October 14

Nu kan du registrera dig för årets största Miro-evenemang – Canvas 25! Registrera dig nu och säkra din plats den 14 oktober

REGISTRERA DIG NU

NYC or Virtual

Nu kan du registrera dig för årets största Miro-evenemang – Canvas 25! Registrera dig nu och säkra din plats den 14 oktober

REGISTRERA DIG NU

Nu kan du registrera dig för årets största Miro-evenemang – Canvas 25! Registrera dig nu och säkra din plats den 14 oktober

REGISTRERA DIG NU

Nu kan du registrera dig för årets största Miro-evenemang – Canvas 25! Registrera dig nu och säkra din plats den 14 oktober

REGISTRERA DIG NU

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

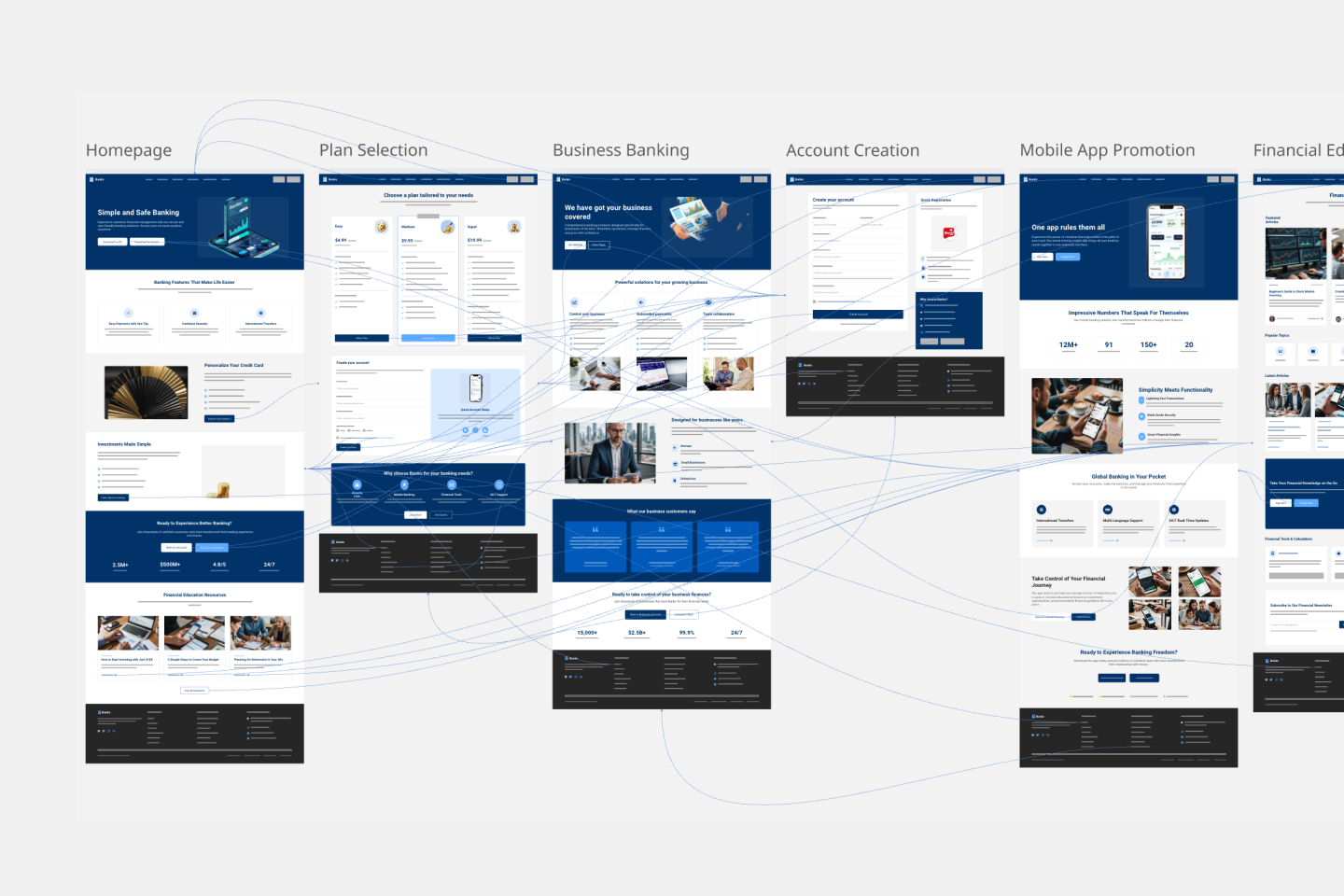

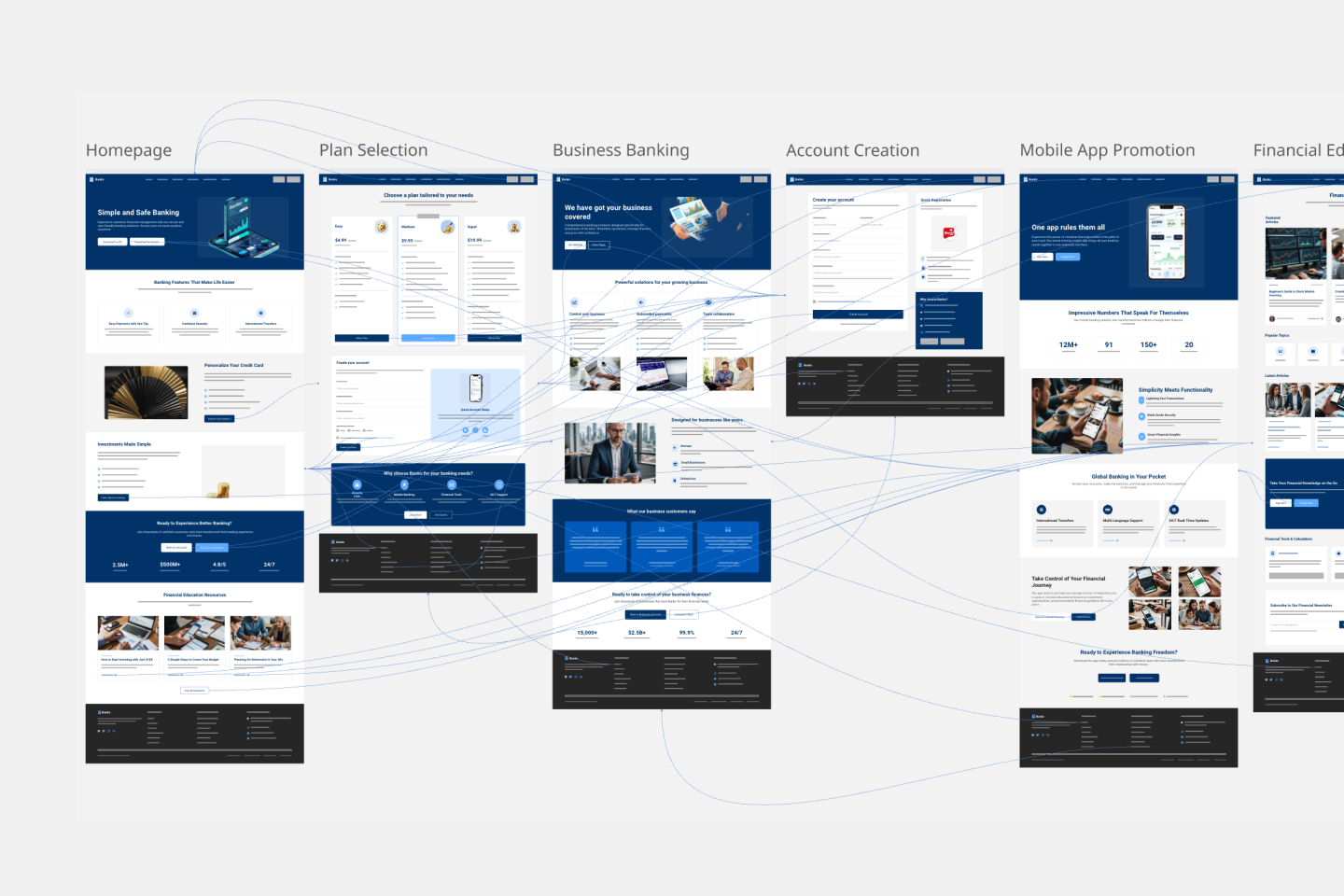

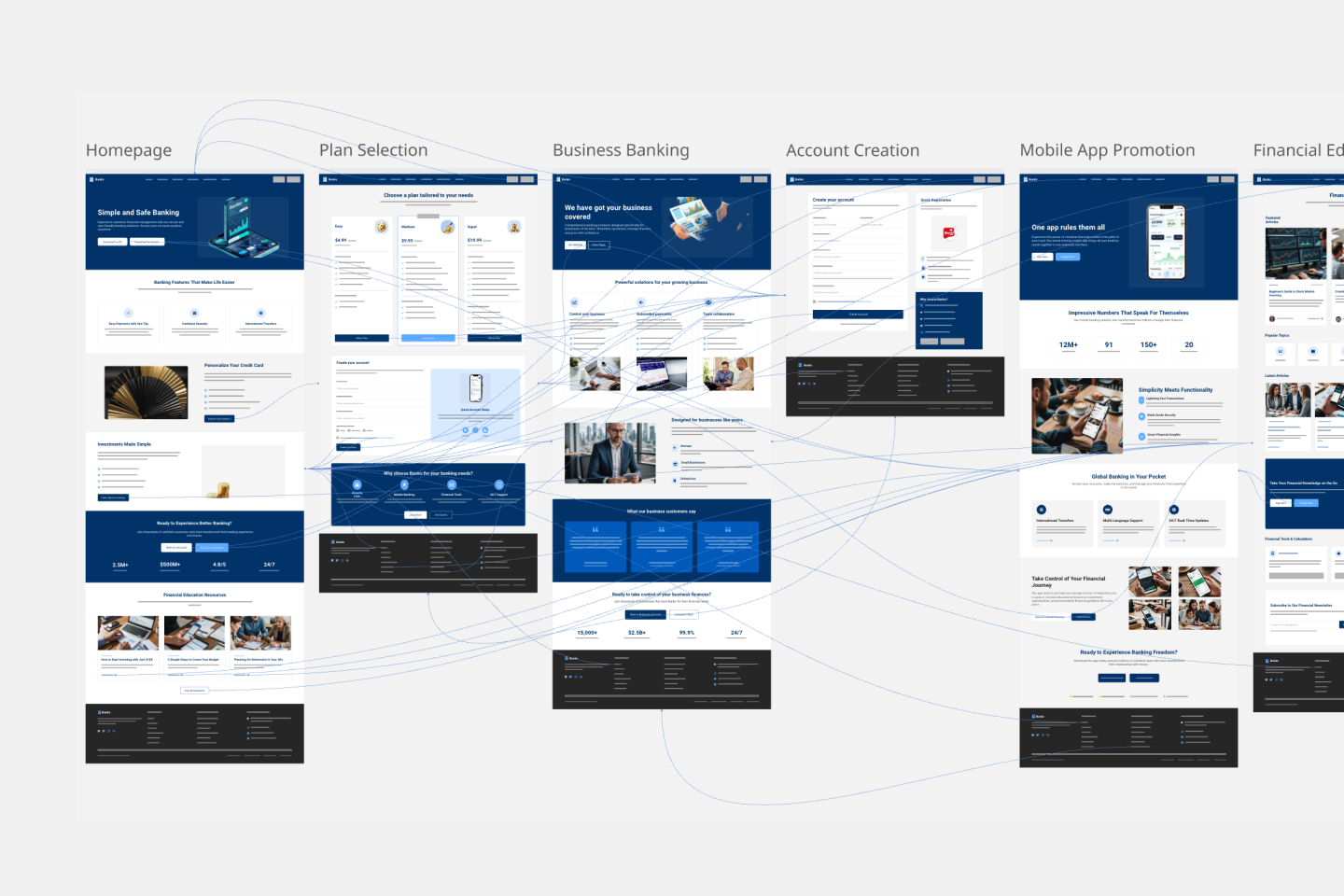

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

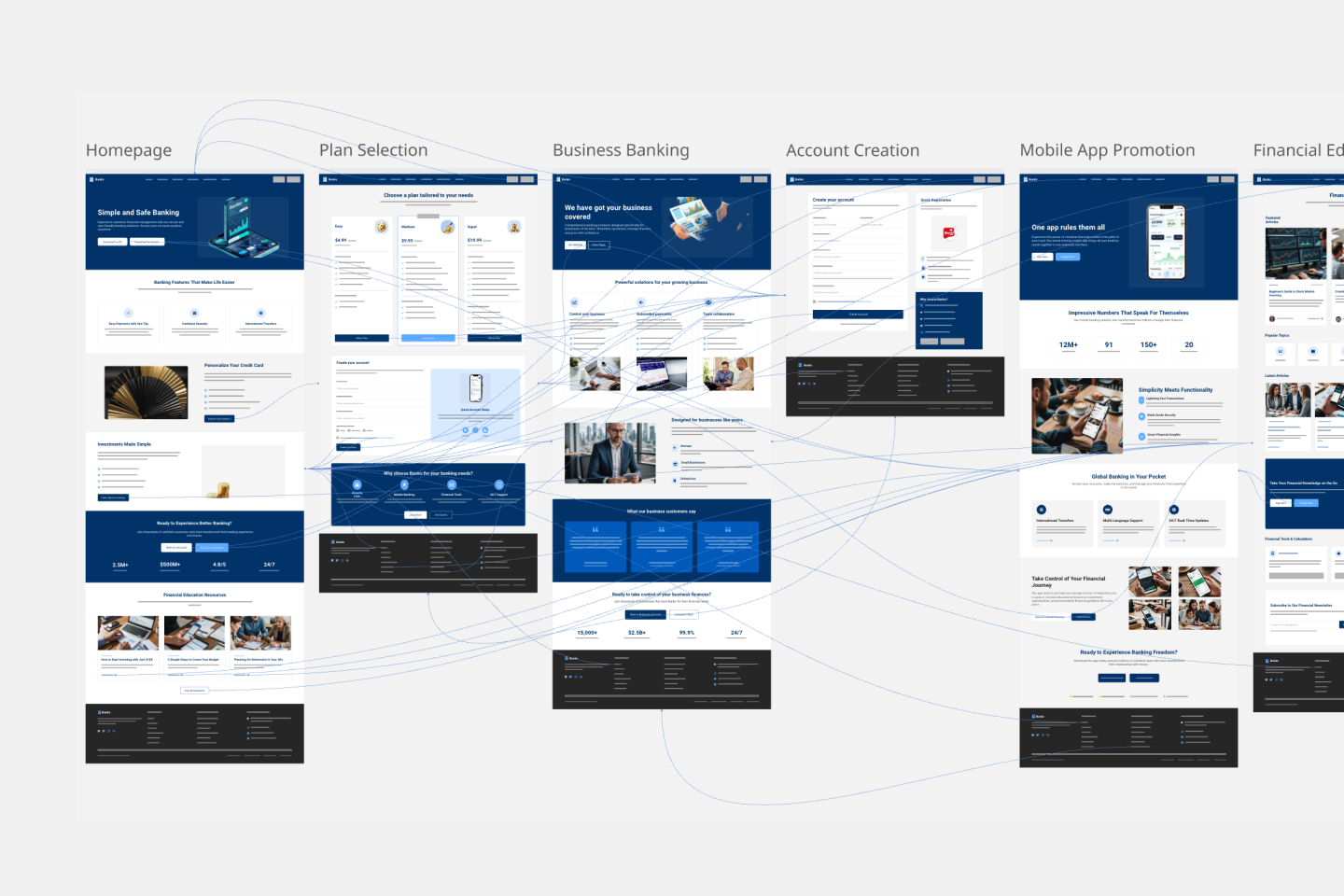

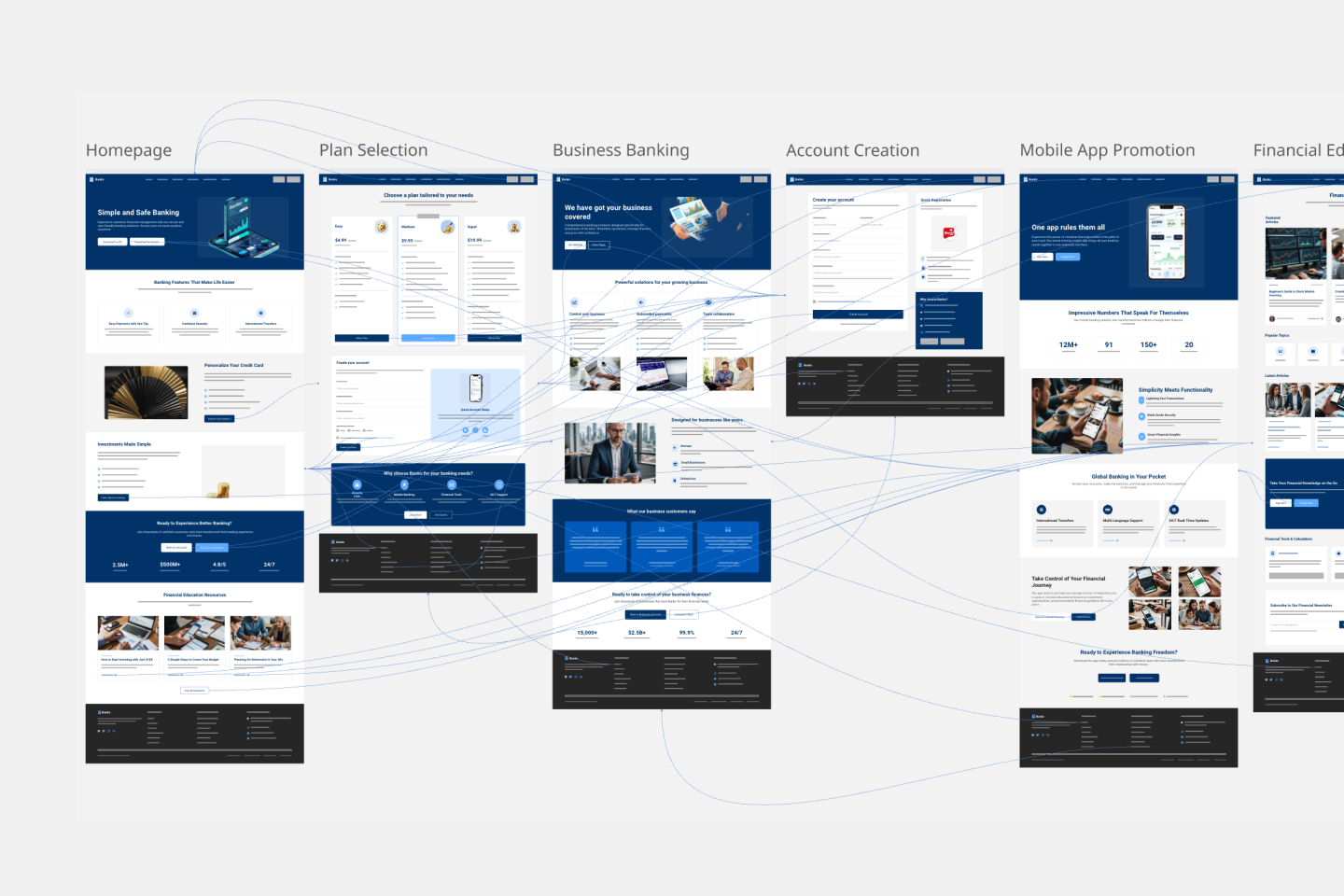

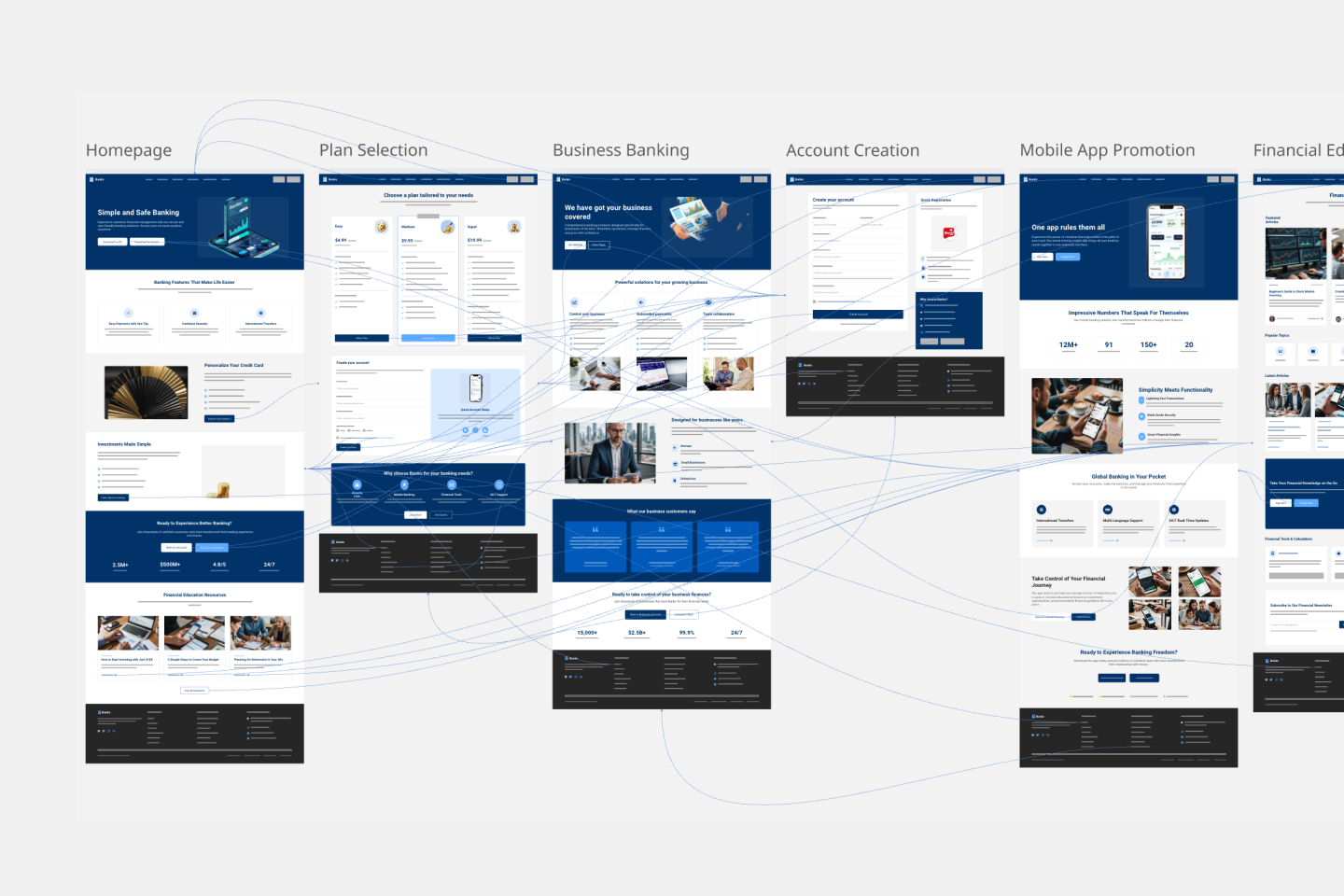

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

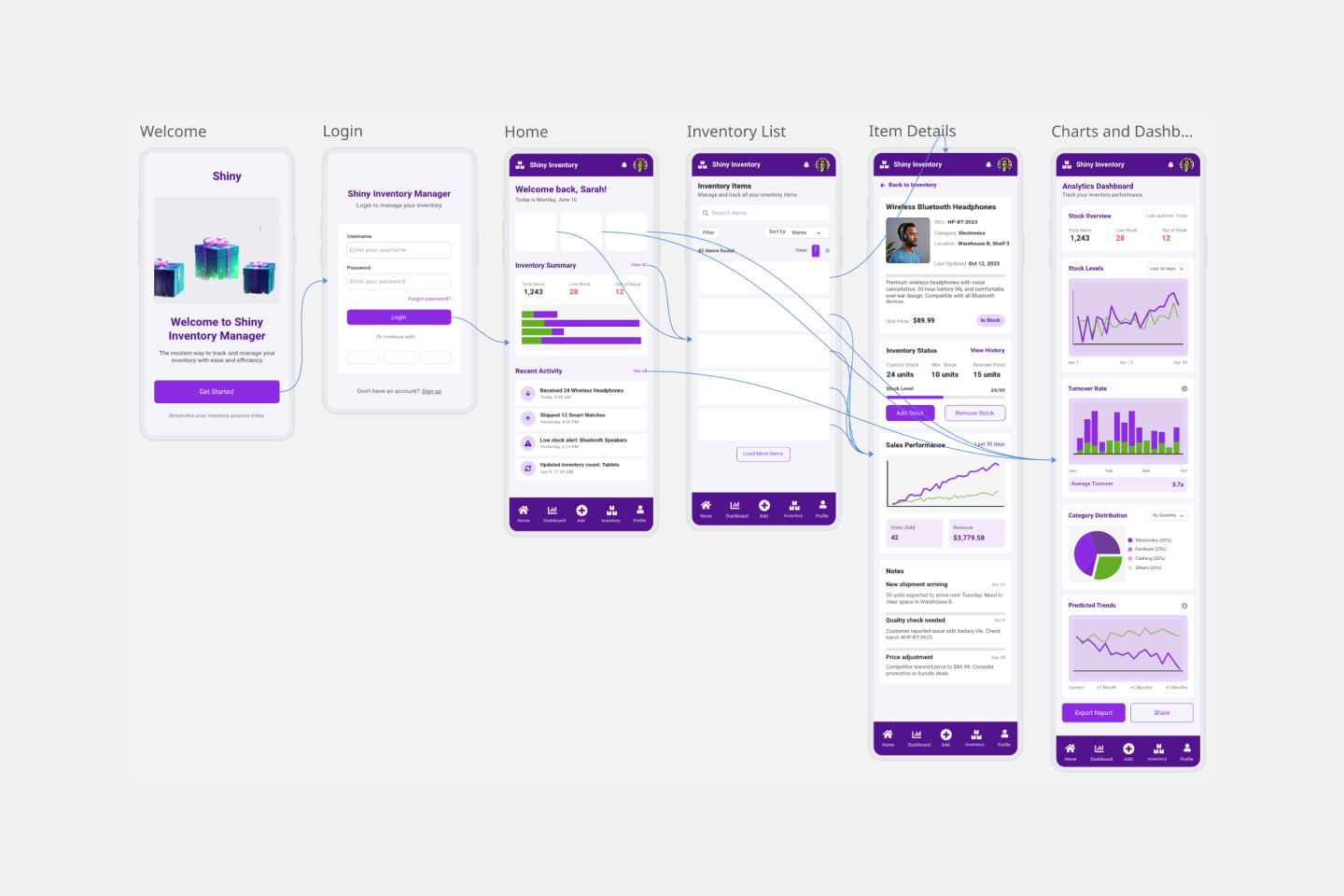

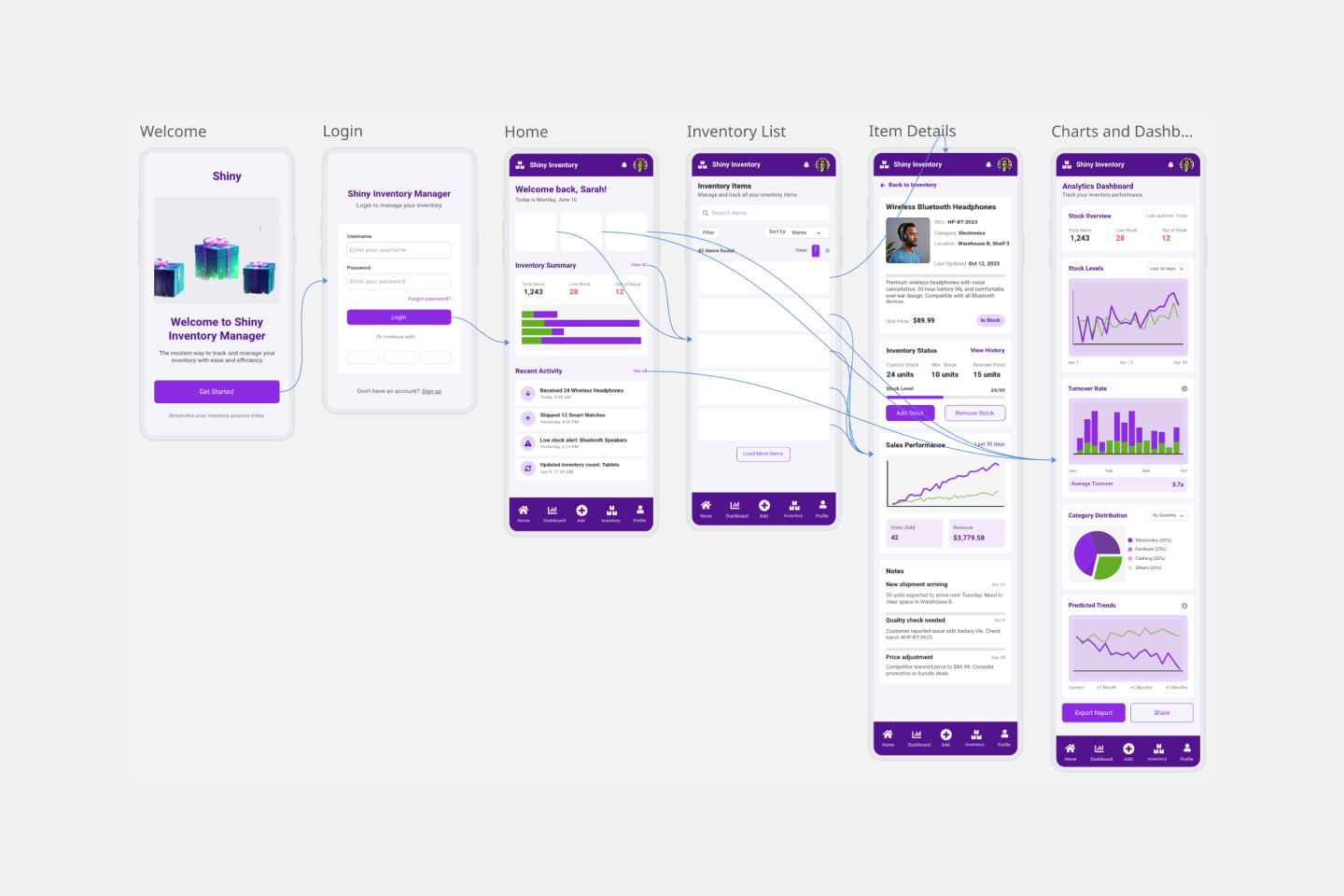

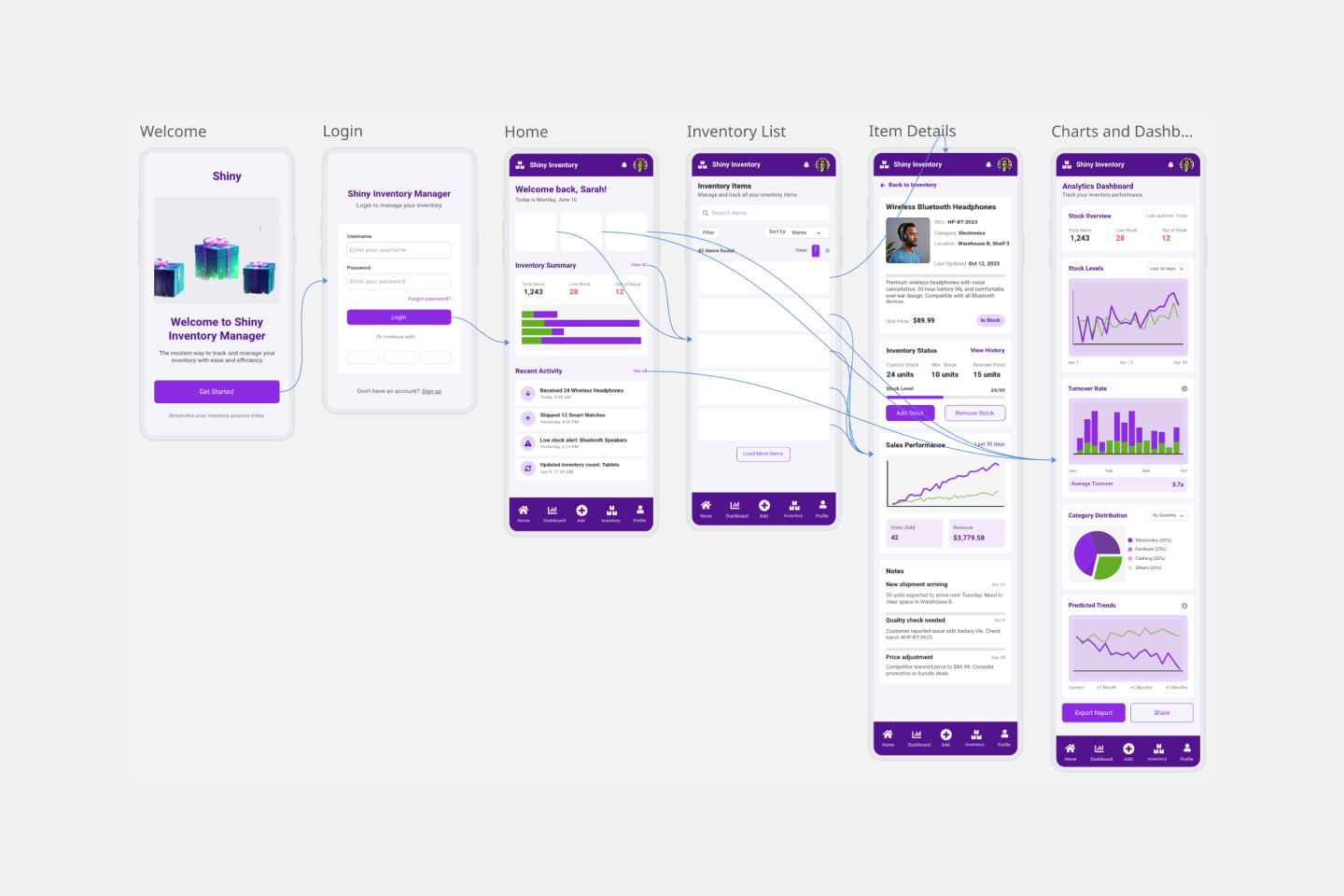

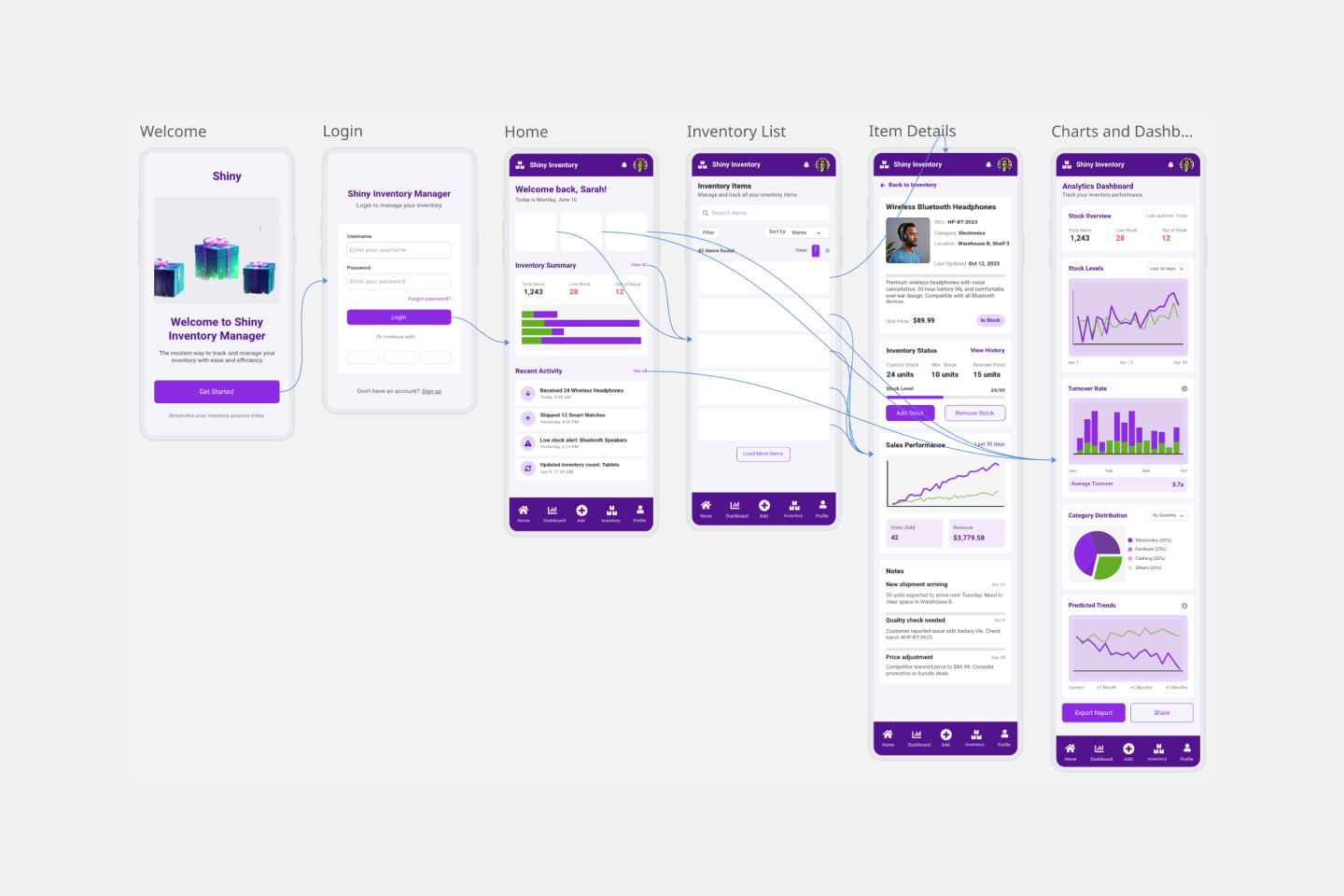

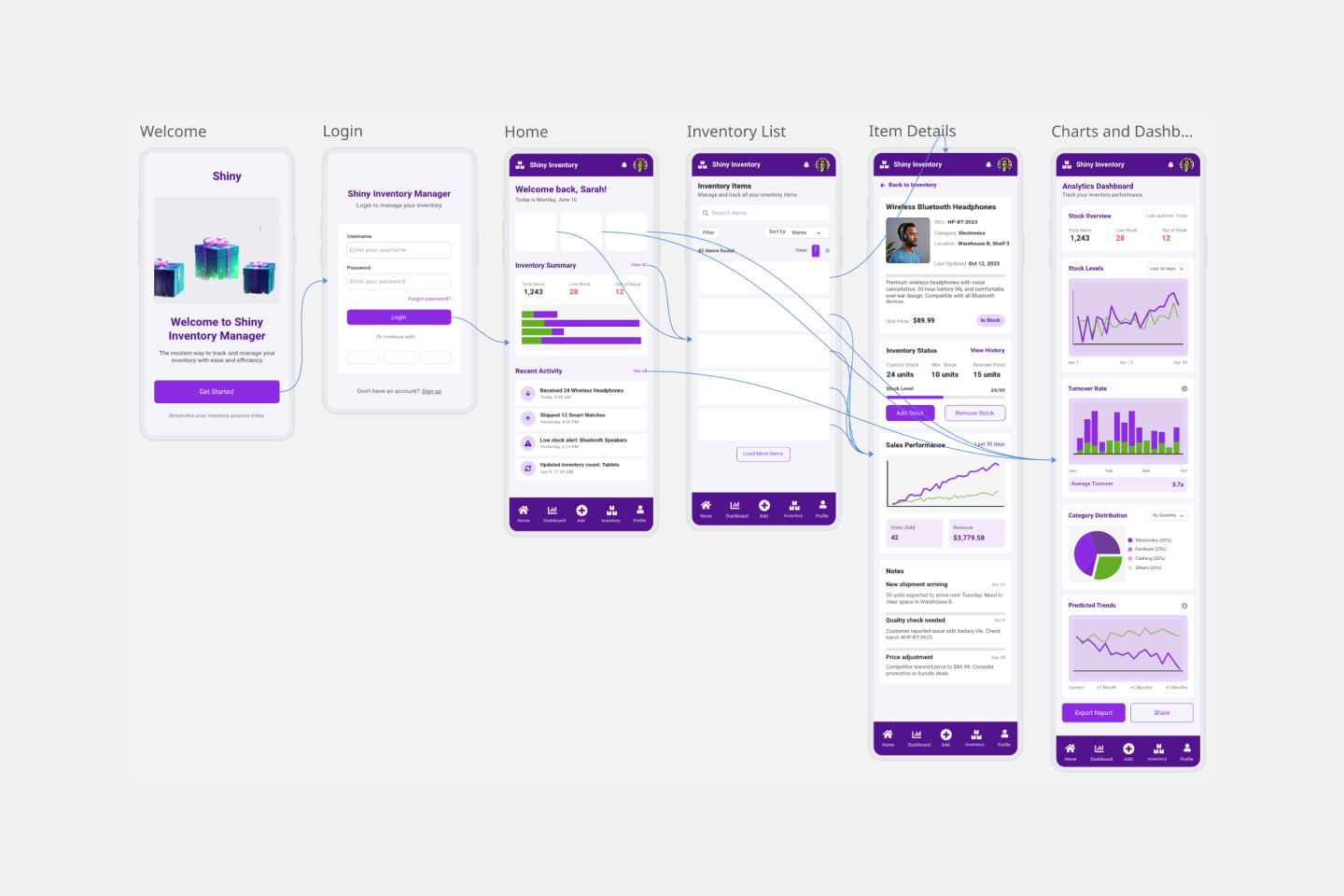

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

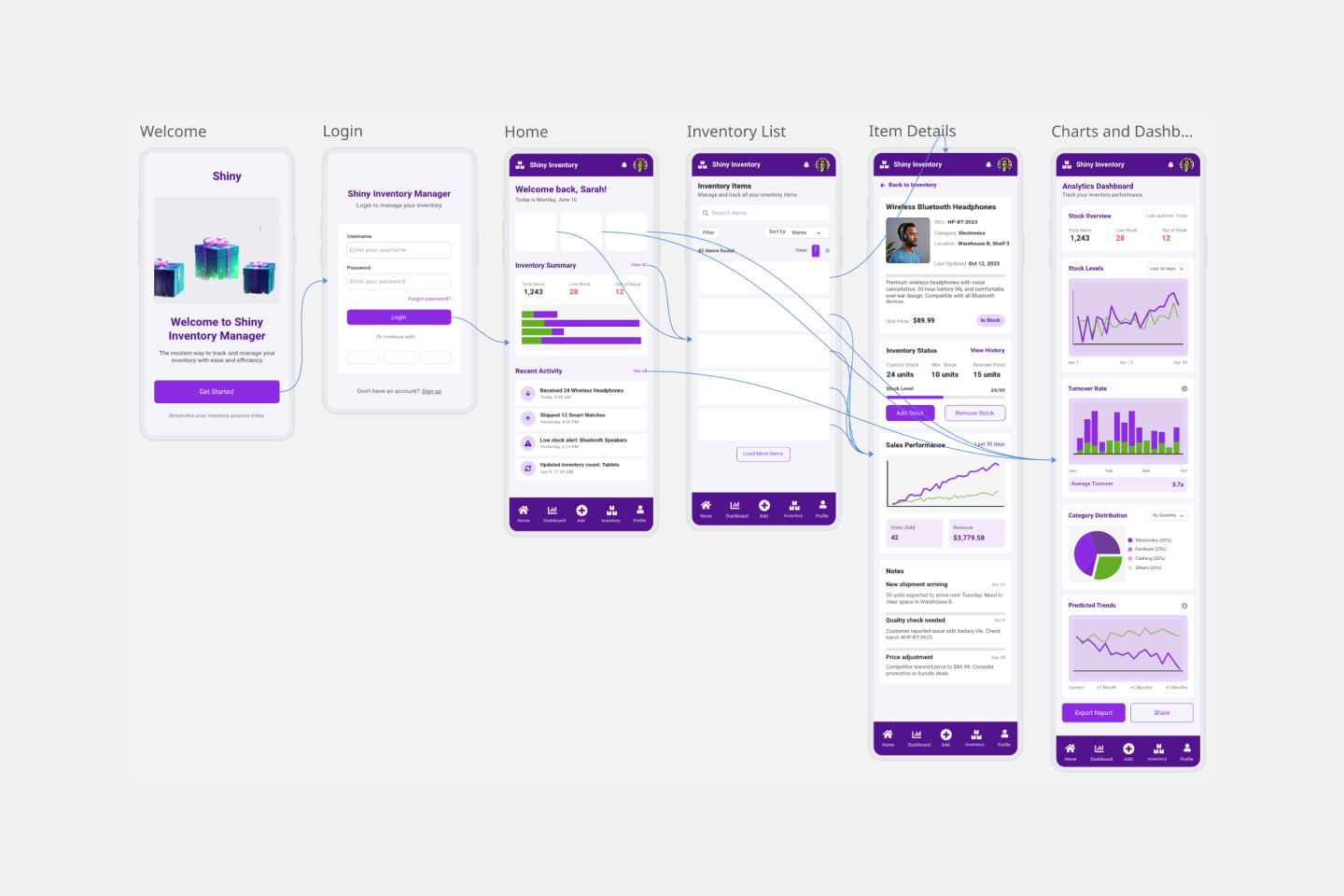

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Begränsad tillgänglighet

AI-prototyper med samarbetsprägel

Gör om röriga idéer och strukturerad forskning till redigerbara prototyper i proffsklass på några minuter. Utforska fler möjliga riktningar, iterera snabbare och kom överens om bättre lösningar innan ni går vidare till verktygsutformning eller kodning.

Mer än 90 miljoner användare och 250 000 företag samarbetar på arbetsytan för innovation

Varför ska jag välja Miro för prototyper?

Utforska fler idéer och förbättra dem enkelt

Kom överens om strategin så att teamet kan fatta beslut snabbare

Fånga kundernas intresse med visuella element för att få snabbare engagemang

Så fungerar det

Konvertera befintligt innehåll på kanvasen till prototyper på några minuter. Miro Prototyper är utformat för snabbt, flexibelt samarbete – oavsett om ni utforskar funktioner eller håller en workshop.

Skapa med AI

Använd AI för att generera flerskärmsprototyper från fästisar, skärmbilder, diagram eller prompter.

Börja med en skärmbild

Ladda upp skärmbilder av appar eller webbplatser och omvandla dem till modeller. Inga designfiler behövs.

AI-driven redigering

Finjustera och remixa med AI. Växla mellan varianter, justera layouter och välj den version som fungerar bäst.

Förhandsgranska och klicka igenom

Ge flöden liv med klickbara prototyper och guidade hotspots – perfekt för delning, testning och snabb feedback.

Utforma med varumärkestillgångar

Ladda upp en varumärkestillgång för att tillämpa dina färger, så att prototyperna känns mer verkliga med mindre arbetsinsats.

Redigera med dra-och-släpp

Anpassa skärmar med hjälp av redigerbara komponenter som är utformade för produktflöden.

Populärt bland produktteam

Testa de populäraste mallarna som passar ditt team

Du behöver aldrig börja från noll. Dra nytta av Miros stora bibliotek med anpassade mallar, som skapats för vardagens arbetsflöden.

Create product prototypes, conduct usability testing, and gather stakeholder feedback.

21000b3c-2496-4e73-bc94-b59192206517

Visualize and iterate website designs using the latest AI capabilities for improved prototyping. Start off with our website prototype template.

95e82821-80c4-40d9-a78e-3c6eb1e720bc

Streamline the creation and refinement of mobile app designs with the mobile app prototype template. Have a structured yet flexible framework that allows teams to quickly sketch, iterate, and perfect their app concepts.

78622b37-d691-4abd-a069-fbe4f3bade83

Map out your website elements, bring your vision to life, and create a better user experience.

bd2d2960-f2dd-4ca8-84a2-32d765faf126

Create the best version of your website or app prototype and get feedback early on.

3251bfb5-7a86-4987-aa30-75d35272caa8

Behöver du hjälp med att komma igång?

Få tillgång till kostnadsfria kurser för att bemästra kanvasen på nolltid, bläddra igenom vår blogg, få snabba svar från vårt hjälpcenter och mycket mer.

Vanliga frågor och svar

Vad är Miro AI Prototyper?

Vem är Miro Prototyper till för?

Vad kan jag skapa med det?

Hur skiljer sig detta från verktyg såsom Figma?

Hur skiljer sig detta från vibe-kodningsverktyg?

Kan jag använda Miro Prototyper utan att aktivera Miro AI?

Används mina data för att träna era AI-modeller?

Hur fungerar priserna?

Är Miro Prototyper tillgängligt för Enterprise-planer?

Produkt

Lösningar

Resurser

Företag

Planer och priser

Produkt

Lösningar

Resurser

Företag

Planer och priser

Produkt

Lösningar

Resurser

Företag

Planer och priser

Produkt

Lösningar

Resurser

Företag

Planer och priser