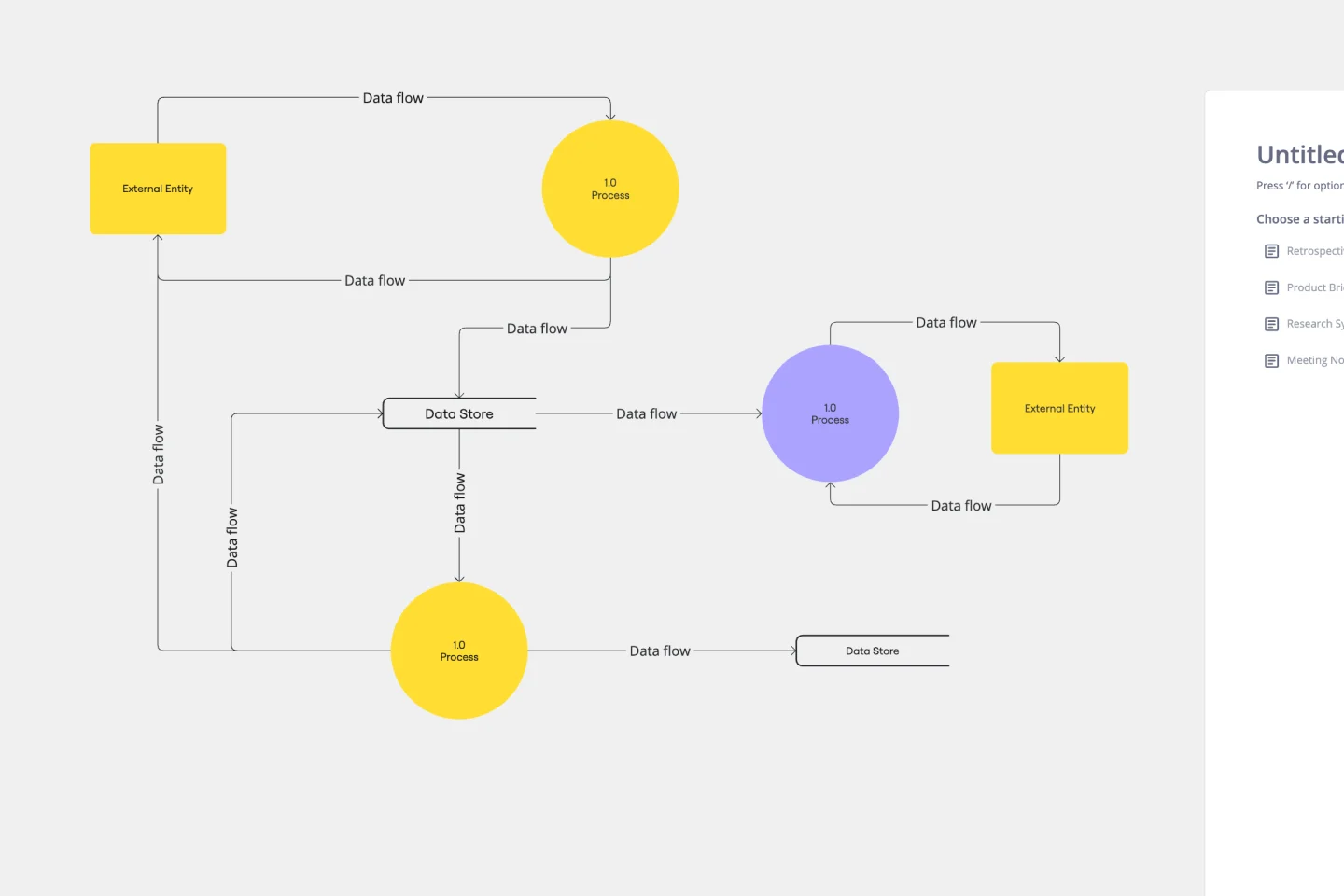

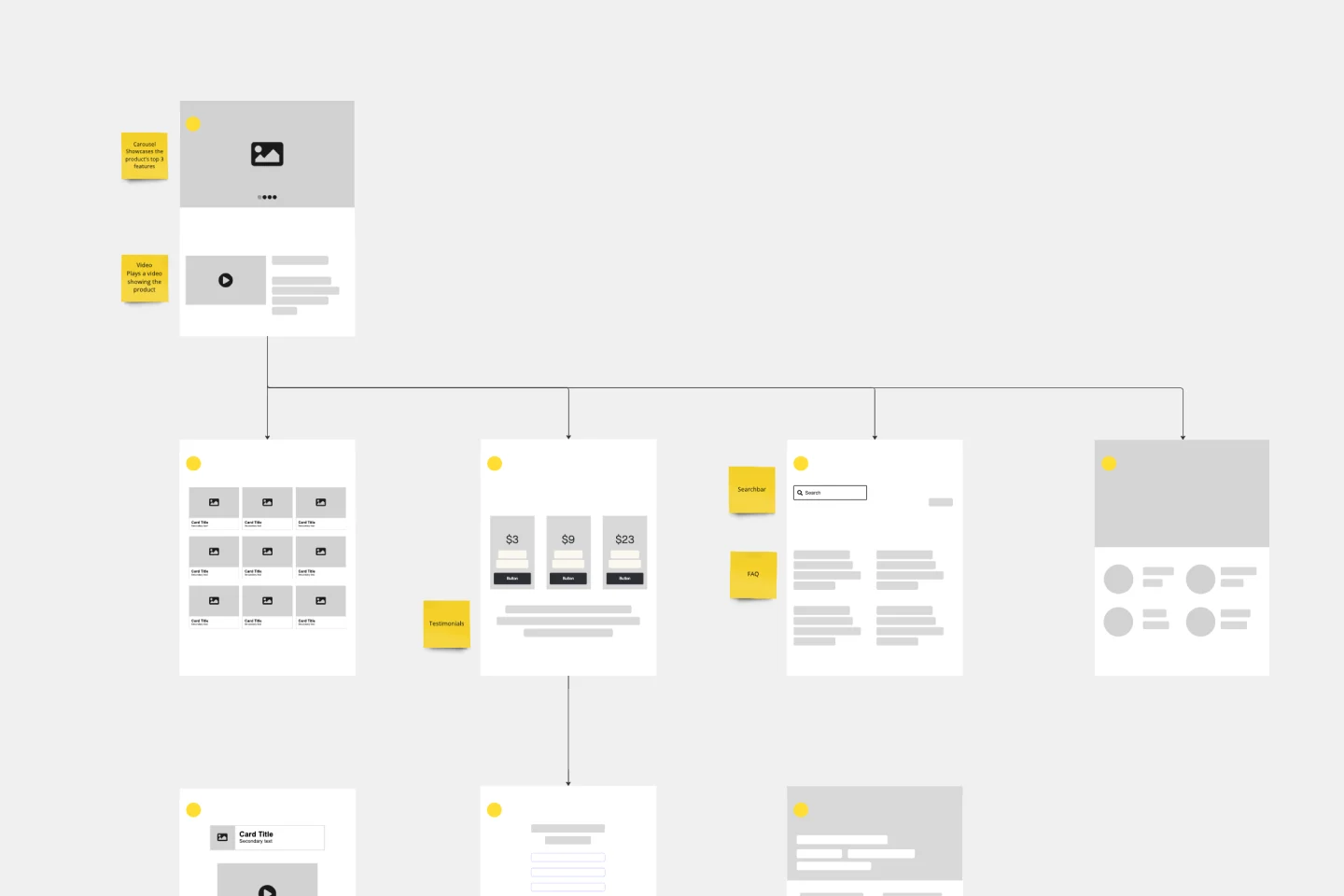

Maler til enhver prosessoversikt

Vårt omfattende malbibliotek hjelper deg med å lage den typen prosessoversikter som prosjektet krever. Begynn å jobbe med maler i Miro, sett prosjektet sammen, forbedre tydeligheten og lever resultater raskere. Vi kan hjelpe deg uansett hvilket prosjekt du jobber med.

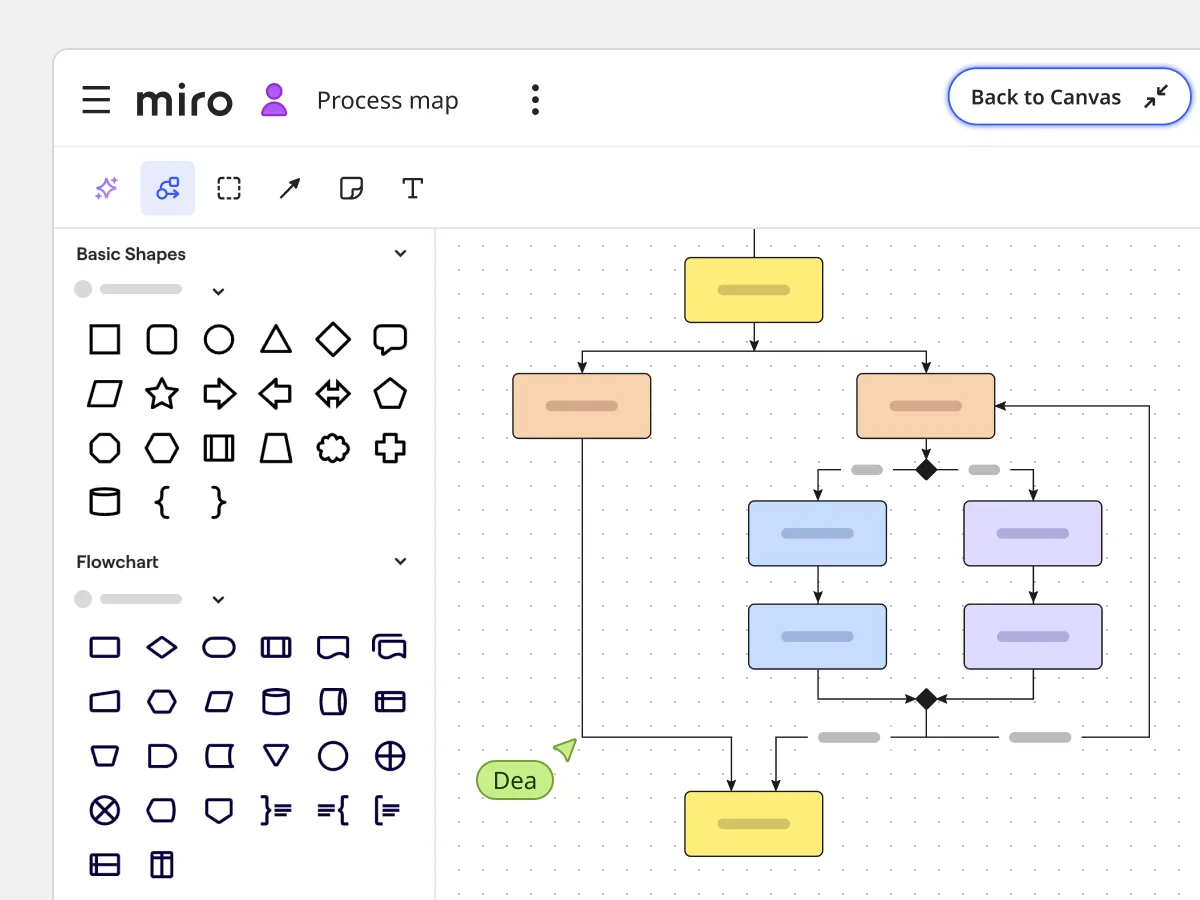

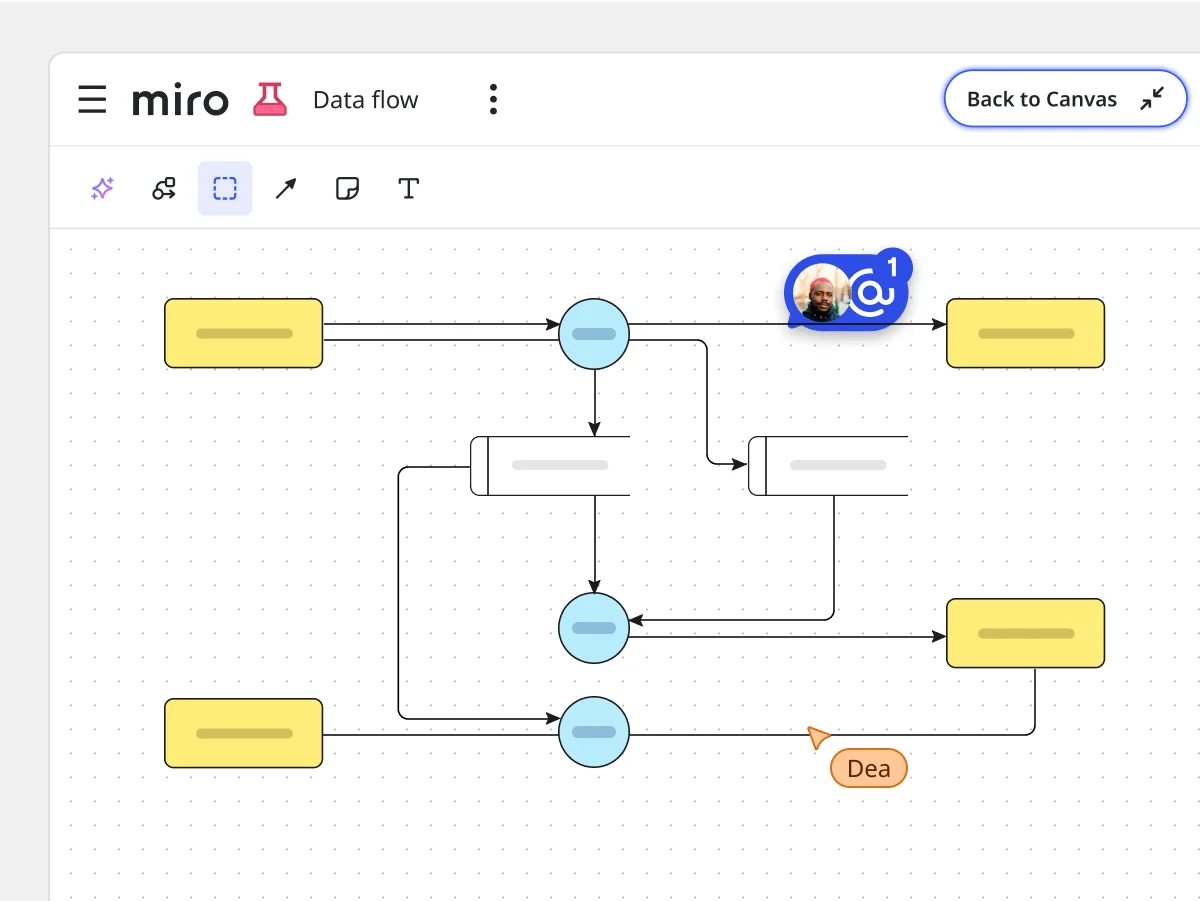

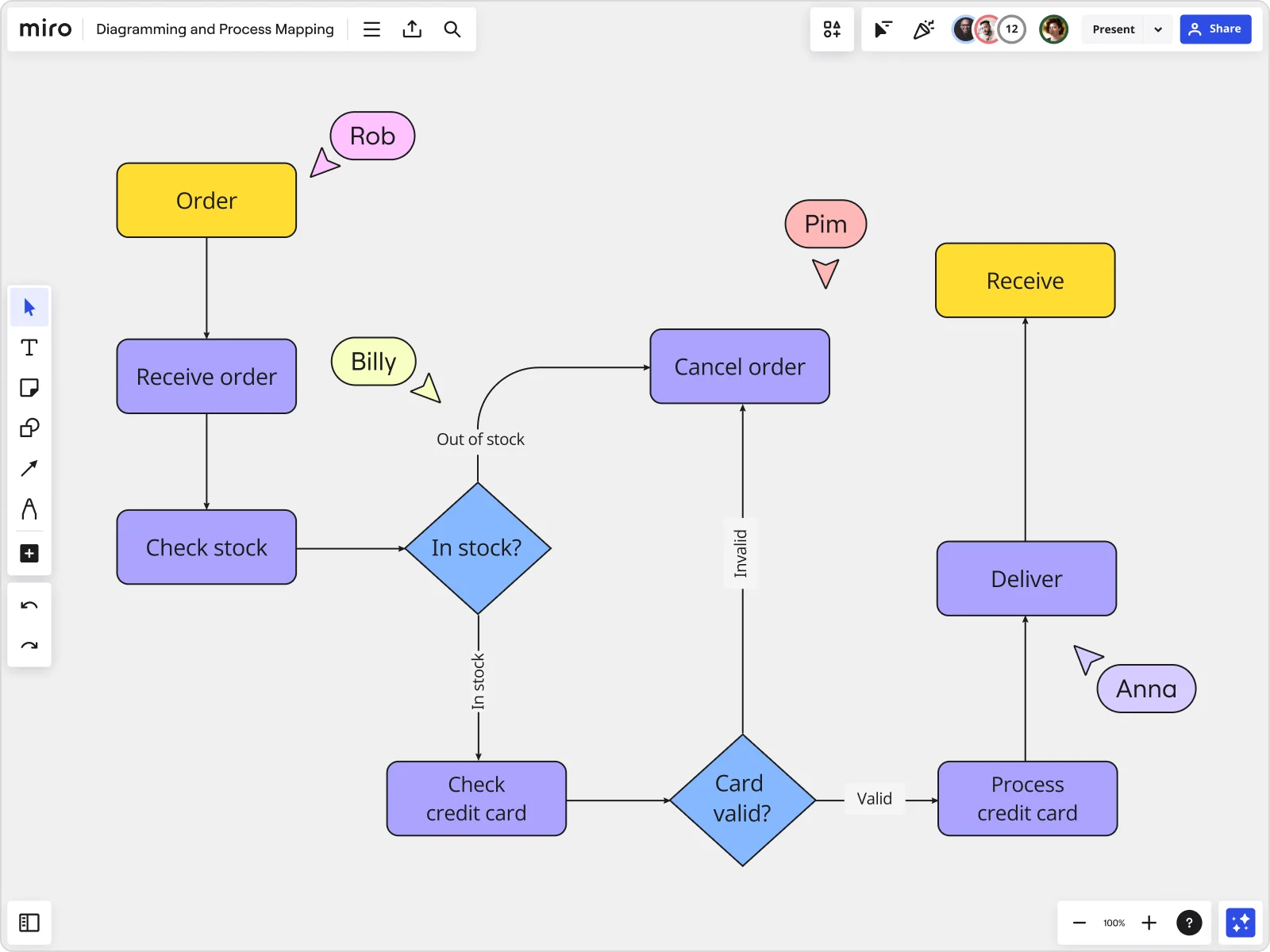

Intuitivt prosessoversiktsverktøy

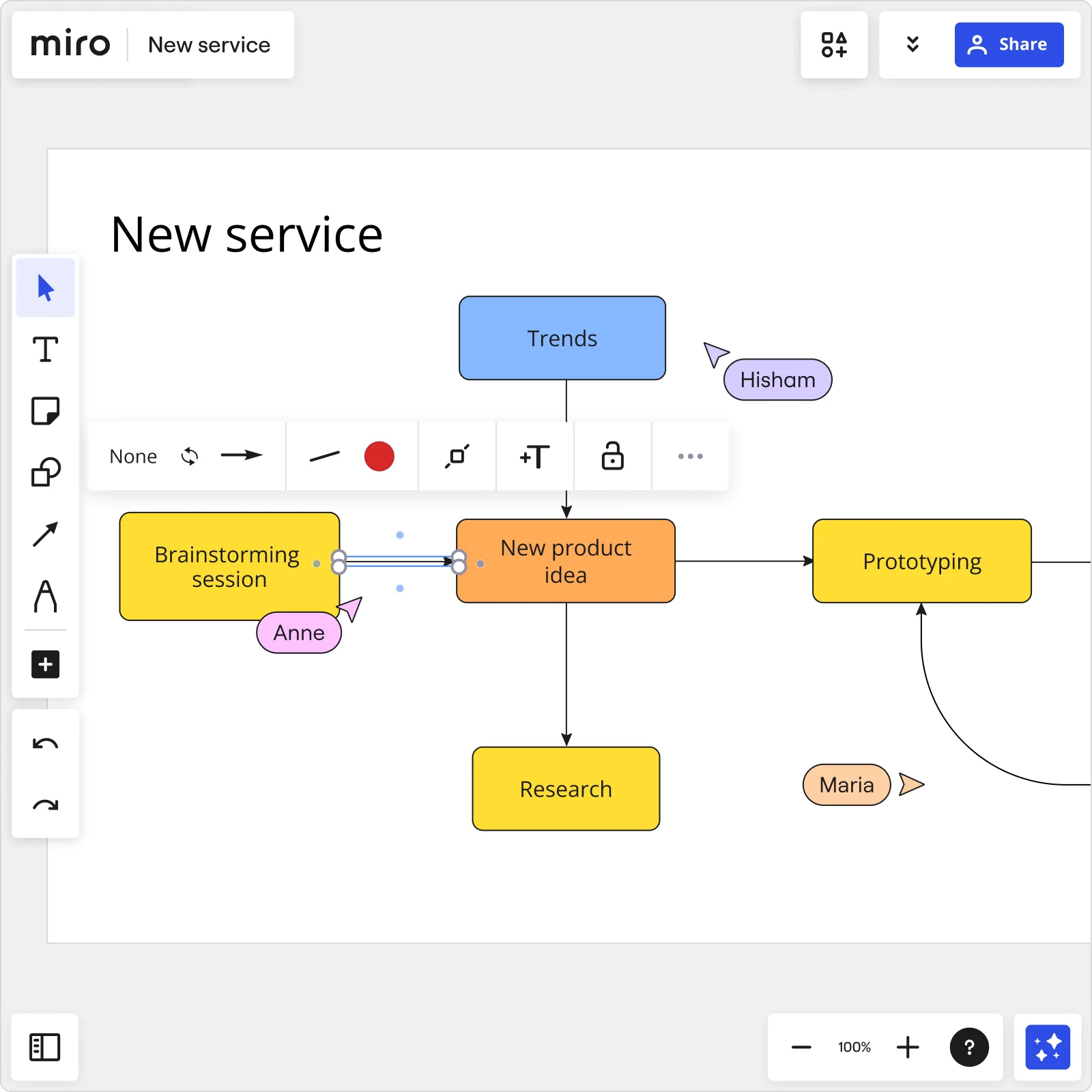

Uansett om du skaper en arbeidsprosess eller optimaliserer eksisterende prosesser, kan du bruke Miro til å lage oversikten. Gjør informasjon enda mer tilgjengelig, og vis sammenhenger mellom ulike elementer ved å legge til figurer og ikoner fra biblioteket vårt med bare ett klikk.

Skap felles forståelse

Spar tid når du bygger og kommuniserer oversikter og prosesser ved å bruke et omfattende bibliotek med gratis figurer, maler og koblinger.

Hvorfor Miro er det perfekte verktøyet for prosessoversikter

Lag profesjonelle prosessoversikter

Bruk våre stylingverktøy for å forenkle kompleks informasjon. Bla gjennom ikonene og fargekodene våre, og legg til koblinger og innbygginger i prosessoversikten din. Integrasjoner, for eksempel med Google Docs, lar deg redigere filer direkte i Miro og uten å duplisere arbeidet.

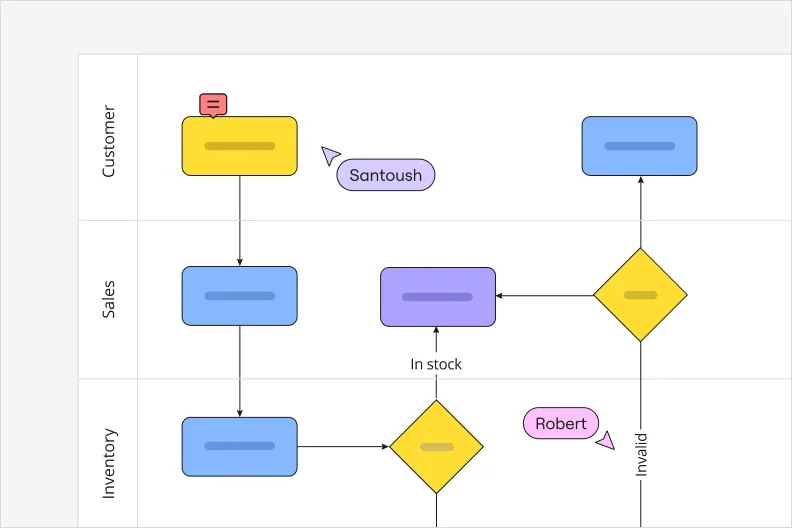

Prosessoversikt for hybridteam

Miros visuelle samarbeidsplattform er det perfekte verktøyet for prosessoversikter og distribuerte, samlokaliserte team. Sammen med teamet ditt kan du raskt utforme og kartlegge hele prosesser med verktøyet vårt, uansett hvor du er.

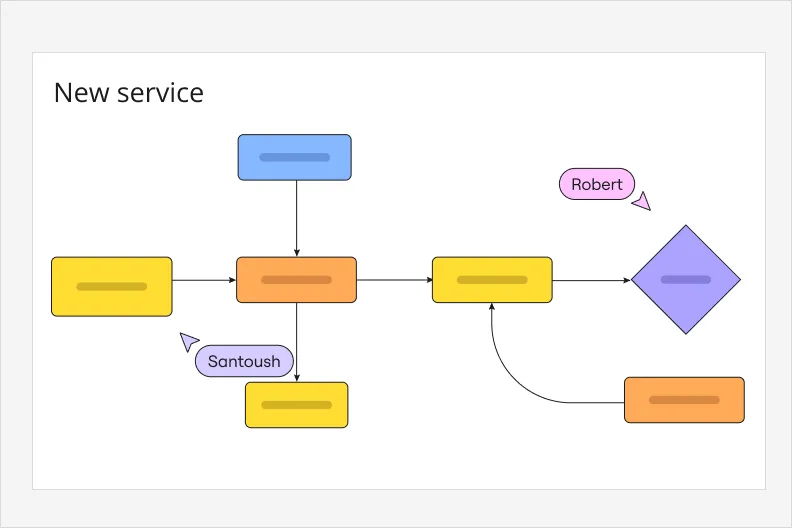

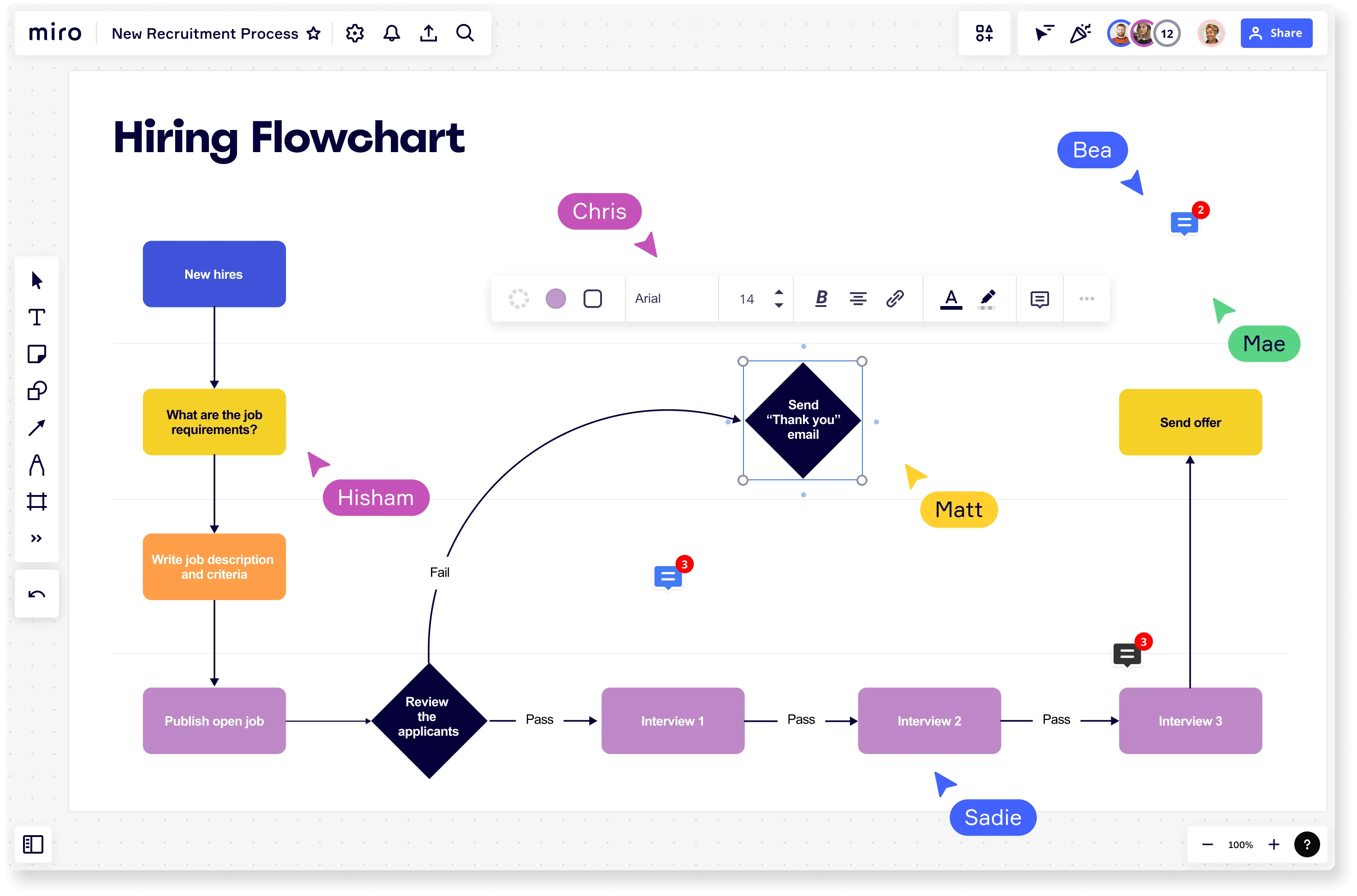

Iverksett tiltak og hold alle samstemte

Hold alle bokstavelig talt på samme side ved å holde kick-off-møter og lage handlingsplaner på én felles plass. Etter å ha fullført prosessoversikten din kan du legge til handlingsrettede elementer med prosjektstyringsmaler og konvertere dem til saker på en og samme tavle. Miro integreres enkelt med verktøy som Jira og Asana.

Et prosessoversiktsverktøy som er enkelt å dele

Få tilbakemeldinger, gjør endringer og hold ting organisert med omfattende oversikter over kommentarer og iterasjoner. Gi teammedlemmene dine tilgang til prosessoversiktene dine, arbeid direkte med dem på tavler eller eksporter tavler som bilder for bruk i presentasjoner. I tillegg kan du også bygge inn tavlene dine direkte i verktøy som Confluence og Microsoft Teams.

Tilhørende maler

Hvordan lage en prosessoversikt på få minutter

The world's most innovative companies are collaborating in Miro, everyday

«Med Miro gikk vi fra prosjektbeskrivelse til markedslansering på 10 måneder. Det tar vanligvis 3 år hos PepsiCo.»

Caroline de Diego

Senior Manager, Global Design and Marketing Innovation hos PepsiCo

«Å samle alle for å planlegge i Miro betyr at de mest innflytelsesrike initiativene vil skje til rett tid.»

Lucy Starling

Product Operations Lead hos Asos

Teamet var i gang på bare 10 minutter, klare til å bruke Miro for seminarer. Å få organisasjonen vår til å ta i bruk dette produktet var en selvfølge.»

Konrad Grzegory

Agile Transformation Lead hos CD PROJEKT RED

«Miro-malene var avgjørende for oss; de hjalp oss med å gå fra ingenting til en fullstendig plan der vi kunne kartlegge aktiviteter, ideer og avhengighetsforhold.»

Marc Zukerman

Senior Director of Project Management i Hearst

"Miro lar alle teamene våre innrette seg etter visse verktøy og modeller: de jobber uavhengig og lager produkter som virkelig oppfyller kundenes behov."

Luke Pittar

Sustainability Innovation og Design Coach i The Warehouse Group

«For å være virkelig nyskapende må alle ha en stemme, og alle må kunne iterere på hverandres ideer. Det har Miro gjort mulig for oss.»

Brian Chiccotelli

Learning Experience Designer i HP

Users love Miro for end-to-end innovation. We're the G2 leader in visual collaboration platforms and are rated in the top 50 enterprise tools. Miro helps large companies get meaningful work done.

Top 50 Products for Enterprise

G2 reviews

Spørsmål og svar om prosessoversiktsverktøyet

Hvordan bruker jeg prosessoversikten?

Uansett spesifikk type viser alle prosessoversikter verdifull informasjon om prosesser, metoder, trinnvise veiledninger og interessenter i et prosjekt. Bruk en prosessoversikt for prosjektledelse, uanstrengt samarbeid og rask informasjonsdeling.

Hvilket er det beste gratisprogrammet for å lage en prosessoversikt?

Miros prosessoversiktsverktøy er gratis, og du kan bruke det til å lage hvilket som helst skjema du trenger. Vi gjør det enkelt. Du trenger ikke å være proff for å lage din egen prosessoversikt i Miro. Våre verktøyfunksjoner er enkle og intuitive. Kom i gang ved å skissere en prosessoversikt med figurer og linjer, og legg deretter til farger og ikoner fra ikonbiblioteket vårt. Prøv det gratis nå, og gi oss beskjed om det fungerer for deg.