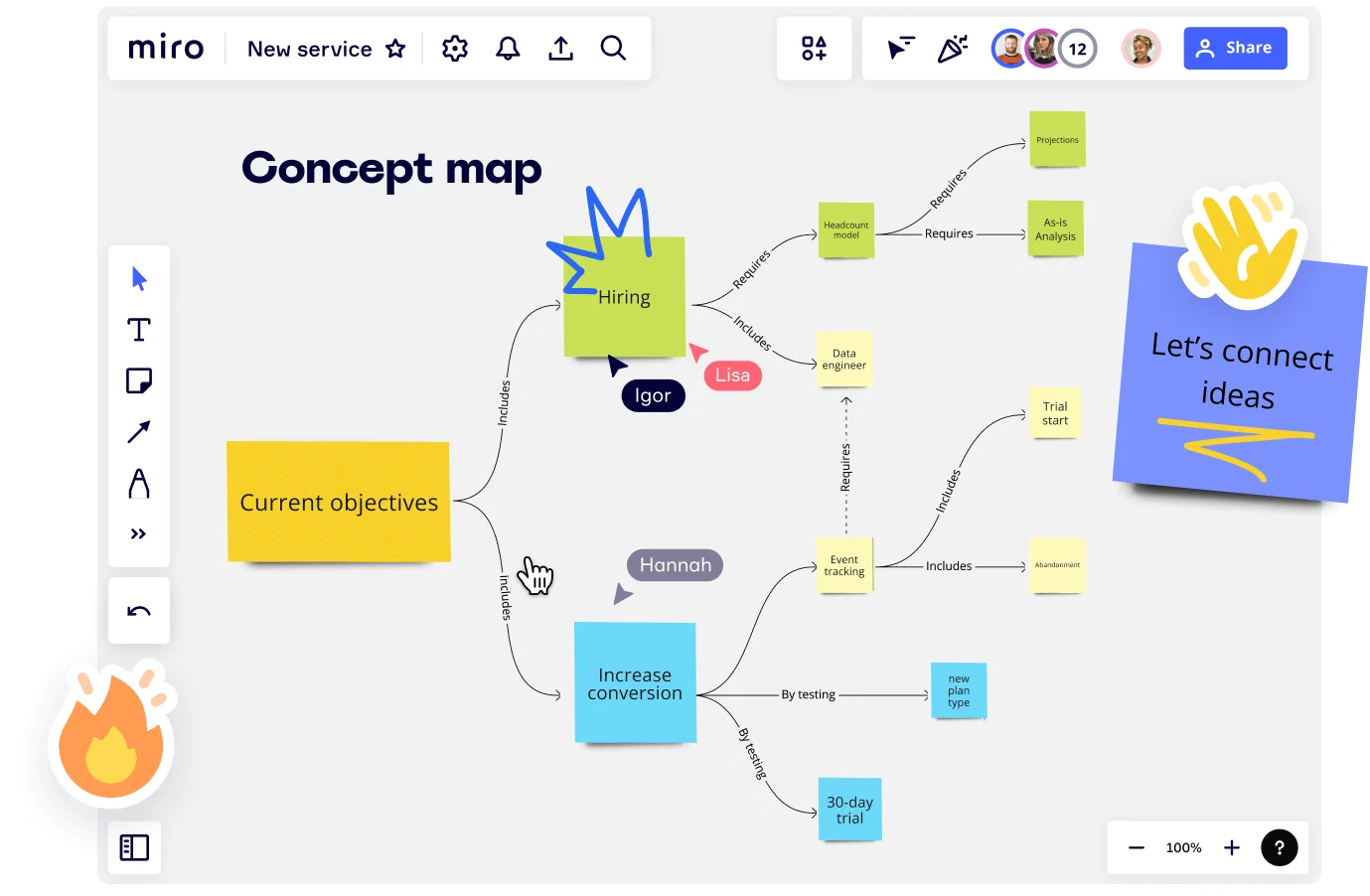

A ferramenta para criar Mapas Mentais online

Uma maneira rápida e fácil para as equipes se reunirem, organizarem e estruturarem as ideias. Comece com um de nossos modelos de mapas mentais criativos – é grátis.

Transforme tópicos complexos em ideias simples

Analise tópicos ou problemas complexos dividindo as causas e explorando suas relações; use cores, imagens e ramificações ao criar um mapa mental online na Miro.

Expanda suas ideias infinitamente com a Miro Assist para mapas mentais

Acelere tarefas manuais entediantes, como detalhar ideias de campanhas, descrever projetos e criar diagramas usando a funcionalidade Miro Assist. Use a inteligência artificial incorporada à ferramenta de mapas mentais para ajudar você a gerar ideias.

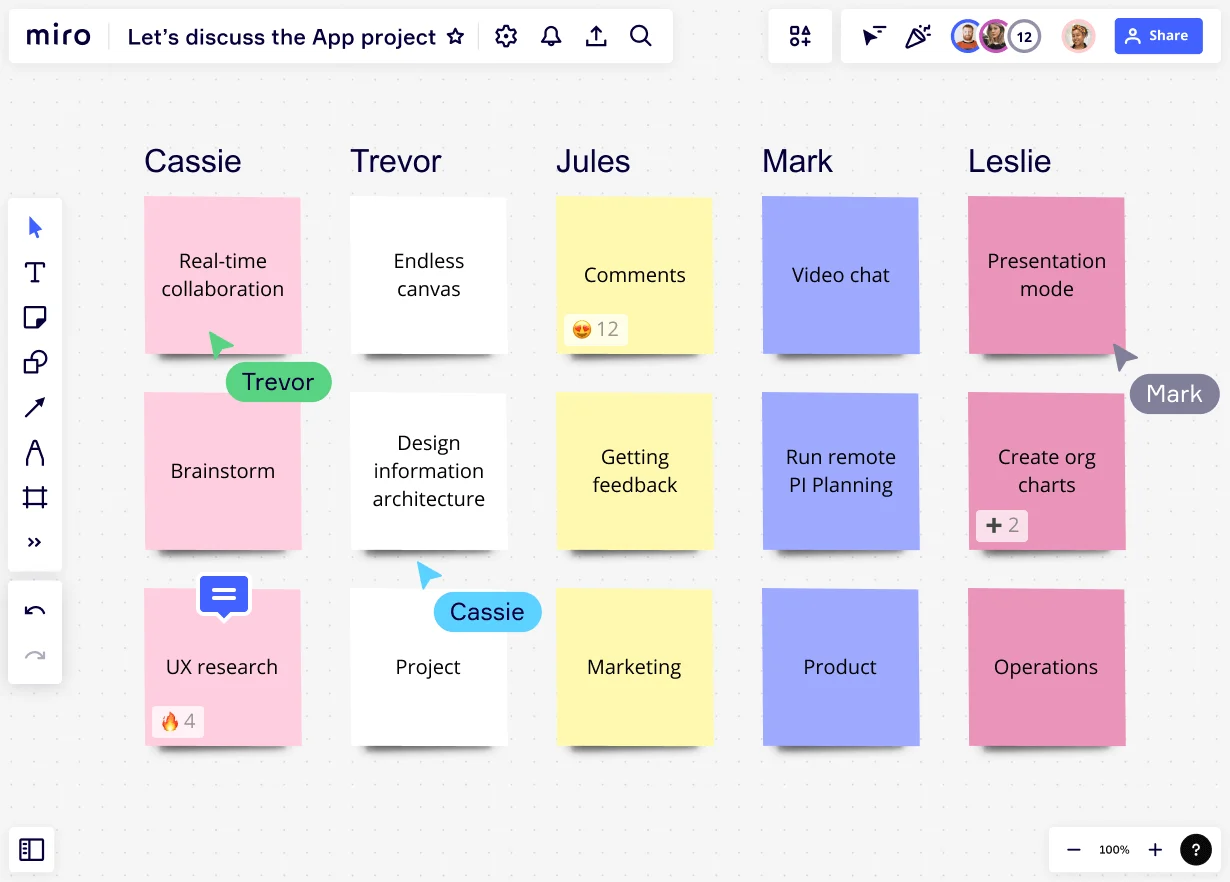

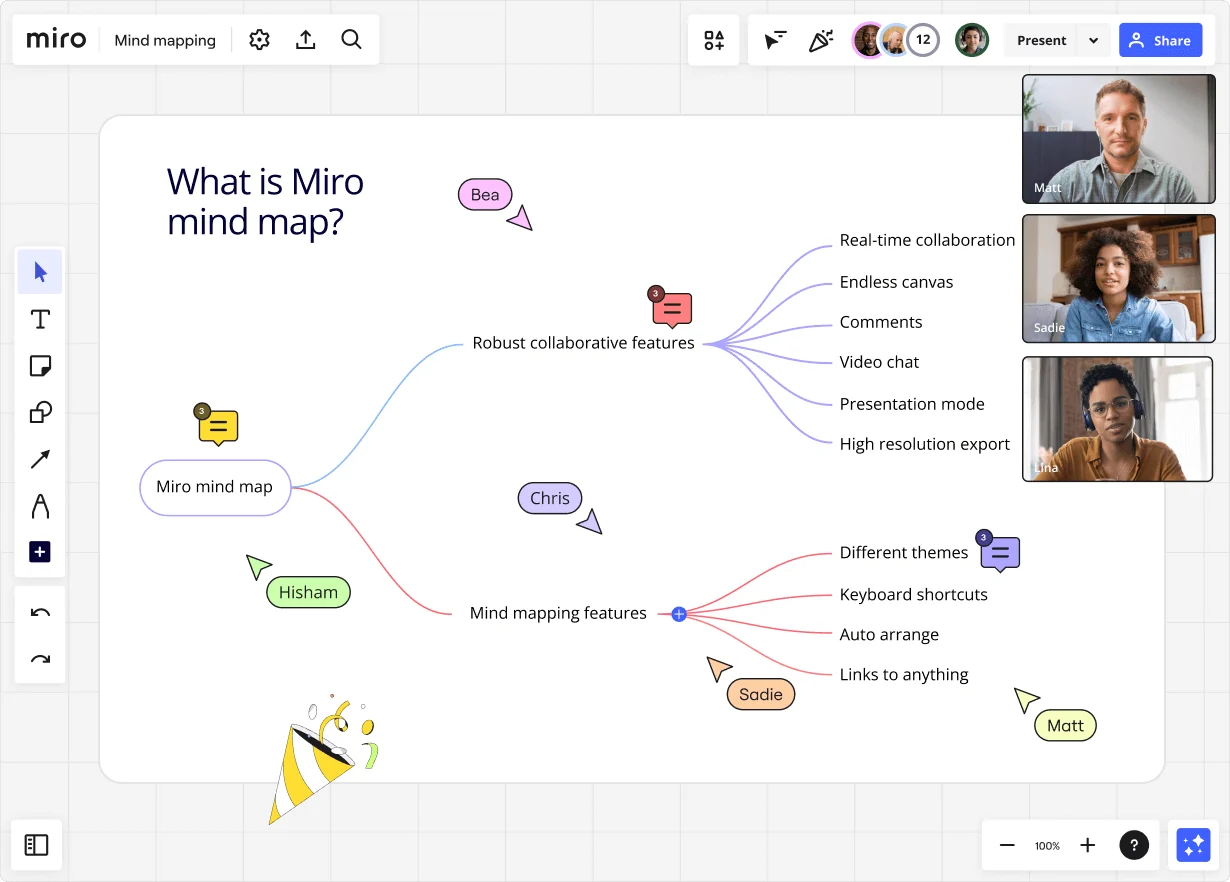

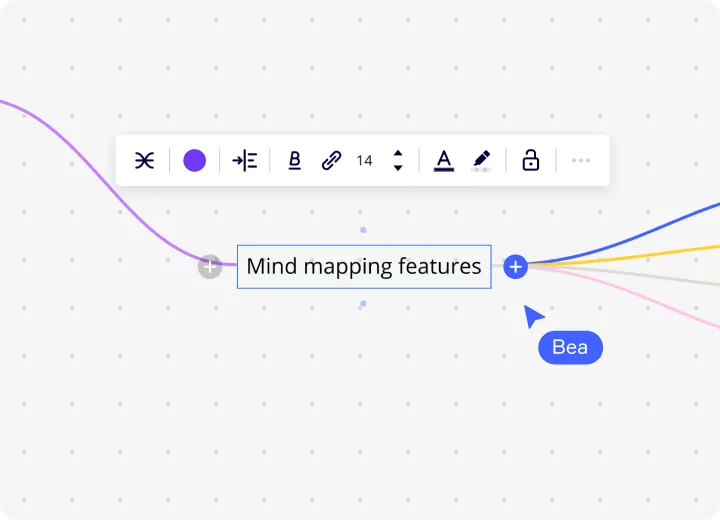

Crie Mapas Mentais colaborativos

Use o nosso site para fazer mapas mentais colaborativos online com seus colegas de equipe. Você pode convidar quantos colaboradores quiser para editar o mapa mental ao mesmo tempo, online ou de forma assíncrona. Assim fica muito mais divertido criar mapas mentais em equipe!

Por que é melhor fazer um mapa mental online na Miro?

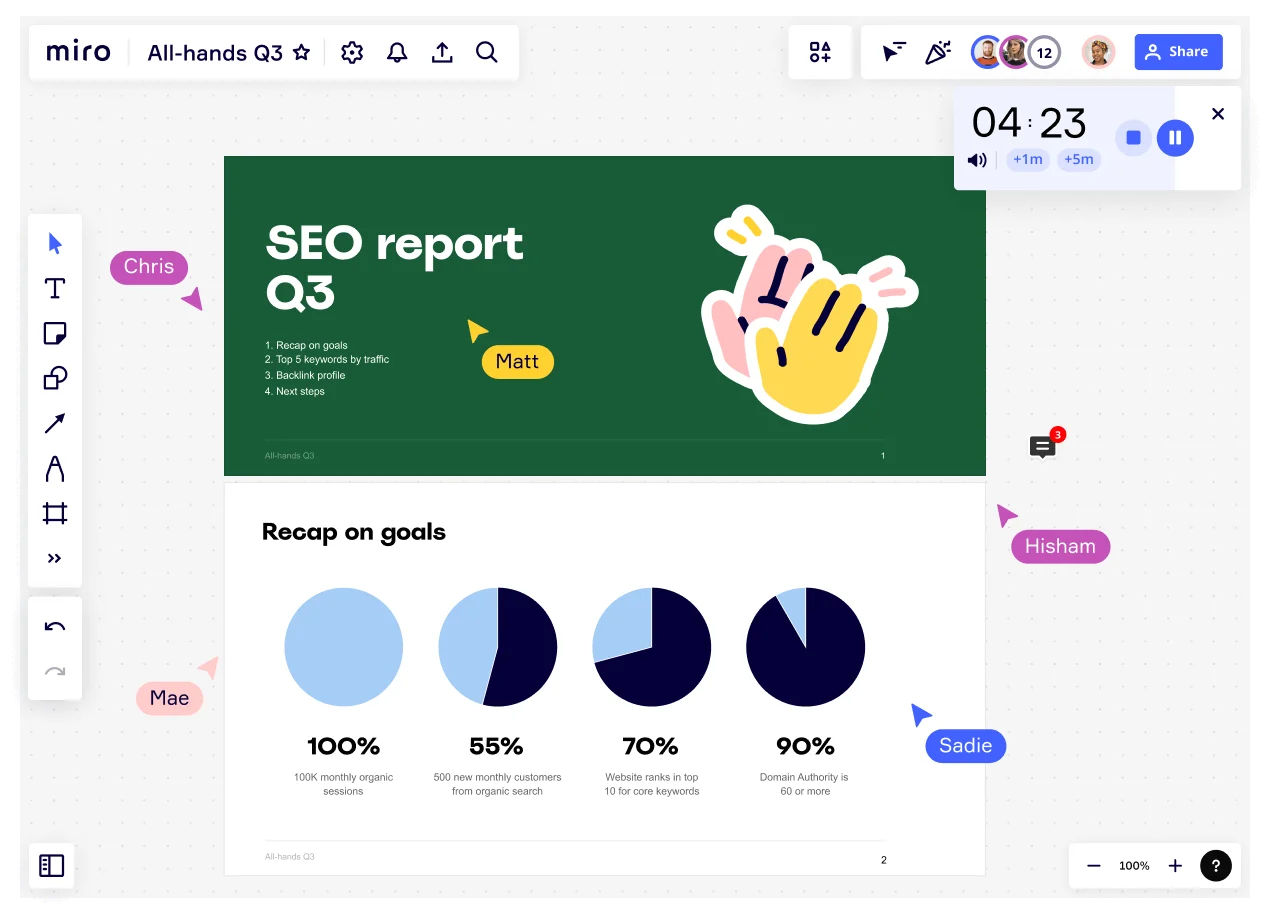

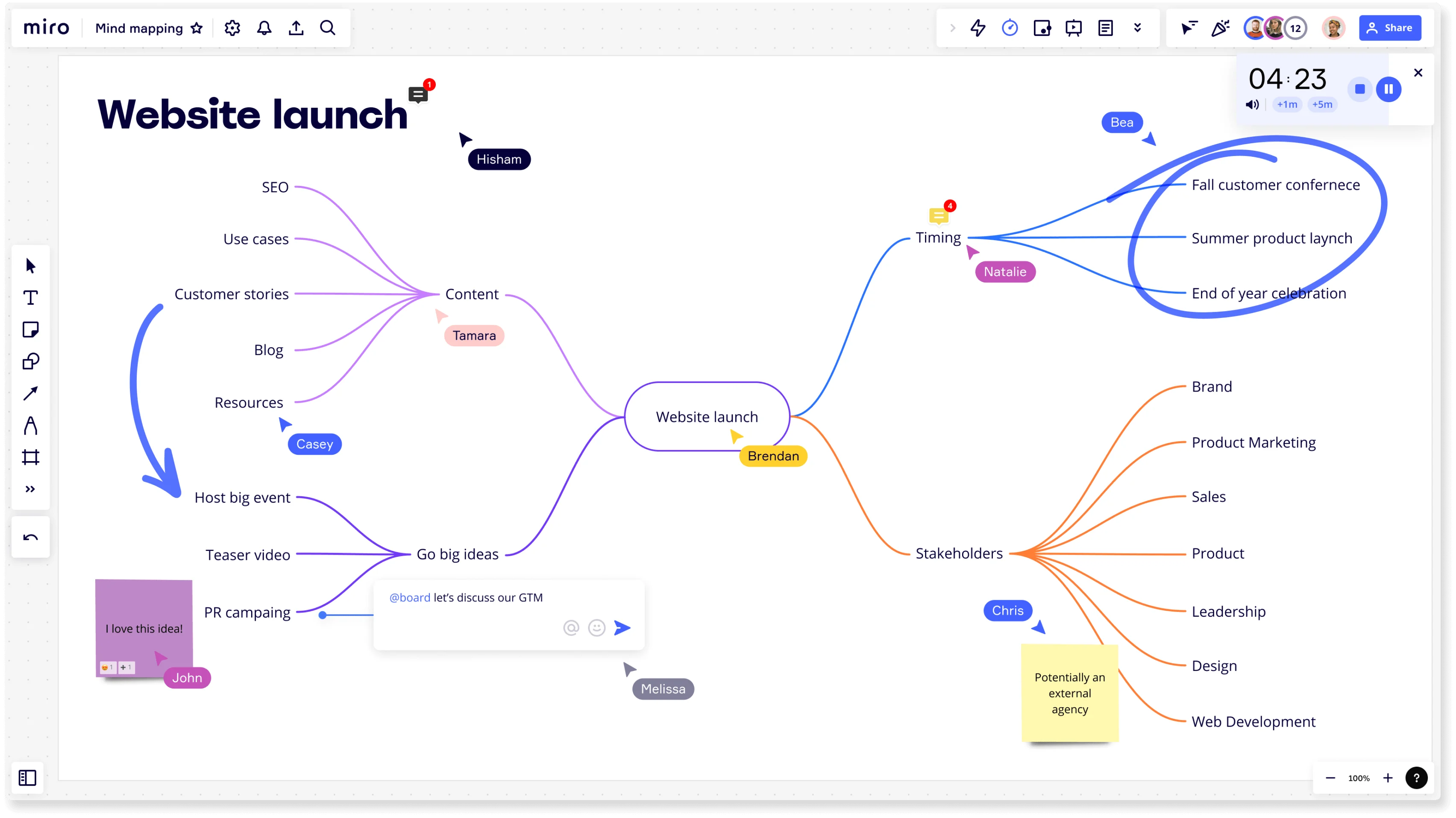

Modo apresentação

Ative o modo de apresentação ou divida seu mapa mental em diferentes quadros para apresentar como se fossem slides.

Comunicação perfeita

Vídeo, bate-papo, @menções, emojis e comentários para manter a comunicação em dia.

Colabore em tempo real

Várias pessoas da equipe podem cocriar de forma simultânea na ferramenta.

Canvas infinito

Adicione imagens, textos, vídeos, mapas mentais ou qualquer outro conteúdo no canvas infinito do seu board na Miro.

Cronômetro e votação

Gerencie melhor o tempo e faça votações facilmente. Deixe sua reunião mais produtiva.

Coleção de templates

Escolha entre mais de 300 modelos prontos, editáveis e gratuitos da Miro. Inspire-se e personalize seu mapa mental online da forma que preferir.

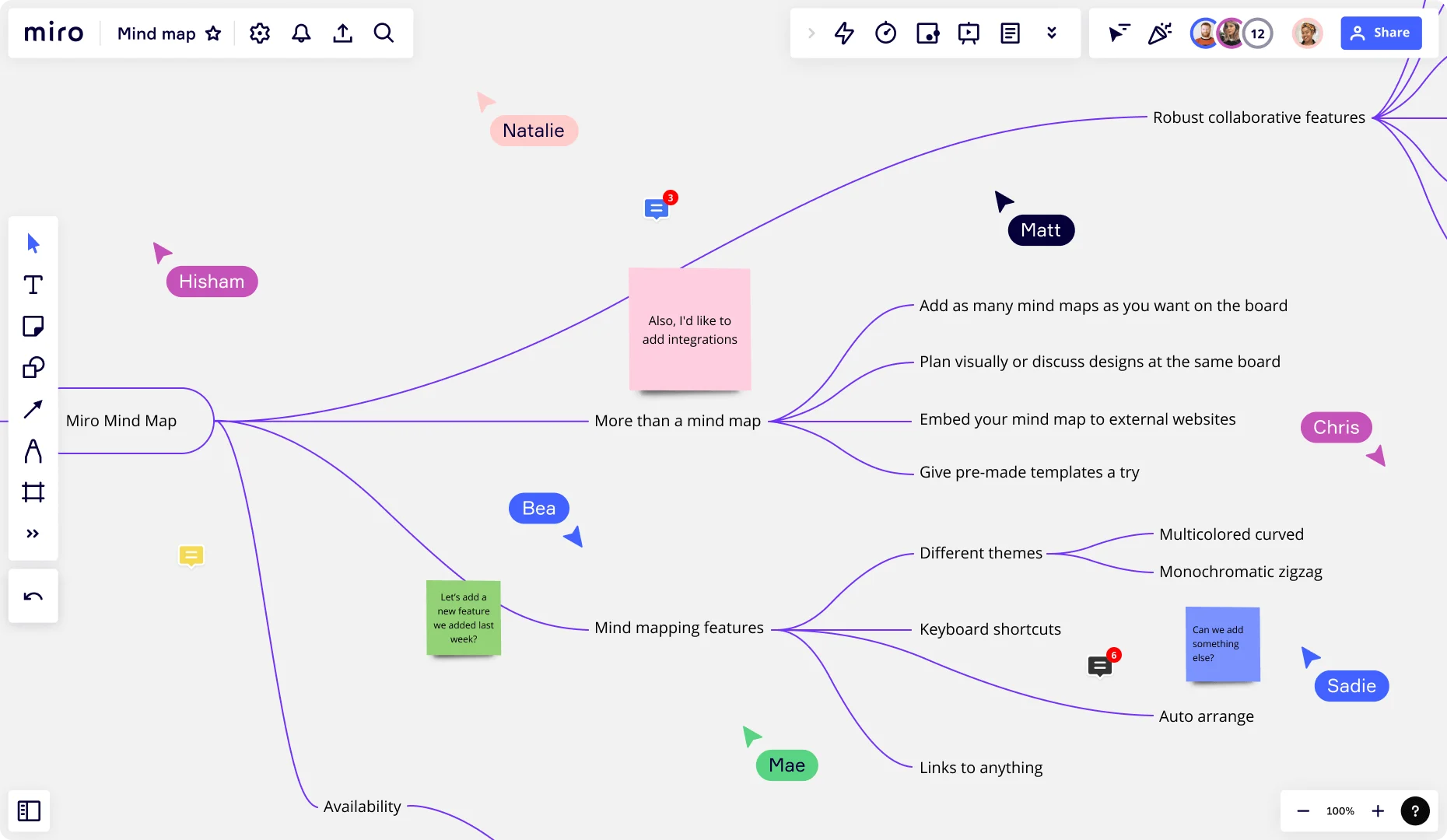

Mais do que somente um site para fazer mapas mentais

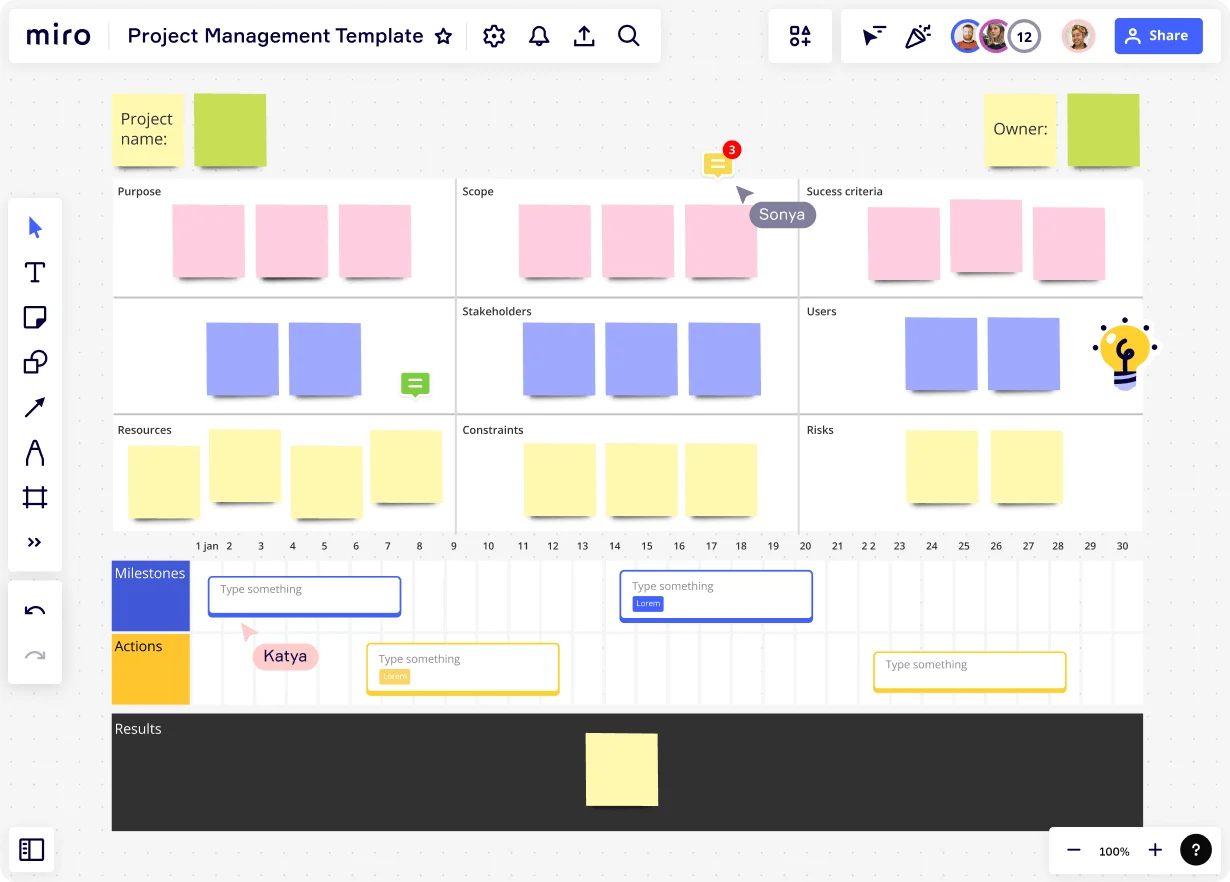

A plataforma de colaboração visual da Miro ajuda times e indíviduos do mundo todo a fazer brainstormings, planejar projetos, mapear a arquitetura da informação, criar organogramas, desenvolver estratégias de negócios e, claro, criar mapas mentais. Todos podem trabalhar ao mesmo tempo em um espaço de trabalho online e colaborativo.

Libere o potencial da sua equipe e dê vida aos seus projetos com a Miro. Um espaço de trabalho completo com ferramentas de gestão de projetos e muito mais.

Saiba mais

Aprimore suas apresentações e comunique visualmente suas ideias, projetos e tudo o que precisar. A Miro ajuda você a ganhar mais confiança e manter sua audiência engajada.

Saiba mais

Libere as ideias mais criativas em uma tela infinita e colabore em tempo real de qualquer lugar. Use a Miro para organizar insights em diversos formatos como comentários, votações, diagramas e muito mais.

Saiba mais

Criar mapas conceituais criativos online é uma maneira fácil e rápida para times gerarem e estruturarem novas ideias e inovar sempre.

Saiba mais

Modelos editáveis prontos para uso

Melhore suas sessões de brainstorming com esta técnica única.

Saiba mais

Defina objetivos para o negócio e descreva como alcançá-los.

Saiba mais

Gere novas ideias e resolva problemas com esta técnica de associação.

Saiba mais

Desenvolva entendimento e inovação em conjunto com o seu time.

Saiba mais

Explore, planeje e preveja vários resultados possíveis para suas decisões.

Saiba mais

Acompanhe os cronogramas, tarefas e dependências do projeto em um único olhar.

Saiba mais

Mapa mental — Perguntas frequentes

Como fazer mapas mentais criativos?

A lógica ao criar um mapa mental é sempre a mesma: uma ideia central que se conecta a conceitos relacionados. A criatividade pode vir ao usar diferente cores ou formas, mas também pode incluir imagens, emojis e outros elementos que facilitem o entendimento. Você pode começar rapidamente com um de nossos modelos de mapa mental em branco.

Os exemplos e modelos são totalmente personalizáveis para que você possa adaptá-los de acordo com suas necessidades. A Miro oferece criação de mapas mentais exclusivos e oferece uma ampla gama de possibilidades. precisa de uma ajudinha para começar? Use as funcionalidades de IA para Mapas Mentais da Miro.

Nunca foi tão fácil fazer mapas mentais!

Para que serve um mapa mental?

As ferramentas de mapas mentais online e colaborativas são ótimas para quando você precisa organizar ideias, pensamentos ou conceitos e ver como eles estão relacionados. Eles são especialmente úteis para sessões de brainstorming, workshops para resolução de problemas ou para fazer anotações. Use um criador de mapa mental, como o da Miro para otimizar tempo e focar no que importa.

Criar um mapa mental na Miro é gratuito?

Sim, todos os modelos de mapa mental da Miro são 100% gratuitos e não precisam de cartão de crédito para começar. Depois de se inscrever, você pode convidar colaboradores para o seu board e começar a criar um mapa mental online imediatamente em nossa plataforma.

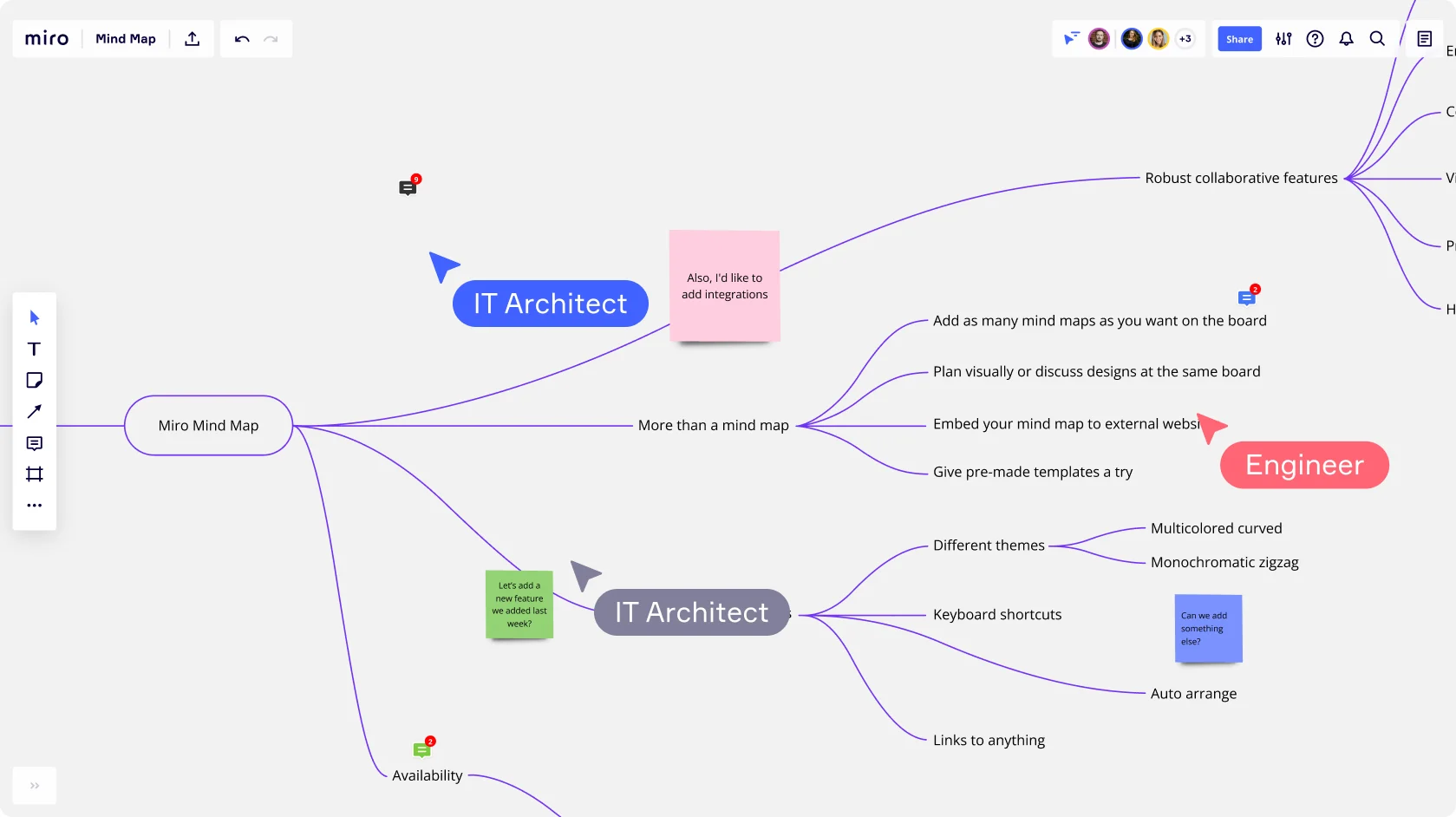

Posso compartilhar meu mapa mental com a minha equipe?

Sim, você pode fazer um mapa mental colaborativo e compartilhar com a sua equipe a qualquer momento usando o botão Compartilhar na parte superior do seu board da Miro. Você pode permitir a visualização, comentários ou edição do seu mapa mental. Também é possível baixar a versão do seu mapa mental online como PDF ou JPEG diretamente do board, caso queira um arquivo para compartilhar em outros canais, ou até mesmo criar um código de inserção para incluir em blog posts ou páginas do seu site.

Como fazer um mapa mental para brainstorming?

Para fazer um brainstorming com um mapa mental e seu time, comece com uma ideia ou problema central no meio da página ou do board. Crie algumas regras para as pessoas se prepararem para a sessão. Compartilhe o board com seu time para que todos possam colaborar simultaneamente. Há centenas de técnicas diferentes de brainstorming que você pode usar para gerar várias ideias novas rapidamente. À medida que cada ideia nova flui, basta adicioná-la a um novo ponto no seu mapa mental virtual.

Qual a diferença entre mapa mental e mapa conceitual?

Os mapas mentais e mapas conceituais se assemelham muito por terem o mesmo objetivo de explicar um conceito complexo de maneira visual, com formas geométricas, cores e textos conectados. A principal diferença é que o mapa mental geralmente parte de uma ideia central e possui ramificações para outros conceitos, enquanto o mapa conceitual pode seguir um raciocínio lógico e hierarquização das informações.

Veja mais

Crie um board em segundos

Faça como milhares de times e use a Miro para deixar o trabalho em equipe ainda melhor.