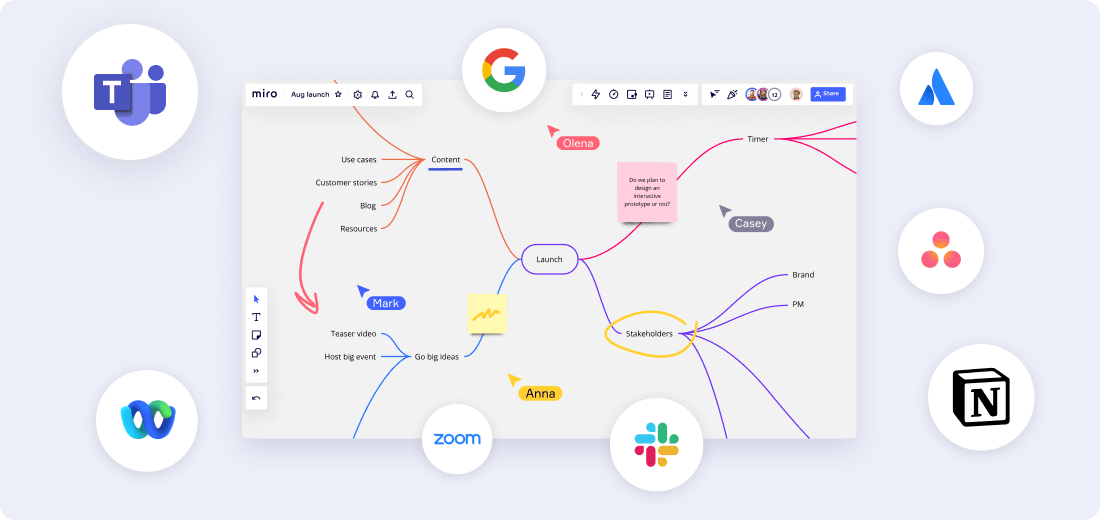

แอปและการผสานรวมมากกว่า 130 รายการ

เชื่อมต่อเครื่องมือของคุณและปิดแท็บของคุณด้วยแอปที่คุณใช้และชื่นชอบอยู่แล้ว

Skip to:

รวมทีมต่าง ๆ เข้าด้วยกันและสร้างทุกสิ่งที่คุณต้องการเพื่อพัฒนาแคมเปญที่สร้างความพึงพอใจให้กับลูกค้าและขับเคลื่อนธุรกิจไปข้างหน้า ทั้งหมดนี้รวมอยู่ในที่เดียว

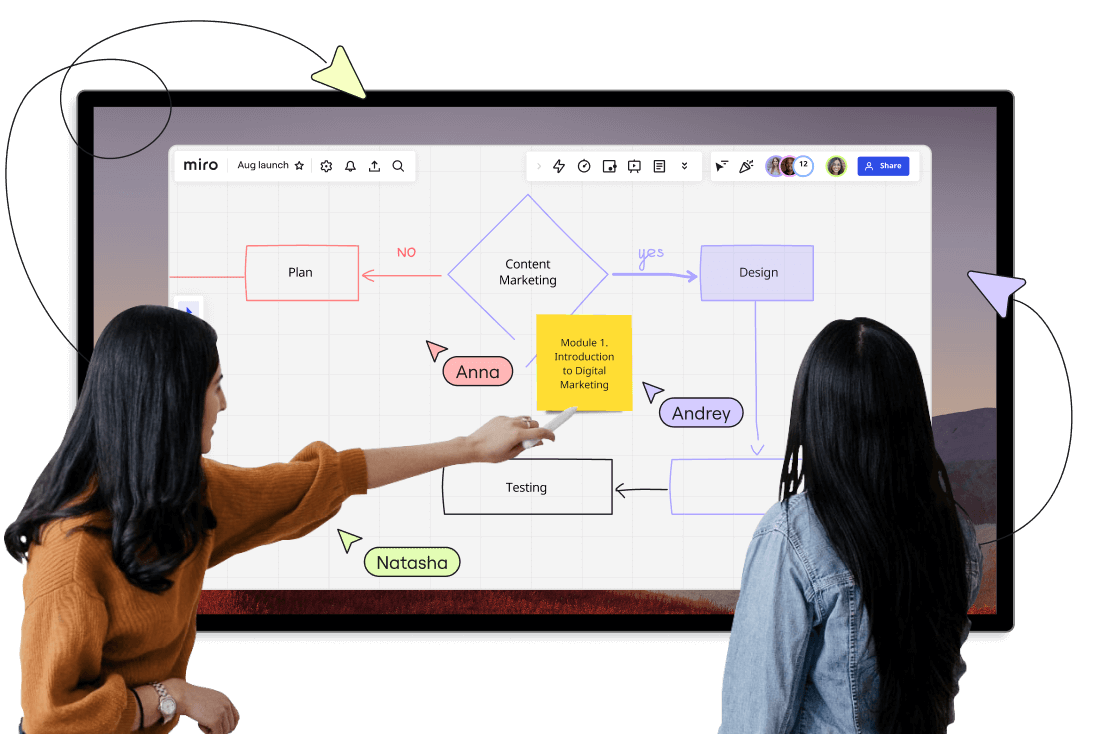

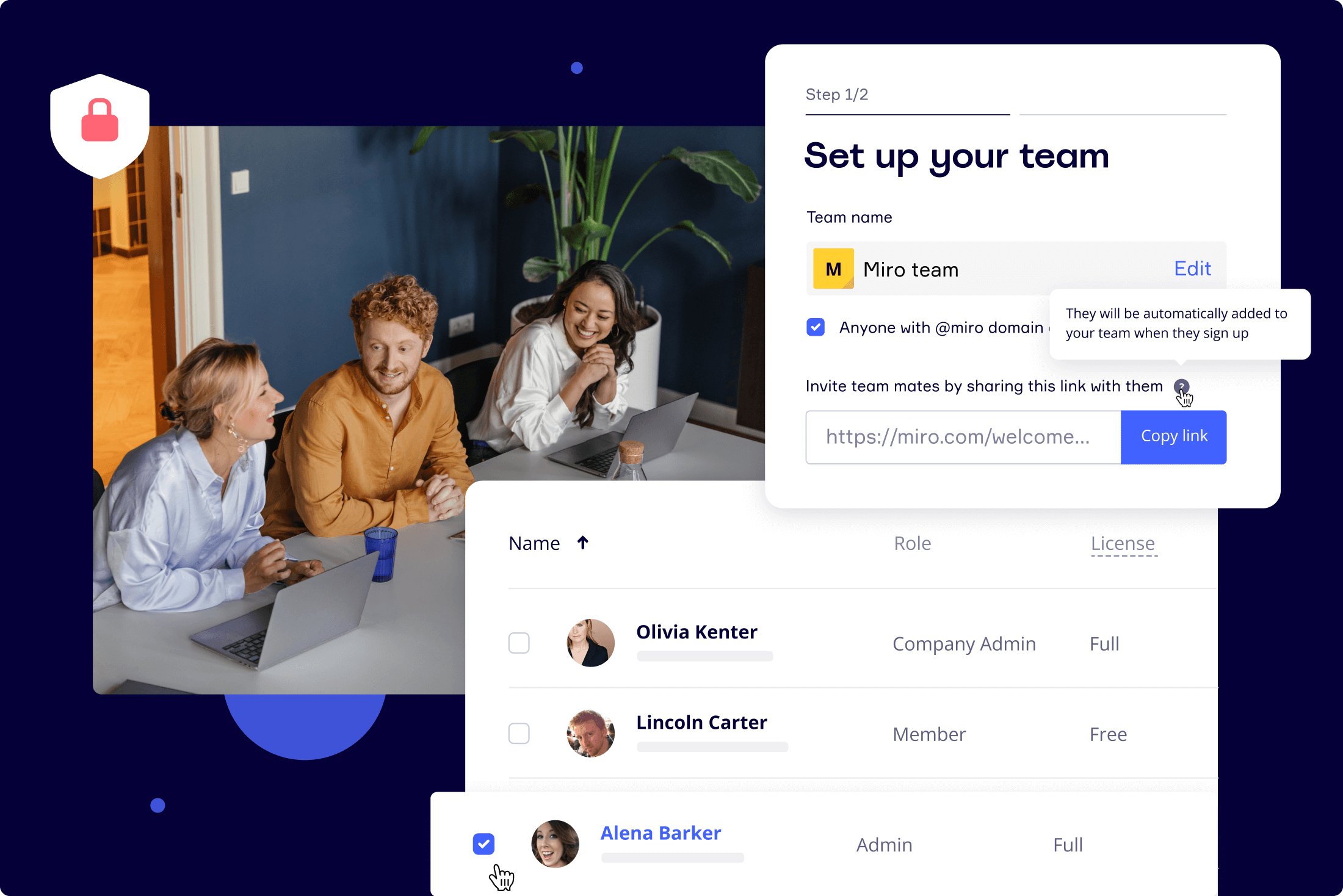

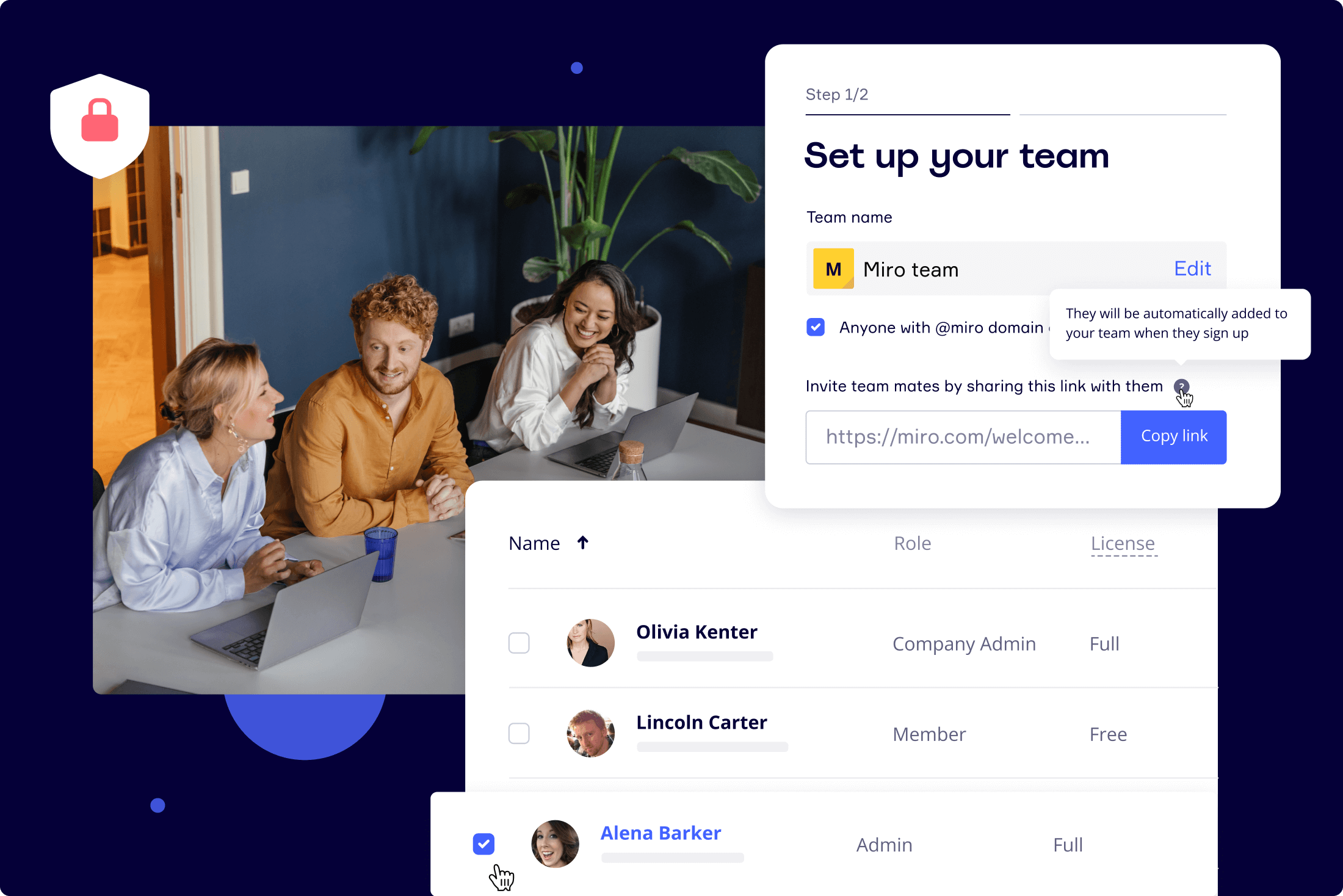

ประสานการทำงานร่วมกับทีมของคุณภายในไม่กี่นาที

ผู้ใช้ 70 ล้านคนทั่วโลกไว้วางใจ Miro

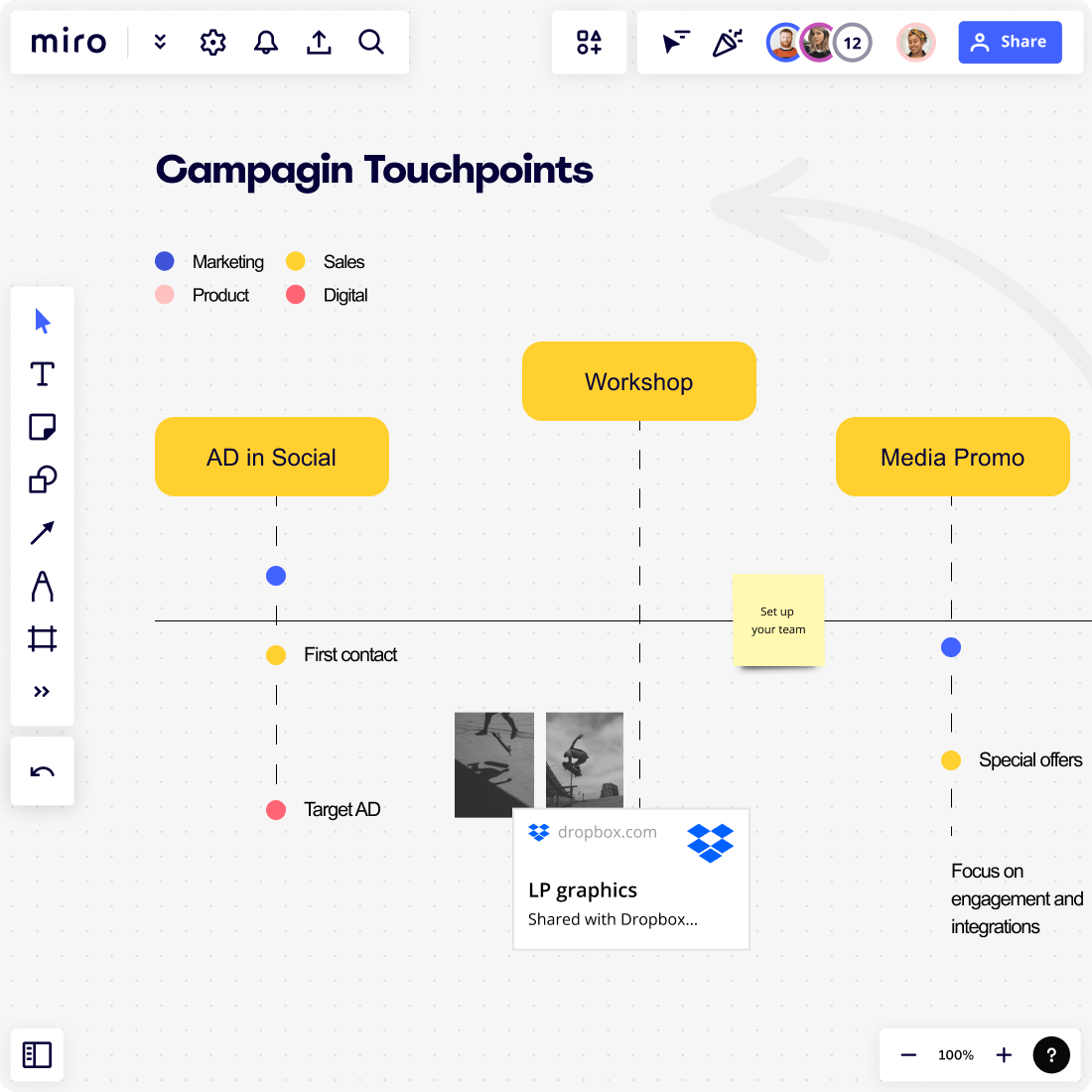

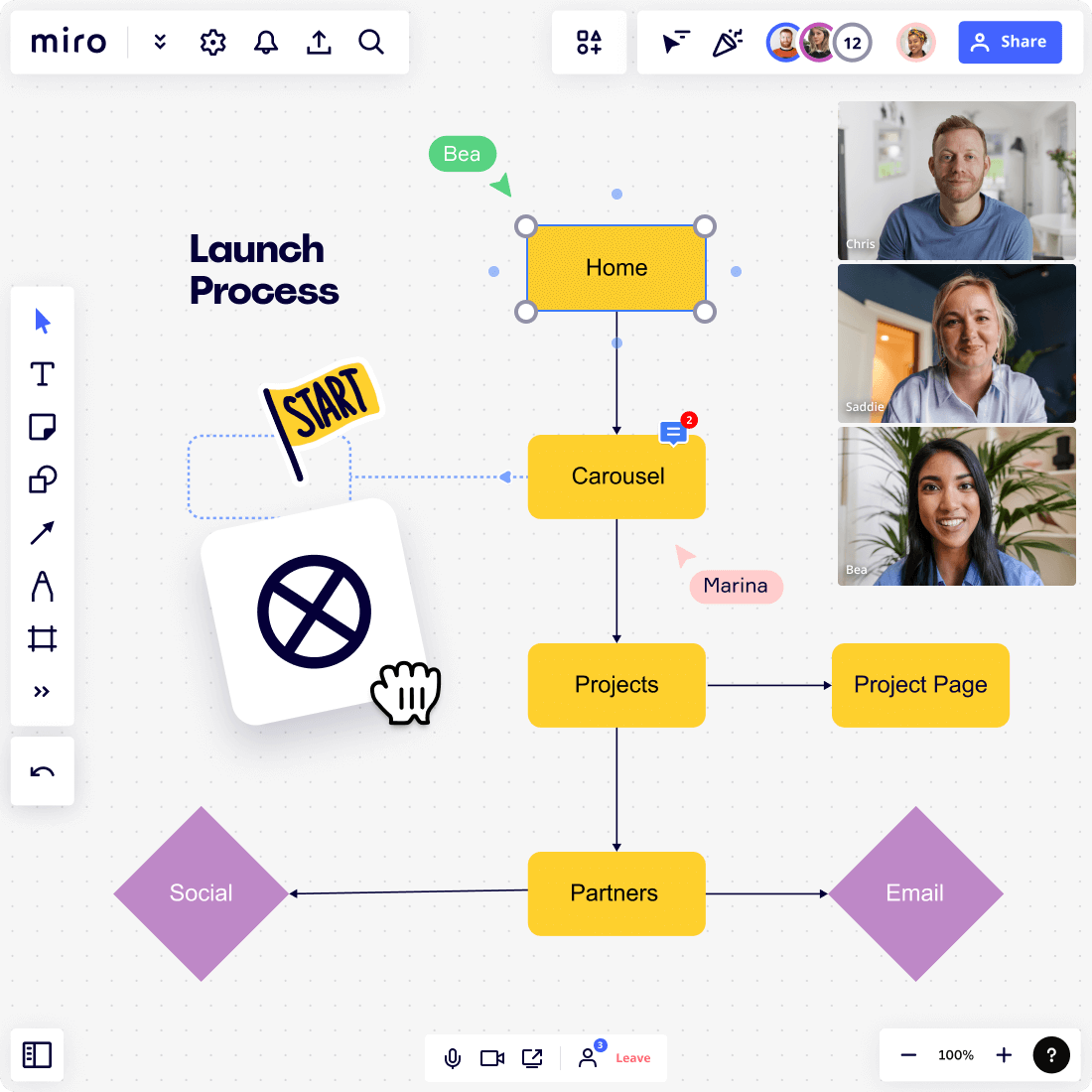

ค้นหาวิธีรวบรวมข้อมูลและทำความเข้าใจกับลูกค้าของคุณ ดูว่าคุณสามารถแมปทั้งแคมเปญของคุณในที่เดียวได้อย่างไร ดูวิธีที่คุณสามารถปรับปรุงกระบวนการสำหรับการเปิดตัวที่มีผลกระทบ

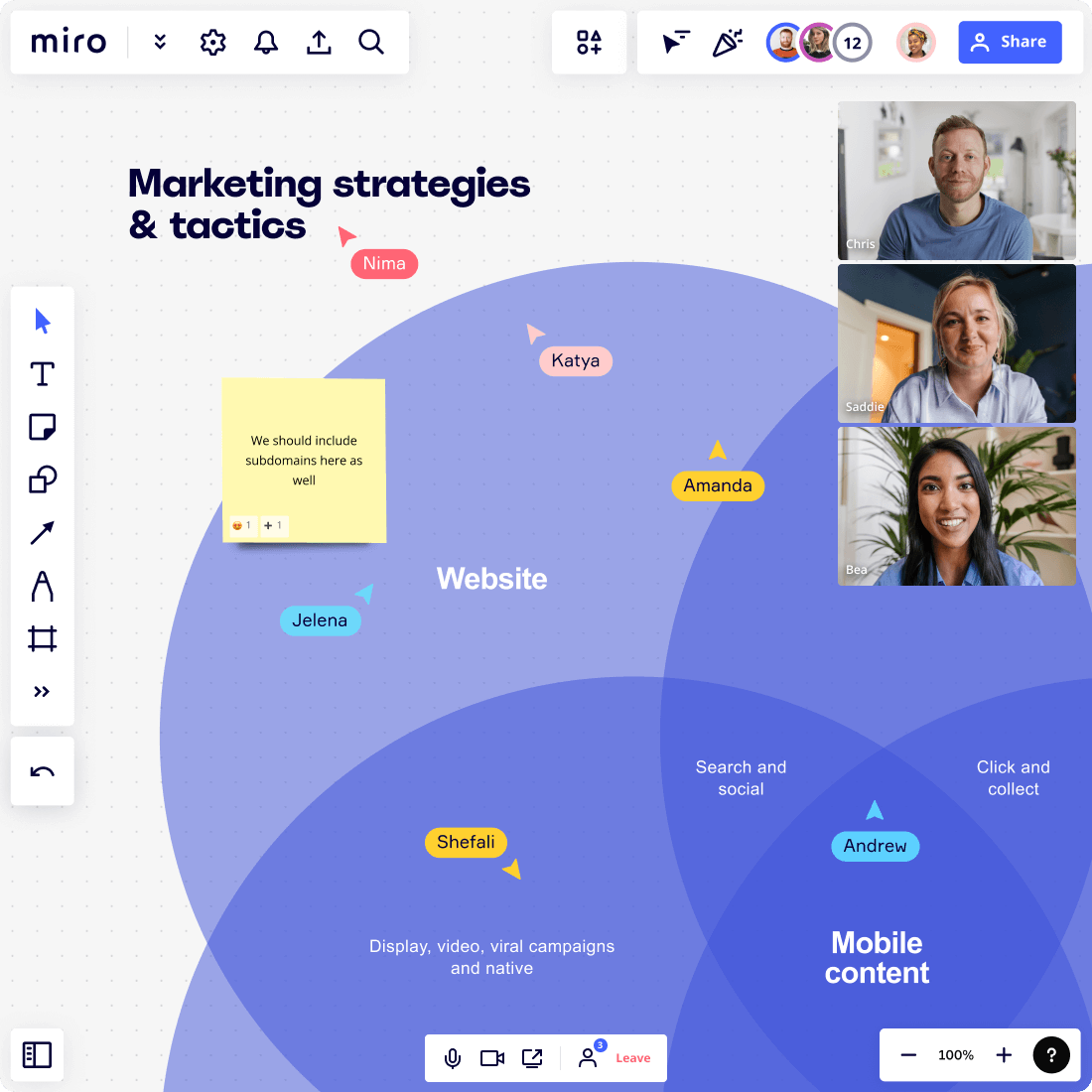

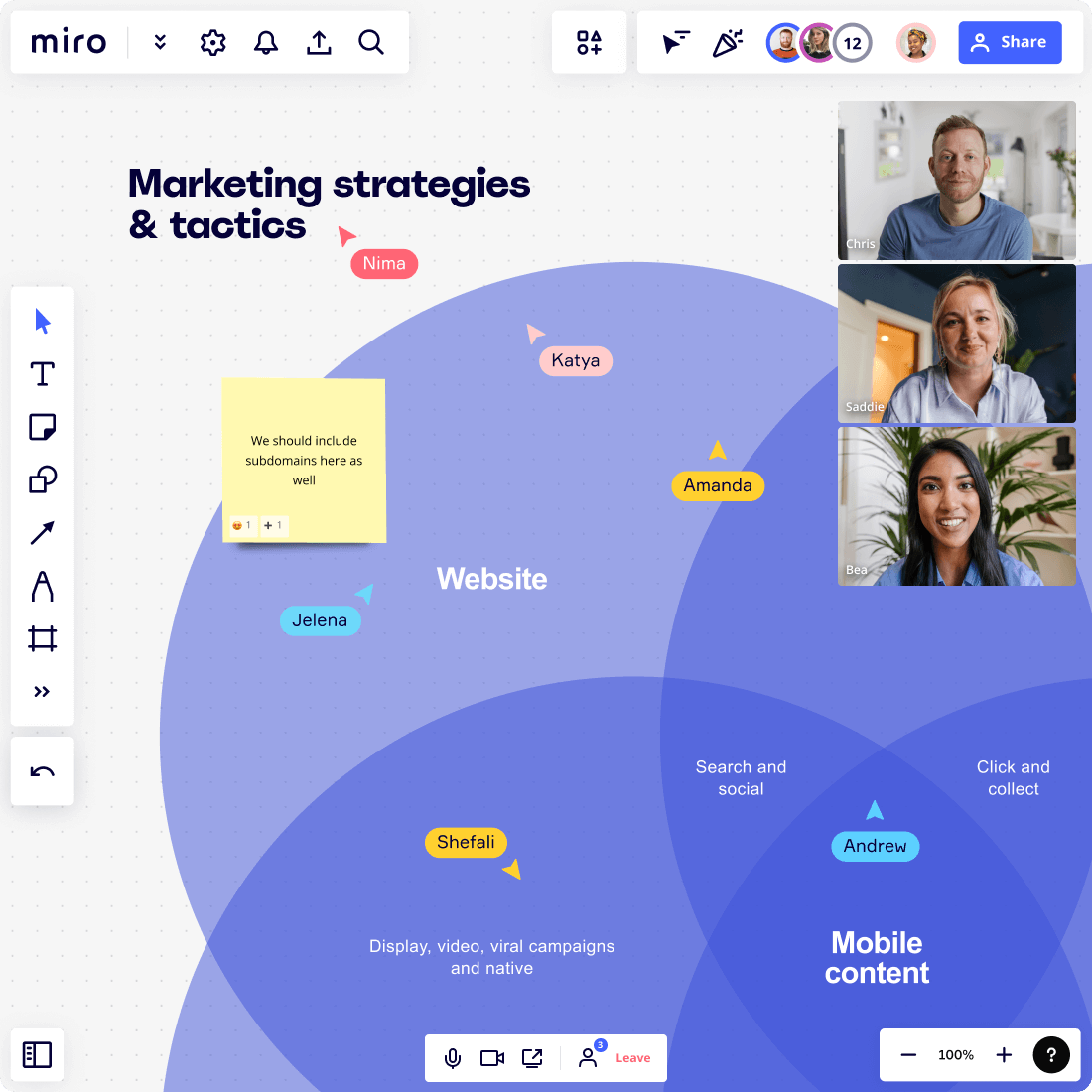

ไม่เคยละสายตาจากลูกค้า จัดทีมในการแก้ปัญหาความต้องการที่จะส่งผลกระทบต่อธุรกิจอย่างแท้จริง เมื่อคุณสร้างแผนที่ภาพเส้นทางแบบโต้ตอบและเป็นภาพร่วมกันใน Miro

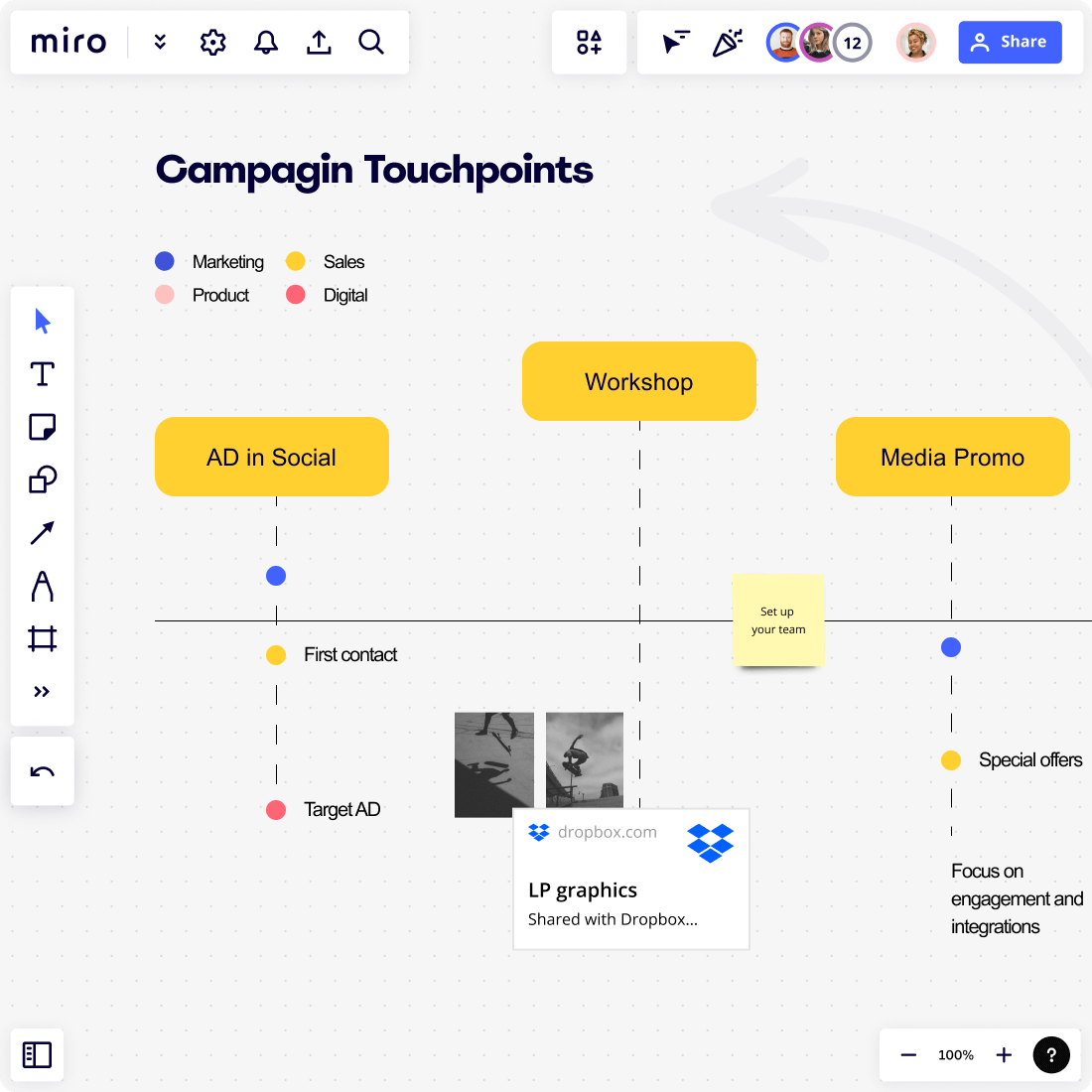

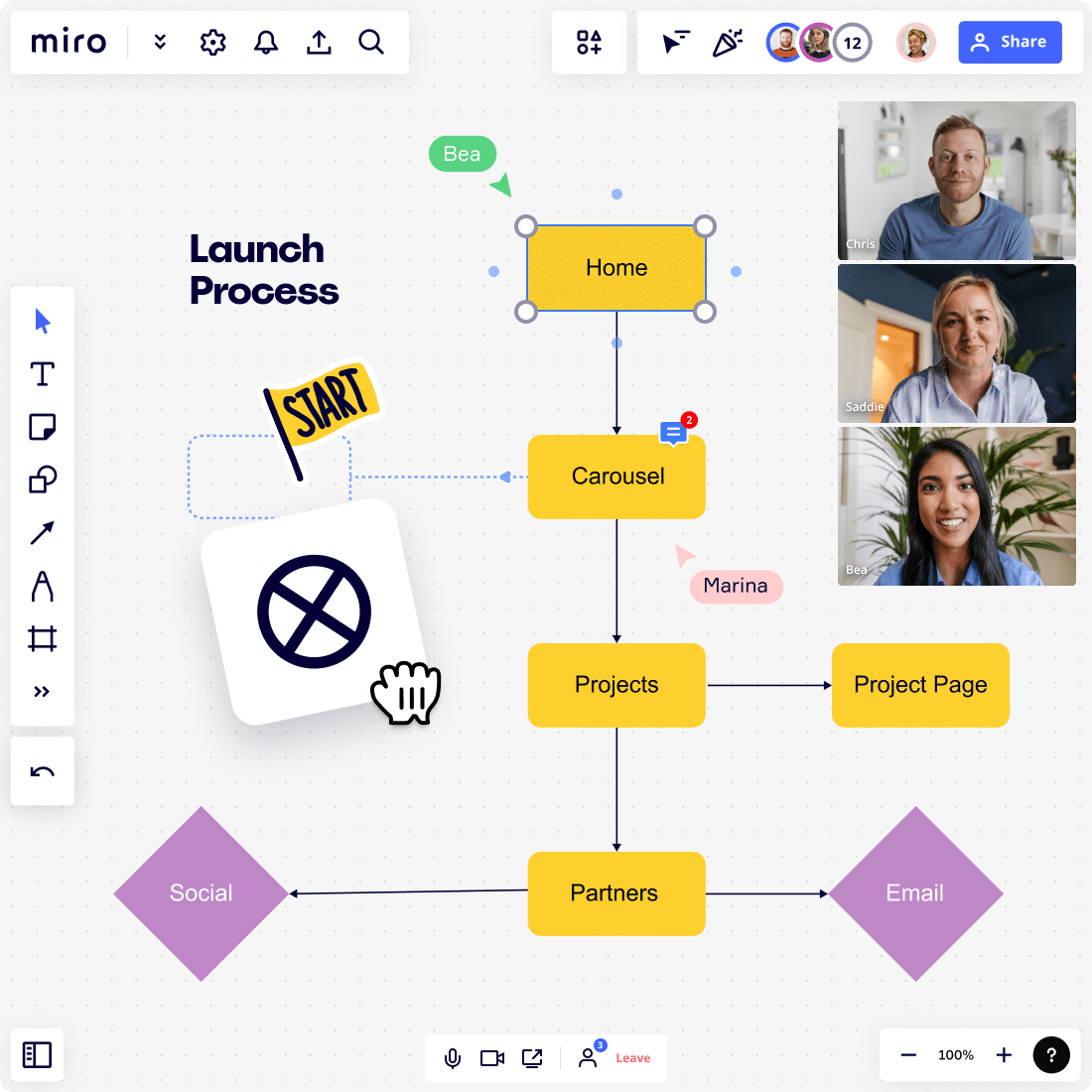

รับแนวคิดที่ยอดเยี่ยมจากหัวของทีมของคุณและเข้าสู่กระดาน ซึ่งพวกเขาสามารถกลายเป็นจริงได้ด้วยวิธีการที่สร้างสรรค์ ระดมสมอง ค้นคว้า และทำแผนที่ได้อย่างง่ายดายแม้แต่แคมเปญที่ซับซ้อนที่สุดบนผืนผ้าใบภาพที่ใช้งานง่ายของ Miro

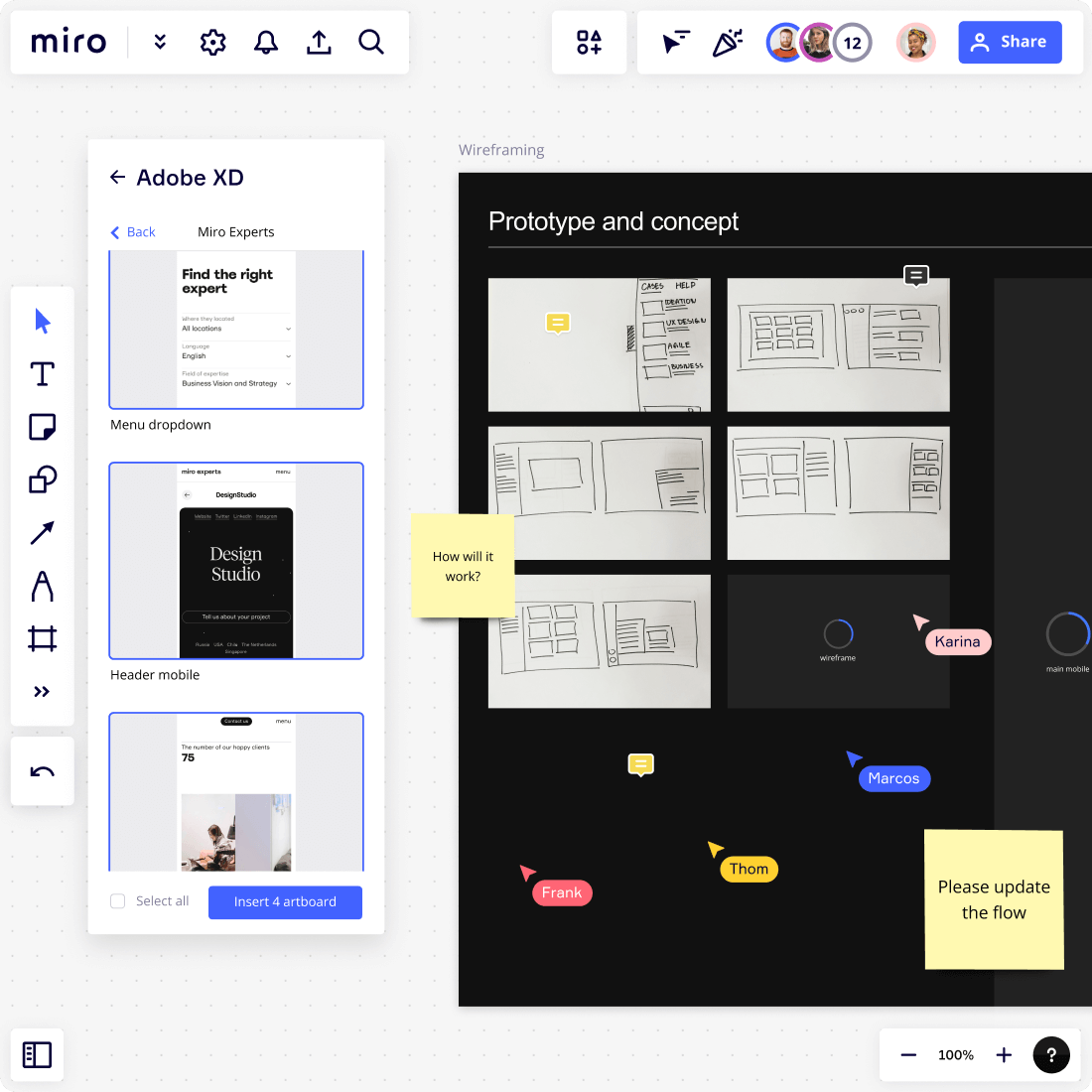

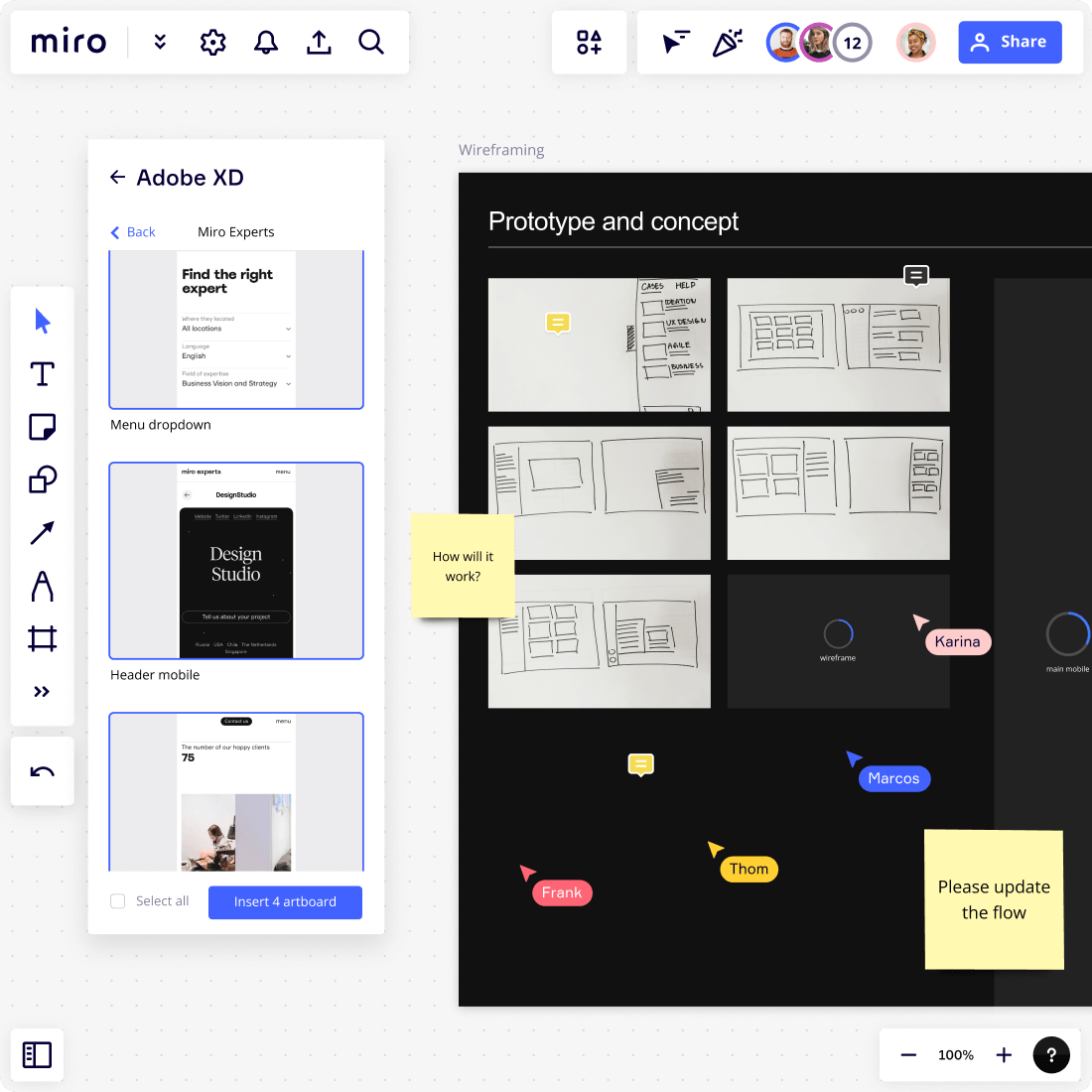

ทำลายไซโลที่นำไปสู่ประสบการณ์ที่ไม่สอดคล้องกันและกระบวนการที่ไม่สมบูรณ์ วางภาพสเก็ตช์ ไวร์เฟรม รูปภาพ วิดีโอ และอื่น ๆ ได้อย่างง่ายดายเพื่อให้ทุกคนทำงานร่วมกันในที่เดียว

ลดความสับสนและการทำงานที่ช้าลงเมื่อคุณรวมศูนย์การวิจัยเพื่อเปิดตัว สินทรัพย์ และแผนบนบอร์ดที่ใช้ร่วมกัน ด้วยแหล่งข้อมูลจุดเดียว ทำให้คุณและทีมของคุณสามารถทำงานร่วมกัน สร้างนวัตกรรม และก้าวนำหน้าตลาดได้

ทีมงานทุกขนาดกำลังสร้างนวัตกรรมและดำเนินการได้เร็วกว่าที่เคย ด้วยการป้องกันระดับองค์กร 99% ของบริษัทที่อยู่ใน Fortune 100 ไว้วางใจ Miro

เชื่อมต่อเครื่องมือของคุณและปิดแท็บของคุณด้วยแอปที่คุณใช้และชื่นชอบอยู่แล้ว

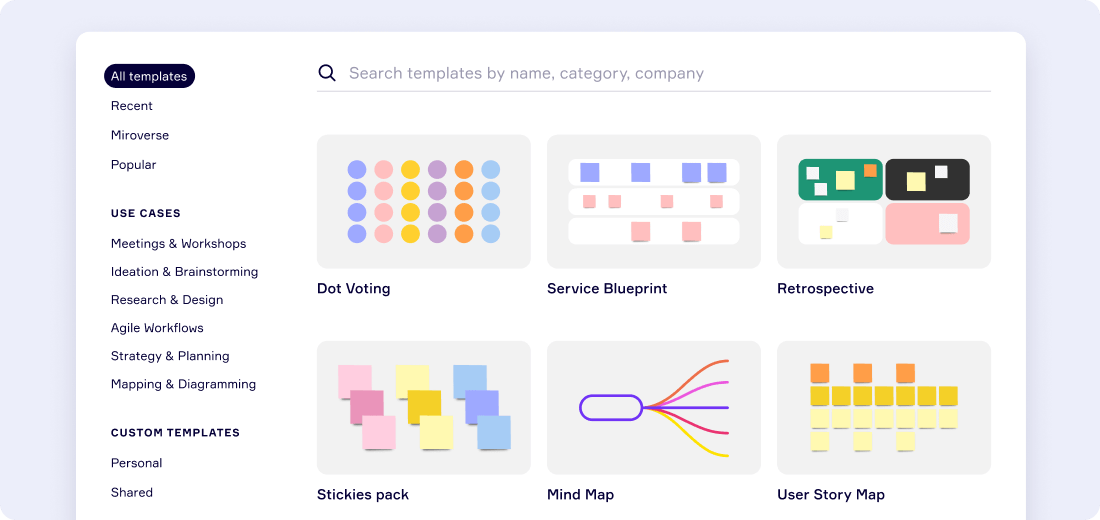

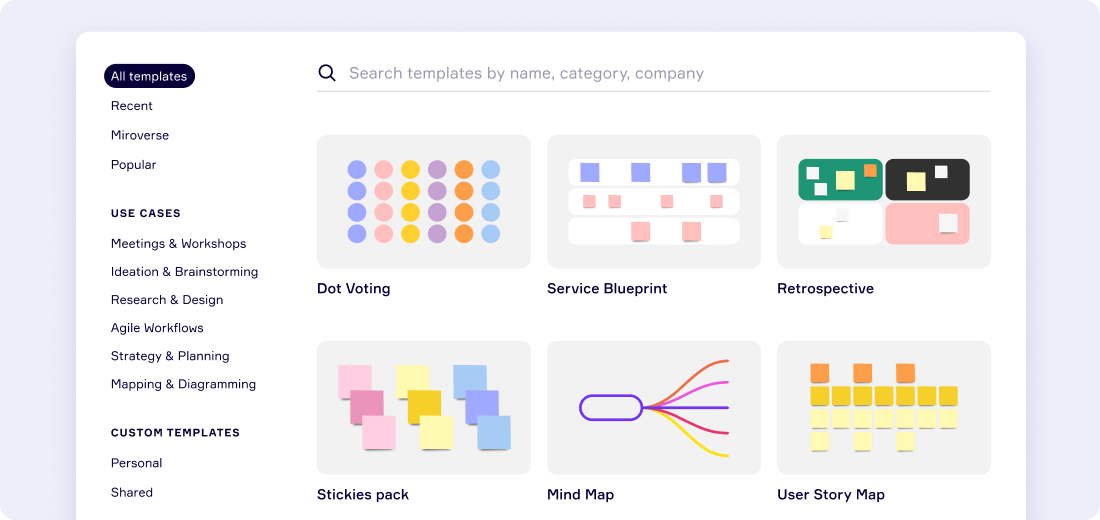

ประหยัดเวลาด้วยเฟรมเวิร์กสำเร็จรูปและเวิร์กโฟลว์ที่ผ่านการพิสูจน์แล้ว

เข้าร่วมทีมงานนับพันโดยใช้ Miro เพื่อทำงานให้ดีที่สุด

ประสานการทำงานร่วมกับทีมของคุณภายในไม่กี่นาที